OR (Odds Ratio) for a confidence interval (CI) of 95% for the odds ratio of prevalence; (*) p (Adjusted by gender); (**) (p <0.05)

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Octogenarians in rural and urban settings: socioeconomic comparison, morbidities and quality of life

Darlene Mara dos Santos TavaresI; Amanda Gonçalves RibeiroII; Pollyana Cristina dos Santos FerreiraIII; Nayara Paula Fernandes MartinsIV; Maycon Sousa PegorariV

I

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Associate Professor, Department of Nursing Education and Community Health of the Undergraduate Nursing Course. Federal University of

Triangulo Mineiro. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: darlenetavares@enfermagem.uftm.edu.br

II

Student of the Federal University of of Triangulo Mineiro, Undergraduate Nursing Course. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail:

mandy.ribeiro93@hotmail.com

III

Nurse. Master in Health Care. Substitute Professor at the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Professor, Department of Social Medicine. Researcher of

Research Group on Public Health. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: pollycris21@bol.com.br

IV

Nurse. Master in Health Care, Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Substitute Professor at the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Professor at

the Department of Social Medicine. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: nayara.pfmartins@gmail.com

V

Physiotherapist. Master in Health Care, Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Researcher at the Research Group on Public Health. Uberaba, Minas Gerais,

Brazil. E-mail: mayconpegorari@yahoo.com.br

VI

Funding sources:

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa

de Uberaba.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2015.5961

ABSTRACT

This cross-sectional, observational, analytical study compared socioeconomic variables, self-reported morbidity and quality of life of octogenarians resident in Uberaba, 326 in the urban and 74 in the rural area. Data was collected in 2008 and 2010, using BOMFAQ, WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD. Descriptive analysis, chi-square and Student t-tests, and multiple linear and logistic regressions (p<0.05) were applied. Octogenarians were predominantly women in urban areas and men in rural areas. Marital status and education were associated with place of residence. Octogenarians in the urban area had poorer health and scored lower in the physical and social relations domains and in the autonomy and past, present and future activities facets, while rural octogenarians scored lower in the environment domain and sensorial functioning facet. These results may support specific health measures for this population, considering the peculiarities of the environment they live in. Keywords: Elderly, 80 and over; urban population; rural population; health of the elderly.

INTRODUCTION

Population aging has been occurring at an accelerated speed. It is estimated that in the next two decades, the number of elderly will exceed 30 million people, corresponding to 13% of world population1. In Brazil, considering the period of 1999-2009, there was a percentage increase in this age group, from 9.1% to 11.3% in the total population, corresponding in 2009 to 21 million people aged 60 years or older2.

The increase in life expectancy is also a worldwide phenomenon. Individuals aged 80 years or older are the fastest growing age group in world3, and they may reach to 15% of the population in 20202. In Brazil, among the elderly, 14.4% are octogenarians, representing 1.5% of the population. In Uberaba, Minas Gerais, place of interest of this research, the percentage of octogenarians corresponds to 1.6%, which is above the national average4.

Such a scenario has led to discussions between health researchers and promoters of social policies on the challenges that increased longevity has imposed to most societies, both developed as the developing ones5.

In this perspective, the environment where the elderly live has been an object of research. But we can also see the need for research that widen knowledge on the subject of aging in rural areas compared to urban areas, in order to meet more equally the concerns of a greater number of Brazilian elderly 6.

Thus, this study aimed to compare the socioeconomic variables, the self-reported morbidity and quality of life (QOL) of elderly patients living in urban and rural areas of a municipality of Minas Gerais.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The aging population brings with it the need for a look to health in this age group. The social and demographic indicators have shown that the elderly group has been growing significantly, thus new requirements have become necessary in the context of public health policies for the care of these clients 2.

The scientific literature have shown that the population living in rural areas age like those living in the urban area; however, literature points to a reality in which poverty, geographical isolation, low educational levels, poorer households, transport limitations, chronic health problems and separation from the social and health resources prevail5.

Study performed with octogenarians of the rural area of Encruzilhada do Sul-RS observed a percentage of 10.6% of those aged 80 years or older. Of these, the majority were female, widowed and retired. Among the self-reported morbidity, systemic arterial hypertension, back problems, rheumatism, insomnia and cataract were highlighted5.

Regarding the presence of comorbidities, it is known that as age increases, the greater the chances of the elderly acquire a chronic disease2, which may have an adverse impact on their QOL. Data from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBGE) show that only 22.6% of people aged 60 years or older report not presenting any disease, and this percentage reduces to 19.7% among those aged 75 years or older2.

Quality of life has also been object of studies in Brazil. In comparing it among the elderly residing in urban and rural areas, research conducted in Paraiba found that living conditions in these environments, although different, do not influence the QOL of these elderly. However, lack of financial resources was associated with lower QOL scores among those with lower income6.

Although some studies address older seniors, there is still lack of knowledge production about the health conditions of the oldest old7.

It is noteworthy that understanding the health conditions of the oldest old favors targeted interventions in order to meet their demands and provide improvements that may impact on their QOL7.

Thus, it is important to study the octogenarians' health conditions in urban and rural areas, since the process of life and aging can give them unique characteristics, from different contexts and realities.

METHODOLOGY

This research is part of two larger projects conducted by the Research Group on Public Health, Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro (UFTM), with older people in urban and rural areas in the city of Uberaba, Minas Gerais in 2008 and 2011, respectively. These studies are analytical, cross-sectional and observational type, with household survey.

In the urban area the sample was calculated based on 2,892 elderly, considering 95% confidence, 80% test power, margin of error of 4% for interval estimates and an estimated ratio of π = 0.5 for the proportions of interest. Participants were 2,142 elderly in 2008.

To compose the population of the rural area, we obtained in June 2010, with the family health teams (ESF), the number of elderly registered according to each coverage area. The rural area of the municipality has 100% of coverage by the ESF, totaling 1,297 registered elderly. At the end of data collection, we had interviewed 850 elderly.

We included in this study elderly people living in rural and urban areas of Uberaba-MG, aged 80 and older who did not have cognitive decline. Thus, 326 seniors in urban areas and 74 in rural areas participated.

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was applied before starting data collection in order to perform the cognitive assessment of the elderly. In the urban area, we used the short version validated by researchers of the Projeto Saúde, Bem Estar e Envelhecimento (Health, Welfare and Aging Plan - SABE)8, and, in the rural area, we used the translated and validated instrument in Brazil9. Both instruments enable tracking the presence of cognitive decline, and the education of the elderly is considered to establish the cut-off point. The change of instrument between the two locations is justified due to the fact the collection have occurred at different times, and the researchers perceived that the translated and validated instrument in Brazil9 would be more appropriate to perform the cognitive assessment of the population living in the rural area.

We used part of the Brazilian Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (BOMFAQ), which was adapted to the Brazilian reality10, in order to obtain socioeconomic variables and self-reported morbidities.

To assess the QOL, we used the Brazilian validated versions of the World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)11 and of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment for Older Adults (WHOQOL-OLD)12.

The variables analyzed were: sex, age, marital status, education, household settings, individual monthly income, self-reported morbidities, domains of QOL assessed by the WHOQOL-BREF (physical, psychological, social relationships and environment) and facets of WHOQOL-OLD (sensory abilities; autonomy; past, present and future activities; social participation, death and dying and intimacy).

The interviews were subjected to review and coding. Two electronic databases were built in Excel®, one for the urban area and one for the rural area.

The collected data were processed in a personal computer for two people, in duplicate, to verify the consistency of the data. When there were inconsistencies between the bases, we proceeded to correction by consulting the original interview. For this study study we selected on the databases of the urban and rural areas the seniors who met the inclusion criteria, thus making up a single database.

Data were transported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17.0, for assessment. Statistical analysis was performed using simple frequency distribution, mean and standard deviation. To compare categorical variables we used the chi-square test and to the numeric variables we used the Student's t-test (p <0.05). Each WHOQOL-BREF domain and WHOQOL-OLD facets were analyzed separately.

In order to minimize possible confounding factors, the variables that were significantly associated (p <0.05) with the place of residence, were adjusted according to gender (male and female) from the multiple logistic regression model for the socioeconomic variables and morbidity, and from the multiple linear regression for the variables related to QOL. For this analysis all variables were transformed into dichotomous and the associations were considered significant when p <0.05.

The projects were submitted to the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings of UFTM and approved under the protocols No. 897 and No. 1477, respectively. The objectives of the research were presented and the doubts were clarified. After the elderly signed the Informed Consent Form, we started the interview.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We verified higher percentage of women in urban areas (62.9%), and of men in rural areas (58.1%); and the average age for octogenarians in the urban area was 84.4 years old (SD = 3.83) and in the rural area, 83.8 years old (SD = 3.02).

Study conducted with octogenarians and nonagenarians, from urban and rural areas of Sideropolis-SC, found consistent data, in which the average age was 85.06 years old13. It is noteworthy that in rural areas the average age was slightly lower than the urban area. In rural areas there may be poor access to health services due to difficulties with transportation and geographical isolation. These difficulties can be experienced more intensely among octogenarians of these locations, due to the greater fragility that derives from the aging process and from approaching the end of life. In this case, the family acts as the main source of support for the elderly5. The health team working in the rural areas must be attentive to the specific characteristics of this age and also stimulate the link between the elderly and family14.

The predominance of men living in rural areas contradicts national studies performed with octogenarians living in these areas, since in those studies there was a higher percentage of women5,15. During data collection, although it has not been the focus of this study, it was observed that women migrate more often with their children to urban areas when children seek study and employment opportunities. In contrast, older men remain working in the country in order to provide for the family, even at older ages. This fact may explain, in part, the higher percentage of men in rural areas and women in urban areas. Additionally, the predominance of women in urban areas may reflect the higher life expectancy among women and the fact that they have a more fragile health status than men, requiring the displacement for the urban area to be closer to health services and senior care14.

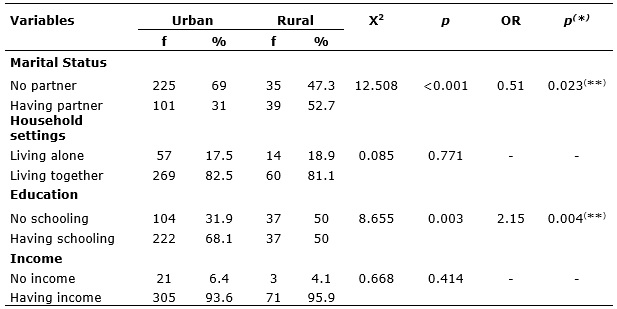

The comparison of socioeconomic variables of octogenarians, according to place of residence, after the analysis adjusted by gender, is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1:

Proportion of elderly according to place of residence and analysis adjusted by gender for socioeconomic variables. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, 2008 and 2011.

OR (Odds Ratio) for a confidence interval (CI) of 95% for the odds ratio of prevalence; (*) p (Adjusted by gender); (**) (p <0.05)

For socioeconomic variables, after adjustment by gender, marital status (OR = 0.51; 95% CI: 0.29-0.91, p = 0.023) and education (OR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.28-3.63; p = 0.004) remained associated with place of residence, according to Table 1.

We observed a higher proportion of elderly people living in urban areas who had no partner in relation to elderly people living in the rural area. It is noteworthy that in both groups the highest percentage of elderly lived together, both in the urban (82.5%) and in rural areas (81.1%), Table 1. Similar results were observed in research carried out with octogenarians residents in Rio Grande do Sul, where there was a higher proportion of unmarried elderly in urban areas compared to rural areas (p = 0.046)15. This situation may be related to the fact that there is a higher percentage of women in urban areas and men in rural areas. A study performed with octogenarians in Encruzilhada do Sul-RS verified predominance of widows and married men, following the national trend5.

It is important that health professionals recognize the marital status of octogenarians in order to identify support networks within the family. Moreover, it is relevant to check whether the elderly who have no companion live alone and/or with other seniors, since that in this age group octogenarians may require closer monitoring because of their health status.

Regarding the educational level, the proportion of elderly in the rural area who had no schooling was higher compared to the urban area. Research conducted with octogenarians of Porto Alegre-RS also found a higher proportion of elderly people with no schooling in rural areas compared to the urban area ( p=0.022)15. It is possible that this difference is related to the difficulties of access to school, which is experienced in the rural areas15, as well as cultural factors, since education was not valued in the past16.

Most octogenarians referred having individual monthly income, corresponding to 93.6% in urban areas and 95.9% in rural areas. There was no significant difference between the groups, Table 1. In contrast, a study in Rio Grande do South showed higher proportion of elderly people without income in rural areas compared to urban areas (p=0.017)14. Income is an important factor to be identified, since it may limit access to health and social services, generating an impact on the QOL of elderly 16.

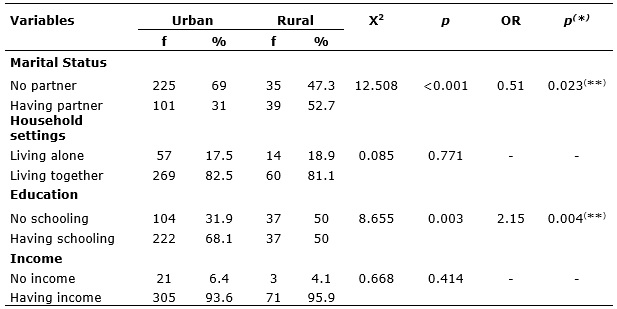

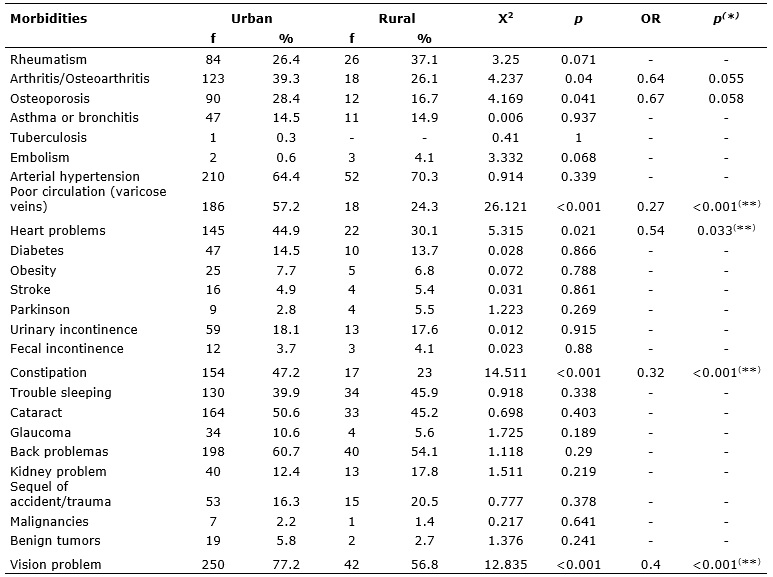

Morbidities reported by octogenarians, according to place of residence and the analysis adjusted by gender, are listed in Table 2. The results with statistically significant association will be presented after adjustment for the control variable.

Table 2:

Proportion of morbidity referred by octogenariansaccording to place of residence and analysis adjusted by gender. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, 2008 and 2011.

OR (Odds Ratio) for a confidence interval (CI) of 95% for the odds ratio of prevalence; (*) p (Adjusted by gender); (**) (p <0.05)

In comparing the groups, the proportion of elderly in urban areas who reported having poor circulation (OR = 0.27; 95% CI: 0.15-0.48; p <0.001), heart problems (OR = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.31-0.95; p = 0.033), constipation (OR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.18-0.59; p <0.001) and vision problems (OR = 0, 40; 95% CI: 0.23-0.68; p <0.001) was significantly higher to the elderly in the rural area, according to Table 2.

Study conducted in Sao Paulo, Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain, found that circulatory changes were among the most reported morbidities by octogenarians 17. In this research, the highest proportion of octogenarians living in the urban area who reported circulation problems may be related to the predominance of women in this locality, since the scientific literature has shown higher prevalence of this condition in women and in older ages 18,19.

The highest proportion of octogenarians living in the urban area who reported constipation may also be related to the higher percentage of women. Population-based study developed in Pelotas-RS showed higher prevalence of constipation among women20. Another factor that may interfere is the low intake of laxatives foods such as some fruit and vegetables 21. Thus it is possible that the availability of these foods in the rural area may have contributed to the lower proportion of elderly people with constipation in this area.

It is assumed that the higher proportion of octogenarians with heart problems in urban areas is due to greater exposure to risk factors in this location. A survey conducted in Anchieta-ES, which evaluated risk factors for cardiovascular problems, found higher prevalence of people living in urban areas who were physically inactive, consumed soft drinks five or more days a week and were overweight or obese, compared to people living in the rural area22. Cardiovascular problems can negatively interfere in people's lives. Thus, health professionals should be able to offer service, covering not only the biological aspects, but also the psychological needs, favoring the development of the disease coping mechanisms23.

The proportion of octogenarians with vision problems in urban areas was higher than in the rural area. Vision problems often affect the elderly, and about 90% need to use lenses to help them see properly24. It is possible that in the rural areas, where there is a gap of health services, the assessment of the vision of the elderly is more restricted, and there may be underdiagnosis.

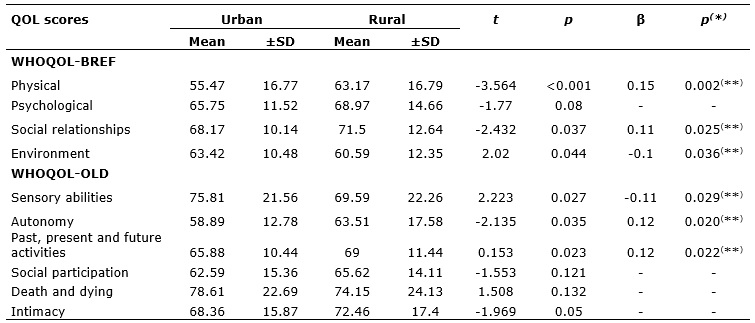

Table 3 shows the QOL scores for the domains of the WHOQOL-BREF and the facets of WHOQOL-OLD, according to place of residence and analysis adjusted by gender.

Regarding QOL measured by WHOQOL-BREF, after adjustment by gender, it was found that octogenarians living in the city had significantly lower mean scores in the physical domain (β = 0.15; p = 0.002) and social relationships (β = 0.11; p = 0.025) when compared to those living in the rural area, as shown in Table 3. In contrast, octogenarians living in the rural area had significantly lower mean scores in the environmental domain (β = -0.10; p = 0.036) than those living in urban areas, Table 3.

Table 3:

Comparison of QOL scores of the WHOQOL-BREF and WHOQOL-OLD, according to place of residence and analyses adjusted by sex. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, 2008 and

2011.

(*) p (Adjusted by gender, using multiple linear regression); (**) (p <0.05).

The significantly lower scores in the physical domain among octogenarians of the urban area may be related to the greater predisposition to fragility in this age group, making it difficult to stay in the rural area14. Thus, it is assumed that the elderly who have worse physical condition seek reside in urban centers, to be closer to health services and family support.

Octogenarians living in the urban area also had significantly lower scores in the domain social relationships when compared to those of the rural area. In the urban area, usually, there is a smaller establishment of affective bonds between neighbors and others, which can lead to greater social isolation among those in older age6.

As for the lower scores in the environmental domain among octogenarians of the rural area, we observed during data collection that there is a concern of the elderly in relation to security, which reflects the lack of policing in this location, leaving them more susceptible to violence. This may have influenced the results obtained. Moreover, in the rural are there are fewer opportunities for leisure and recreation activities, difficulties with transportation and access to entertainment in cities25,26, which may have contributed to the impact on QOL, evaluated by this domain.

In WHOQOL-OLD, even after adjusting for gender, octogenarians of the rural area had significantly lower mean scores than in the urban area on the facet sensory abilities (β = -0.11, p = 0.029). However, those living in urban areas had lower average scores to those of the rural area in the facets autonomy (β = 0.12; p = 0.020) and past, present and future activities (β = 0.12; p = 0.022), Table 3.

The elderly in the rural area had lower scores on the facet sensory abilities in relation those of urban area. The limitations arising from the decrease in sensory abilities can interfere with social interactions of the elderly. Thus, it is salutary that health professionals identify these losses, that natural in the aging process, seeking to differentiate them from pathological changes and to provide early intervention27. In the rural area, the loss of the senses is worrying, especially because it can bring greater health problems due to the physical characteristics of the environment, which is often inadequate to the octogenarians' needs.

The higher score on the facet autonomy among octogenarians of the rural area may represent that the ability to make decisions is preserved, and that the feeling that they feel useful, listened to and respected by society still remains28. However, poorer health conditions among the elderly in the urban area may have consequences such as greater dependence on others, also interfering with the autonomy and reflecting the lower scores in this facet.

Urban octogenarians had lower mean score compared to rural elderly in the facet past, present and future activities. This facet assesses satisfaction of the elderly and recognition for the achievements earned in life and future prospects12. It is possible that the health status of urban elderly, together with alterations inherent to the aging process, is not favoring future aspirations. Therefore, it is important that the health team and relatives encourage the elderly to seek new achievements in life.

CONCLUSION

In the present study it was found predominance of octogenarian women residing in urban areas and men in rural areas. After adjusting for the control variable, marital status and education level remained associated with place of residence, and there was a higher proportion of elderly people in urban areas who had no partner in relation to those of the urban area. In contrast, there was higher proportion of elderly people with no schooling in the rural area.

As regards morbidities, octogenarians of the urban area showed poorer health, referring with a greater proportion to poor circulation, heart problems, constipation and vision problem than those of the rural area.

On the QOL, urban octogenarians scored lower in the physical domain and in social relationships and in the facets autonomy and past, present and future activities. On the other hand, octogenarians living in the rural area obtained lower scores than those living the urban area in the environmental domain and in the facet sensory abilities.

These results point to the need for a new look on the health services to octogenarians, considering the environment in which they live. It was found that some aspects were most impacted in urban areas, such as health status and QOL. However, octogenarians living in rural areas also face some predicaments related to socioeconomic factors and the domains and facets of QOL.

Health professionals should be prepared to attend this part of the oldest old, in order to promote not only longevity but also QOL. In this sense, the monitoring of the ESF becomes essential to identify factors related to the environment where they live, that may interfere with health status and QOL in elderly, in order to intervene early.

Although this study has limitations, such as the non-diagnostic-confirmation of self-reported morbidities and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow establishing the relationships of cause and effect between variables, it enabled increasing knowledge of the peculiar characteristics of this clientele, considering the interference factors related to place of residence.

REFERENCES

1.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Projeção da população do Brasil por sexo e idade para o período de 1980-2050. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, 2007. [citado em 28 out 2012] Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/projecao_da_populacao/default.shtm

2.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Síntese dos indicadores sociais: uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão, 2010. [citado em 28 out 2012] Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/indicadoresminimos/sinteseindicsociais2010/SIS_2010.pdf

3.Kirkwood TBL. A systematic look at an old problem: as life expectancy increases, a systems-biology approach is needed to ensure that we have a healthy old age. Nature. 2008; 451:644-7.

4.Ministério da Saúde (Br). DATASUS. Informações de Saúde. 2010. [citado em 02 nov 2012] Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/popmg.def.

5.Morais EP, Rodrigues RAP, Gerhardt TE. Os idosos mais velhos no meio rural: realidade de vida e saúde de uma população do interior gaúcho. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2008; 17:374-83.

6.Martins CR, Albuquerque FJB, Gouveia CNNA, Rodrigues CFF, Neves MTS. Avaliação da qualidade de vida subjetiva dos idosos: uma comparação entre os residentes em cidades rurais e urbanas. Estud interdiscip envelhec. 2007; 11:135-54.

7.Rosset I, Roriz-Cruz M, Santos JLF, Haas VJ, Fabrício-Wehbe SCC, Rodrigues RAP. Diferenciais socioeconômicos e de saúde entre duas comunidades de idosos longevos. Rev Saúde Pública. 2011; 45:391-400.

8.Icaza MC, Albala C. Projeto SABE: Minimental State Examination (MMSE) del estudio de dementia en Chile: análisis estatístico. OPAS; 1999.

9. Bertolucci PHF, Brucki SMD, Campacci SR, Juliano Y. O mini-exame do estado mental em uma população geral: impacto da escolaridade. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 1994; 52(1):1-7.

10.Ramos LR. Growing old in São Paulo, Brazil: assessment of health status and family support of the elderly of different socio-economic strata living in the community [these doctor]. London (UK): London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1987.

11.Fleck MPA, Louzada S, Xavier M, Chachamovich E, Vieira G, Santos L, et al. Aplicação da versão em português do instrumento abreviado de avaliação da qualidade de vida WHOQOL-bref. Rev Saude Publica. 2000; 34:178-83.

12.Fleck MPA, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version of the WHOQOL-OLD module. Rev Saude Publica. 2006; 40:785-91.

13.Schmidt JA, Dal-Pizzol F, Xavier FM, Heluany V. Aplicação do teste do relógio em octogenários e nonagenários participantes de estudo realizado em Siderópolis/SC. PSICO. 2009; 40:525-30.

14.Cabral SOL, Oliveira CCC, Vargas MM, Neves ACS. Condições de ambiente e saúde em idosos residentes nas zonas rural e urbana em um município da região nordeste. Geriatria & Gerontologia. 2010; 4(2):76-84.

15.Aires M, Paskulin LMG, Morais EP. Capacidade funcional de idosos mais velhos: estudo comparativo em três regiões do Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. Latino-Am Enferm. 2010; 18:1-7.

16.Inouye K, Pedrazzani ES. Nível de instrução, status socioeconômico e avaliação de algumas dimensões da qualidade de vida de octogenários. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2007; 15:742-7.

17.Santos AS, Karsch UM, Montañés CM. A rede de serviços de atenção à saúde do idoso na cidade de Barcelona (Espanha) e na cidade de São Paulo (Brasil). Ser Soc Soc. 2010; 102:365-86.

18.Ferrari DC, Monteiro ML, Malagutti W, Barnabe AS, Ferraz RRN. Prevalência de lesões cutâneas em pacientes atendidos pelo programa de internação domiciliar (PID) no município de Santos – SP. Conscientiae Saúde. 2010; 9(1):25-32.

19.Santos RFFN, Porfírio GJM, Pitta GBB. A diferença na qualidade de vida de pacientes com doença venosa crônica leve e grave. J Vasc Bras. 2009; 8(2):143-7.

20.Collete VL, Araújo CL, Madruga SW. Prevalência e fatores associados à constipação intestinal: um estudo de base populacional em Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil, 2007. Cad Saúde Pública. 2010; 26:1391-402.

21.Nesello LAN, Tonelli FO, Beltrame TB. Constipação intestinal em idosos frequentadores de um Centro de Convivência no município de Itajaí-SC. CERES. 2011; 6(3):151-62.

22.Yokota RTC, Iser BPM, Andrade RLM, Santos J, Meiners M, Marie MA, et al. Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças e agravos não transmissíveis em município de pequeno porte, Brasil, 2010. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010; 21(1):55-68.

23.Soares DA, Toledo JAS, Santos LF, Lima RMB, Galdeano LE. Qualidade de vida de portadores de insuficiência cardíaca. Acta Paul Enferm. 2008; 21:243-8.

24.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Cadernos de envelhecimento e saúde da pessoa idosa. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2007.

25.Braga MCP, Casella MA, Campos MLN, Paiva SP. Qualidade de vida medida pelo Whoqol-Bref: estudo com idosos residentes em Juiz de Fora/MG. Rev APS. 2011; 14(1):93-100.

26.Rodrigues LR, Melo e Silva AT, Ferreira PCS, Dias FA, Tavares DMS. Qualidade de vida de idosos com indicativo de depressão: implicações para a enfermagem. Rev enferm UERJ. 2012; 20(esp.2):777-83.

27.Tavares DMS, Gomes NC, Dias FA, Santos NMF. Fatores associados à qualidade de vida de idosos com osteoporose residentes na zona rural. Esc Anna Nery. 2012; 16:371-8.

28.Maués CR, Paschoal SMP, Jaluul O, França CC, Jacob Filho W. Avaliação da qualidade de vida: comparação entre idosos jovens e muito idosos. Rev Bras Clin Med. 2010; 8:405-10.