RESEARCH ARTICLES

Evaluation of the quality of care during labor and childbirth in adolescents

Lílian Machado VilarinhoI; Lidya Tolstenko NogueiraII; Elizabeth Eriko Ishida NagahamaIII

IMaster of Science and Health, Federal University of Piauí, Assistant Professor I of the Higher Education Association of Piauí, Teresina, Piauí, Brazil, email: lilianvilarinho@hotmail.com.

IIPhD in Nursing, Associate Professor, Department of Nursing, Graduate Program in Nursing in Science and Health at the Federal University of Piaui, Teresina, Piauí, Brazil, email: lidyatn@gmail.com.

IIIPhd in Public Health, State University of Campinas, Nurse at the Regional University Hospital of Maringa, State University of Londrina, Maringa, Parana, Brazil, email: eeinagahama@uem.br.

ABSTRACT: Evaluative research aimed to evaluate the quality of care during labor and live births to teenagers in a health institution in Teresina, Piauí, Brazil and identify factors associated with quality of care. There wer174 medical records analyzed and 44 teenagers interviewed from May to July 2010. Based on recommendations from the Ministry of Health, indicators related to the care process were selected. The quality of care was categorized as more appropriate, adequate, intermediate and inadequate. Univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics were used, adopting a significance level of 5%. It was found that labor and delivery care was adequate for 26.7% of teenagers. It was found that, teenagers which had less than six prenatal consultations or a history of cesarean delivery care received intermediate or inadequate birth care. There is a need to improve the quality and humanization of care during labor and in the process of parturition.

Keywords: Health evaluation; adolescent; labor obstetric; parturition

INTRODUCTION

Teenage pregnancy worries the various sectors of society, because about 14 million teenagers 15-19 years of age become mothers every year, totaling more than 10% of births in the world. Although these births occur in society as a whole, more than 90% occur in developing countries, and the African continent that has the highest rate of pregnant teenagers1.

In Brazil, the number of births in teenagers, according to data from the Ministry of Health, has fallen 30% from 2000 to 2009 in all the national territory and the largest reduction occurred in the Northeast Region (26%). In the State of Piaui, the reduction of births for mothers in this age group, which are registered by the Unified Health System (SUS) and carried out in the public network, reached 28.7%2.

Despite this reduction, in 2009 there were over 400 thousand births in teenagers throughout the country2. Therefore poses a challenge to health services and care for the pregnant teenager parturient and providing quality care, based on the philosophical principles of holistic care3.

Constructing a holistic view on the health/disease process, establishing new bases for the relationship of the various individuals involved in the production of health - professionals, users and managers - and establish a culture of respect for human rights, among which are included the reproductive rights4, constitute the bases for the qualification of care.

This study aimed to evaluate the quality of care during labor and delivery of teenagers who had a child in a health institution of a municipal public network in Teresina, Piauí, Brazil and identify factors associated with the quality of care.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Over the centuries, a predominant social model was built that prevents women from being subject to their own history. In this context, historical and social determinants are reflected in issues related to women's health, such as the exaltation of motherhood2 .

For a long time the experiences of childbirth were in different cultures a tradition unique among women, and the birth was considered a natural and human event, in which the woman was the protagonist5. The delivery was performed in the household only by midwives, women who devoted themselves to assist the woman in giving birth, because they were knowledgeable about the pregnancy and puerperium from their own experience. Later, for psychological and humanitarian reasons, women would prefer that their deliveries were performed by midwives5.6.

However, the midwife profession suffered a decline, especially, because of the discussions in the public sphere about the maternal and perinatal mortality, the assertion of obstetrics as a discipline dominated by technical and scientific man, who went on to develop actions to discipline and control the birth, through the use of forceps and cesarean define as the best option for the birth. Thereafter, childbirth ceases to be private, intimate and feminine and becomes characterized as a medical event, with the presence of other social actors7.8.

Thus, the medicalization of the female body and the institutionalization of medical delivery make the birth a mechanical process and each step of the delivery time and space sorted, with a view to efficiency and speed of service, not taking into account the individuality and autonomy of women. Therefore, the institutional interests and medical knowledge overlap the needs of the women9,10.

Regarding attention to labor and birth, the Health Ministry emphasizes that the current dominant model is dependent on medical technology, which reduces confidence in women's innate ability to give birth without intervention5. Such valorization of technological interventions, both by pregnant women as by professionals, comes hiding an indiscriminate medicalization, removing the woman from the leading role of childbirth11.

Regarding the public policies for delivery care, stands out in the international context: the realization, on the part of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Europe and the Americas conferences on appropriate technology to assist labor and birth. As a result of these meetings was drawn up a document that provides recommendations on practices related to normal delivery, such as the abolition of the routine use of various obstetrical practices, considered inadequate and harmful assistance at birth12.

Even with the international movement of labor and childbirth humanization since the 80s, some maternity units continue adopting procedures considered to be harmful, such as: the ban on feeding during labor, the realization of trichotomy and episiotomy, the imposition of the litotomica position, in addition of non-acceptance of the presence of a companion during the delivery process. There is notoriously strong institutional resistance to change and insistence hospitals and public hospitals in providing assistance based on the interventionist obstetric model, making childbirth lonely, painful and suffering, particularly for young people and teens in their first experience of motherhood10.

In this sense, the childbirth fear acquires a peculiar significance among pregnant teenagers, linking their immaturity to a supposed biological inability to childbirth, culminated with the fear of dying. Thus, during pregnancy, the ideal is that teens have group meetings to discuss the fears, anxieties, fantasies and myths about childbirth, as well as answering questions relating to the newborn care13.

METHODOLOGY:

This is an evaluative research, with a quantitative approach and focus on the assessment of the care process for the teenager during labor and childbirth. The study was conducted in a health institution, belonging to the East-Southeast Region of Teresina, with a resident population of 814,439 inhabitants. Is the city's most populous region, considered as the healthcare hub by the diversity and quantity of services that it offers to the public and private network14.

To calculate the sample, it was considered the number of SUS deliveries occurring in that institution, in 2008, according to the National System of Live Births (SINASC). A total of 1,047 cases were obtained, which corresponded to 7.5% of births in the city of Teresina in 2008. The consultation of the studied unit's information system allowed the survey of 239 live births by teenagers.

Included in the study were the pregnant teenagers, residents in Teresina, who were receiving prenatal care in the health units of this municipality and whose delivery was carried out at the maternity unit of the health facility in the study, in the year 2008. Exclusions from other municipalities (26) and whose records had no record of accomplishment of prenatal care or had not received prenatal care (38). The data were obtained through the analysis of 174 medical records and interviews with 44 teenagers (25.3% of these medical records), during a home visit.

Two instruments with closed-ended questions were applied between the months of March to July of 2010. The first was used for data collection concerning labor and birth care in the medical records and the second, used for the interview encompassed additional information about the care received during labor and childbirth.

The variables of the study were: obstetric examination on admission, type of delivery, use of partograph, conducting Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) at the time of hospitalization, presence of a companion, analgesia at the time that precedes the delivery, complications in childbirth and the professional who performed the delivery.

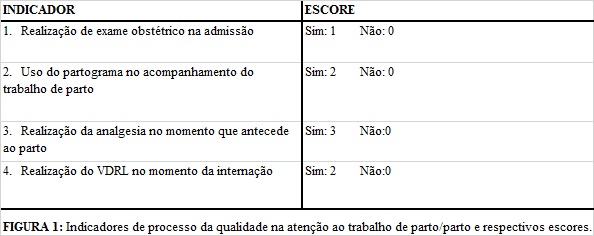

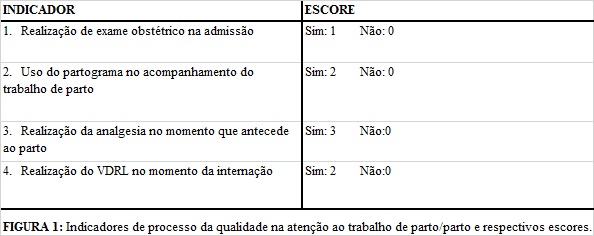

To evaluate the quality of care in labor and birth, four indicators were selected: completion of the obstetric examination upon admission; use of the flow chart; analgesia at the time preceding delivery; completion of the VDRL test at the time of hospitalization, as can be observed in Figure 1. The selection of indicators was based on a literature review and the recommendations of the Ministry of Health for the appropriate care during labor and delivery15.

The completion of the obstetric examination on admission includes mandatory procedures such as auscultation of fetal heart rate, the measurement of uterine height and the palpation obstetric, being an important indicator of quality of care, makes it possible to confirm the labor diagnosis and evaluate the maternal and fetal risk.

Regarding the use of the flow chart, under the point of view of the technical and scientific quality16 , it constitutes a relevant indicator in care to labor, because the disuse of this instrument points to the poor quality of care with the consequent indication of an unnecessary cesarean.

The analgesia is a right of Brazilian women during labor and, from the point of view of the humanization of care, and an indicator of the quality of care.

Regarding the performance of the VDRL at admission, the recommendation of the United Nations Fund for Children (UNICEF) is that if the test is not performed during the prenatal, must do so in childbirth. However, it is recommended that the maternity units perform the VDRL for 100% of pregnant women at the time of delivery, in order to prevent the vertical transmission of syphilis, a marker of the quality of maternal-fetal health care17.

As a parameter for the care assessment during labor and delivery, has established up a scale of scores ranging from zero to three points, according to adequacy in each indicator of quality of care. Different weights for each of the indicators were assigned, according to the relevance to the specific population under study and the representativeness of the indicator on qualified care during labor and childbirth.

To analyze the quality of care during labor and delivery, all scores were considered and calculated the sum obtained individually on each item, which ranged from a minimum score of zero until maximum score of eight. Therefore, four levels were determined According to the quality rating scales added: inadequate - from 0 to 2 points; intermediate - 3 to 4 points; adequate - 5 to 6 points; above appropriate - 7 to 8 points.

The collected data were entered and analyzed using the computer program Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 18.0. In the statistical analysis, were used univariate and bivariate descriptive techniques to identify factors associated with quality of care during labor and childbirth. The chi-square test (c²) was also used and Fisher's exact test and the level of significance was set at 5%.

The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Federal University of Amazonas, CAAE Protocol No. 0228.0.045.000 -09 and complied with the recommendations of Resolution No. 196/96 of the National Health Council (NHC). The teenagers or their guardians, in the case of minors of 18 years of age, who have agreed to participate in the study and signed a consent form.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reported a greater frequency of pregnancy among teenagers aged 15 to 19 years, 164 (94.3%), who lived in consensual union, 88 (50.6%), with fundamental level of schooling, 103 (59.2%) and whose occupation a homemaker, 41 (23.6%).

As the reproductive history, 121 (69.5 %) teenagers were primiparous, with low percentage of previous cesarean sections, 14 (8.0%) and abortion, 16 (9.8%).

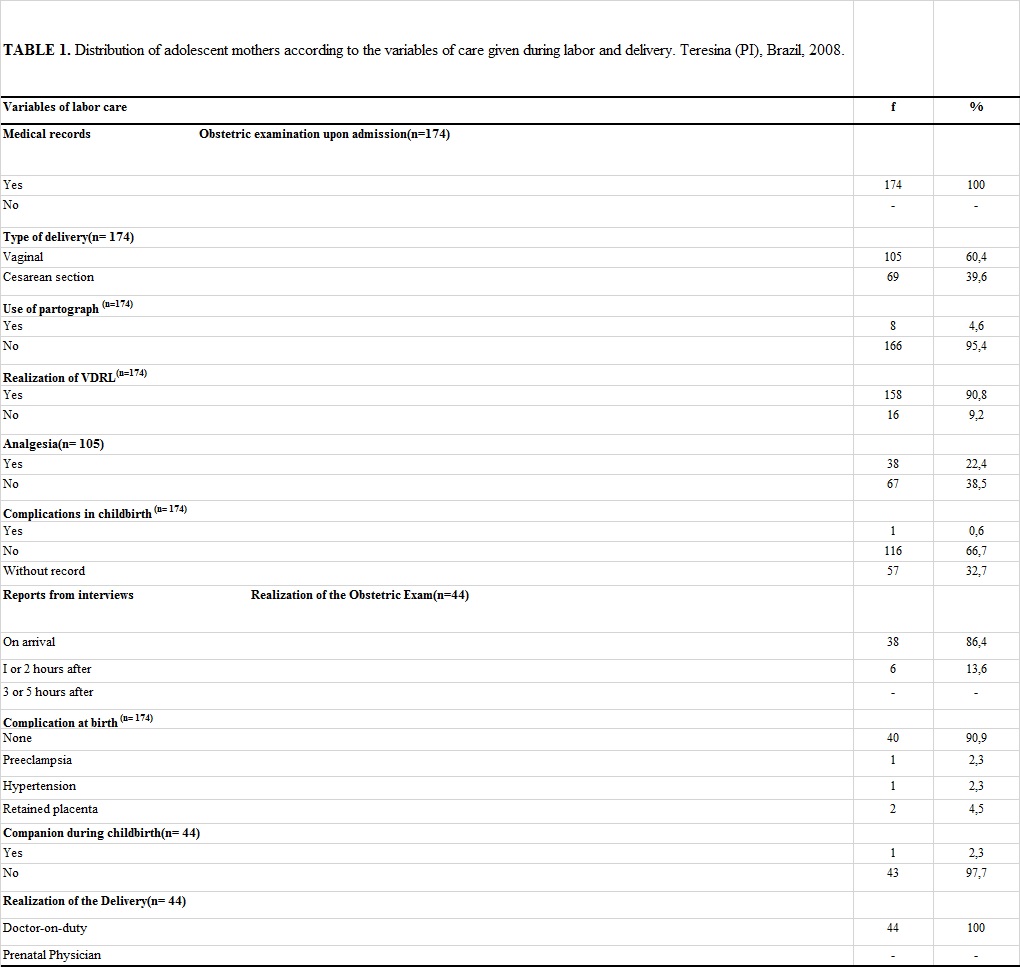

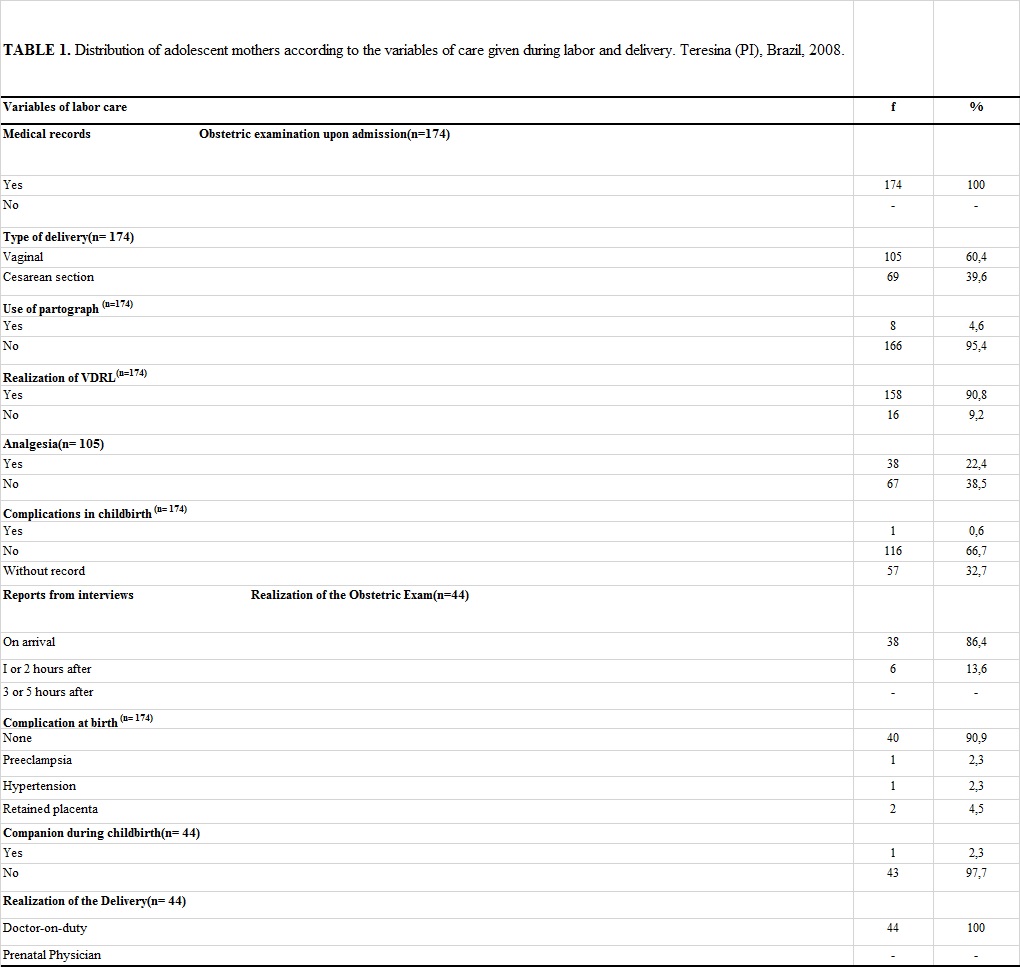

Regarding labor care, all teenagers were examined upon admission to the institution in this study and 38 (86.4%) said they had been attended upon their arrival, which highlights the availability of professionals and responsiveness, as shown in Table 1.

Regarding the type of delivery, 105 (60.4%) had vaginal deliveries and 69 (39.6%), cesarean. The cesarean rate found in this study is worrying, being higher than the recommended by WHO (15%) for cesarean section performed by strictly medical indications18.

A study carried out in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil in 2007, found elevated percentages of cesareans among teenage mothers and affirmed that the cesarean sections should be indicated only in situations of risk, however, are being carried out in uncontrolled manner, without a concern about the risks involved in this surgical procedure19.

Another study compared the delivery of pregnant teenagers and adult women, in Lisbon, Portugal, and identifies smaller proportion of cesarean sections among teenagers than among the adult, 72 (10.6 %) and 1,932 (20.7%), respectively20. In addition to these, other authors have observed that, in the state of Maranhão in Brazil, the number of cesarean deliveries increased with age and that, among the teenagers, the percentages of operative birth were smaller when compared to adult women21.

According to the Ministry of Health, the increase in the number of cesareans is a phenomenon that has been occurring throughout the world, although it has advanced more in the American continent and, specifically, in Brazil, where it is considered epidemic. The arguments used to justify these high rates are the prevalence of pathological processes associated with pregnancy and themselves, to the early or high maternal age and to parity still low or too high5.

Among the reasons that led to the realization of this obstetric procedure by teenagers, stand out cephalo-pelvic disproportion, 24 (30.4%), and cervical dystocia, 14 (17.7%), and some of them had more than one reason for performing the cesarean section. Comparing the findings of this study with another, a similar situation was observed, since these authors, despite finding lower frequency of cephalopelvic disproportion among teenagers than among adults, this was the main indication for cesarean section, followed by pre-eclampsia and malpresentation21 , which were also findings of this study.

It was evidenced that the partograph was used as monitoring the evolution of labor for 8 (4.6%) pregnant women. These data are consistent with a study conducted in Teresina, in which have registered the use of the partograph in only one of the five hospitals studied22. In this sense, this study points out negative aspects related to attention during the evolution of the delivery of teenagers, since WHO recommends the use of the flow chart in maternity wards since 1994, because this instrument can determine the actual need for cesarean sections and allow the monitoring of the evolution of labor and the early diagnosis of dystocia, improving the quality of labor care5.

With regard to the implementation of the VDRL test at the time of hospitalization, it was observed that 158 (90.8%) of the teenagers were submitted to examination, in order to trace the syphilis and prevent the vertical transmission during normal delivery. It is worth pointing out that, even after the completion of the examination by the majority of the teenagers in the prenatal, they collected blood samples to perform the VDRL at the time of admission.

In this sense, the availability of the VDRL test at the time of hospitalization of teenagers was also considered an indicator for the quality of care during childbirth. This examination should be performed for all pregnant women who did not undergo prenatal VDRL, for pregnant women with signs and symptoms of any sexually transmitted disease (STD) during pregnancy, for those whose partners had positive rapid test and pregnant women in the third trimester gestational who performed VDRL in early pregnancy with negative results17.

The Ministry of Health, through Ordinance No. 2.815/98 and No. 572 of 2000 included labor analgesia in obstetric procedures table paid by SUS5. More than half of pregnant women 67 (63.8%) with vaginal deliveries did not receive analgesia in the ante partum period. This fact can be explained by the absence of the anesthesiologist at the moment of birth due to the scarcity of this professional. Other justifications would be the ignorance of teenagers about their right to receive analgesia or for fear of complications during childbirth as a result of this procedure.

However, it was observed that the percentage of teenagers who received analgesia 38 (36.2%) was higher than that found in the study, 23 (18.7%), in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, which has identified that this procedure is not carried out on a routine basis, however, epidural analgesia during labor and indicated by doctors who participated in the research as a means to promote the comfort of the delivering mother, contributing to a humanized delivery23.

As for the events and complications during childbirth, it was found that the majority of teenagers did not present, 116 (66.7 %) and 40 (90.9%), respectively. Among the complications that reached 4 (9.1%) of the teenagers, stand out retained placenta, 2 (4.5%) and pre-eclampsia and hypertension, both with 1 (2.3%). Such results resemble to those found in study that found in 89.9% women absence of health problems during childbirth24.

In relation to the presence of a companion during labor, 43 (97.7%) teenagers were not accompanied by family members, remaining only with medical and nursing staff in the delivery room or obstetric center. In this context, it should be noted that the quality of labor care depends on a cozy and favorable space conducive to the implementation of the recommended actions by the Program for Humanization of Prenatal and Birth (PNHP), among which are the presence of a companion and the involvement of the family during the delivery process.

The right to a companion was established by Decree 569/2000 and enforced by Law 11.108/2005. However, a recent study with respect to the conception of the professional categories of doctors and nurses about the presence of a companion during labor and childbirth, has identified that the doctors have recognized the importance of the companion, although consider this a controversial issue, because of the physical structure of the service is inadequate and the companion, generally, does not prepare to positively participate in this process23. On the other hand, nurses perceive the presence of the companion as a right of the mother, especially when it comes to teenagers, supported by specific legislation, and highlight the importance of good relationships and providing information to the companion on the conditions of the mother, in order to humanize the care..

Some scholars have pointed out the reasons alleged by health professionals against the presence of a companion, as the imposition of this rule by the institution, the absence of force of law, the fact of admission be made by SUS and the companion ends up disrupting the attention of the staff at the time of labor and delivery25.

With regard to the implementation of the delivery by the same professional who accompanied the prenatal period, it was observed that all pregnant teenagers underwent delivery with the duty doctor, not the doctor who accompanied her pregnancy. Such findings are discrepant from that established by the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (ECA) in Art. 8, § 2) Chapter I - The right to life and health, which determines that “the mother will be treated preferentially by the same doctor who accompanied them during the prenatal”4:11.

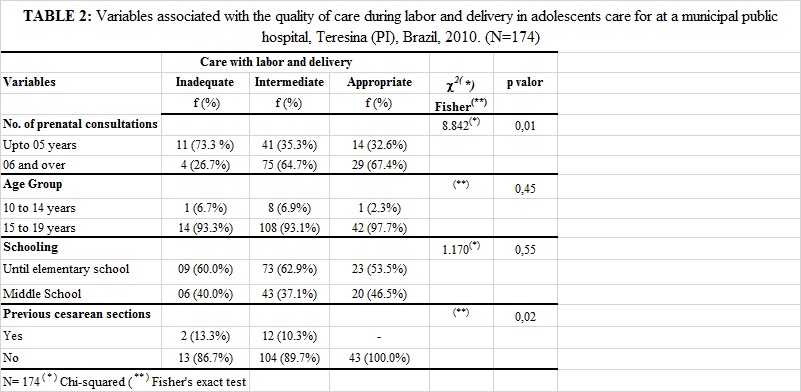

Regarding to the assessment of care for labor and delivery, it was found that 116 (66.7%) of the teenagers had birth care categorized as intermediate, 41 (23.6%) adequate, 15 (8, 6%) inadequate and 2 (1.1%) appropriate. Therefore, the percentage of adequacy of care was only 43 (24.7%); as this result was due to the fact that the items do not use the partograph and analgesia for the majority of teenagers.

For the nursing workers, working conditions, the harmony between the components of the work team and the impediment of interventionist practices are considered unnecessary elements that qualify care delivery26.

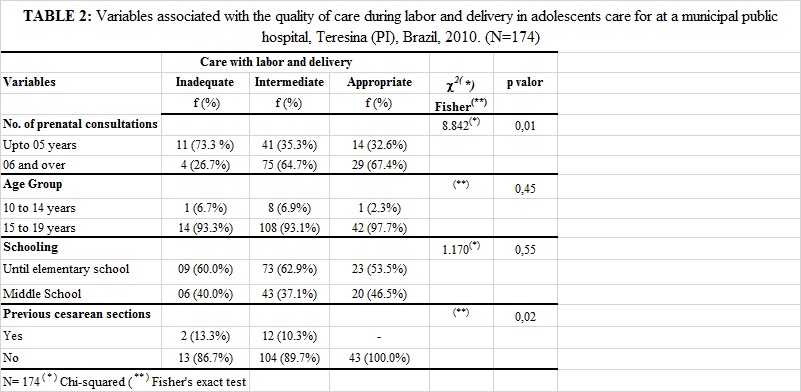

Regarding the association between the quality of care with labor and delivery and the variable numbers of prenatal consultations, age group, schooling and completion of previous cesarean sections, it can be noted that only the number of prenatal visits and the completion of previous cesarean sections are associated with the quality of labor care (p< 0.05). The teenagers who had six or more prenatal visits and did not have a history of cesarean sections obtained better quality care, as can be observed in Table 2.

These results indicate that the teenagers have been deserving of specialized care in health services, given that only 43 (24.7%) had adequate care. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the quality of care under the technical point of view and the humanization of care, seen that humanizing childbirth does not mean performing or not interventional procedures, but rather to make the woman protagonist of this event, giving them freedom of choice in decision-making processes27 . Care should respect the dignity and autonomy of women, ensuring the creation of strong family ties and a beginning of life with good physical and emotional condition towards the baby.

CONCLUSION

The study pointed to the need for improving the quality and humanization of care during labor and the childbirth process. To do so, we must break with the paradigm in which the health quality is linked to the accumulation of technologies and highly specialized personnel. Guide to deploy a new service design, whose actions are focused on individuality of the teenager.

Organizing the care network requires adequacy of health services to individual and specific needs of teenagers, with respect for the principles of ethics, privacy, confidentiality and secrecy, aiming to implement a comprehensive and resolutive care.

Considering the importance of this theme, it is recommended that the prenatal are clarified the reproductive rights of women in labor and delivery, with emphasis on the warranty of the companion in the pre-delivery, delivery and post-delivery, in addition to the analgesia in normal delivery. It is recommended to combine scientific knowledge to humanization, which is the challenge of health care services in the qualified care of childbirth.

It is suggested that the multidisciplinary team receive continuing education to keep up with the evolution of labor of teenagers, including the use of the flow chart to identify dystocias and the real need of the realization of cesarean sections, thus improving the quality of care.

This research presents a limitation related to the insufficiency of records in of some the variables studied, which complicates the identification of deficiencies in the care process to the teenager during labor and childbirth. These data are essential for the achievement of results that will contribute to the improvement of the quality of care. It is recommended, therefore, that the nursing records are made with quality, since they incorporate evaluation of care practices.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Pregnant teenagers: delivering on global promises of hope. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. [citado em 15 jan 2013]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241593784/en/

2. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Portal da Saúde. Notícias. Brasil acelera redução de gravidez na adolescência. 2010. [citado em 10 de janeiro de 2013]. Disponível em: http://portal.saude.gov.br

3. Davis-Floyd R. The technocratic, humanistic and holistic paradigms of childbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2001;48: 5-23.

4. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2006.

5. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Políticas de Saúde. Área Técnica de Saúde da Mulher. Parto, aborto e puerpério: assistência humanizada à mulher. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2001.

6. Nagahama EEI, Santiago SM. A institucionalização médica do parto no Brasil. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2005; 10: 651-7.

7. Osava RH, Mamede MV. A assistência ao parto ontem e hoje: a representação social do parto. J Bras Ginecol. 1995; 105: 3-9.

8. Rede Nacional Feminista de Saúde, Direitos Sexuais e Direitos Reprodutivos. Humanização do Parto: dossiê. São Paulo: Rede Feminina de Saúde; 2002. [citado em 23 de jan de 2013]. Disponível em: http://www.redesaude.org.br/hotsite/2002/index.html

9. Diniz CSG. Humanização da assistência ao parto no Brasil: os muitos sentidos de um movimento. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2005; 10: 627-37.

10. McCallum C, Reis AP. Re-significando a dor e superando a solidão: experiências do parto entre adolescentes de classes populares atendidas em uma maternidade pública de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2006; 22:1483-91.

11. Boaretto MC. Avaliação da política de humanização ao parto e nascimento no município do Rio de Janeiro [dissertação de mestrado]. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública; 2003.

12. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Maternidade segura. Assistência ao parto normal: um guia prático. Genebra (Swi): OMS; 1996.

13. Ministério da Saúde (Br).Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Saúde do adolescente: competências e habilidades. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2008.

14. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Contagem da População. 2010. [citado em 10 jan 2013]. Disponível em: http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br.

15. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Portaria nº 569/GM em 1 de junho de 2000. [citado em 13 jan 2013]. Disponível em: http://drt2001.saude.gov.br/sas/portarias/port2000/gm/gm-569.htm.

16. Vuori H. Garantia de calidad em Europa. Salud Publica (Mexico). 1993; 35: 291-7.

17. Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância (UNICEF). Ministério da Saúde (Br). Departamento de Vigilância, Prevenção e Controle de DST e AIDS. Como prevenir a transmissão vertical do HIV e da Sífilis no seu município: guia para profissionais de saúde. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2008.

18. World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985; 2:436-7.

19. Nader PRA, Cosme LA. Parto prematuro de adolescentes: influência de fatores sociodemográficos e reprodutivos, Espírito Santo, 2007. Esc Anna Nery. 2010; 14: 338-45.

20. Metello J, Torgal M, Viana R, Martins L, Maia M, Casal E, et al. Desfecho da gravidez nas jovens adolescentes. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2008; 30: 620-5.

21. Santos GHN, Martins MG, Sousa MS, Batalha SJC. Impacto da idade materna sobre os resultados perinatais e via de parto. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2009; 31: 326-34.

22. Borba AS, Brandim MR, Nogueira NN. Análise situacional da assistência obstétrica e perinatal em Maternidades de Teresina. Teresina (PI): UNICEF; 2001.

23. Busanello J. As práticas humanizadas no atendimento ao parto de adolescentes: análise do trabalho desenvolvido em um Hospital Universitário do extremo sul do Brasil [dissertação de mestrado]. Rio Grande (RS): Universidade Federal do Rio Grande; 2010.

24. Almeida SDM, Barros MBA . Eqüidade e atenção à saúde da gestante em Campinas (SP), Brasil. Rev Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2005; 17:15-25.

25. Nagahama EEI, Santiago SM. Práticas de atenção ao parto e os desafios para humanização do cuidado em dois hospitais vinculados ao Sistema Único de Saúde em município da Região Sul do Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008; 24:1859-68.

26. Busanello J, Keber NPC, Lunardi Filho WD, Lunardi VL, Sassi RAM, Azambuja EP. Parto humanizado: concepção dos trabalhadores de saúde. Rev enferm UERJ. 2011; 19: 218-23.

27. Seibert SL. Medicalização x humanização: o cuidado ao parto na história. Rev enferm UERJ. 2005; 13: 245-51.