RESEARCH ARTICLES

Health and leisure among elderly rural diabetics with and without indications of depression

Darlene Mara dos Santos TavaresI; Tamires Gomes dos SantosII; Flavia Aparecida DiasIII; Alisson Fernandes Bolina IV; Pollyana Cristina dos Santos FerreiraV

I

PhD in Nursing. Associate Professor, Department of Nursing Education and Community Health of the Nursing Graduation Course at the Federal University of

Triangulo Mineiro. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: darlenetavares@enfermagem.uftm.edu.br

II

Academic of the Nursing Graduation Course at the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Scientific Initiation Scholarship funded by the National Council

for Scientific and Technological Development. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: tamiresgomes_santos@hotmail.com

III

Master in Health Care. Substitute Professor of the Department of Nursing Education and Community Health of the Nursing Graduation Course at the Federal

University of Triangulo Mineiro. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: flaviadias_ura@yahoo.com.br

IV

Master Student in the Post-graduate Program in in Health Care, Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail:

alissonbolina@yahoo.com.br

V

Master in Health Care. Substitute Professor, Department of Social Medicine, Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro. Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail:

pollycris21@bol.com.br

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2015.4350

ABSTRACT

This study compared the health and recreation of elderly diabetics with and without indications of depression. We interviewed 104 elderly diabetics in rural areas of Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 2011 using as instruments the Geriatric Depression Scale Short and a semistructured based on Older Americans Resources and Services. Descriptive analysis and chisquare test (p<0.05) were performed. Most participants in both groups were female, aged 60-70 years, lived with a husband or partner, had 4-8 years' schooling, and income of one minimum wage. The elderly diabetics with indications of depression had proportionally worse self-perceived health, more diabetes-related complications, and greater use of drug combinations and insulin. This confirms the need for health measures to monitor elderly diabetics with indications of depression, with a view to establishing diagnosis and following up to minimize the impact of the disease on their daily lives. Keywords: Older adults; diabetes mellitus; rural population; depression.><0.05) were performed. Most participants in both groups were female, aged 60-70 years, lived with a husband or partner, had 4-8 years' schooling, and income of one minimum wage. The elderly diabetics with indications of depression had proportionally worse self-perceived health, more diabetes-related complications, and greater use of drug combinations and insulin. This confirms the need for health measures to monitor elderly diabetics with indications of depression, with a view to establishing diagnosis and following up to minimize the impact of the disease on their daily lives.

Keywords: Older adults; diabetes mellitus; rural population; depression.

INTRODUCTION

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), in 1999, the elderly accounted for approximately 9.1% of the Brazilian population and in 2009, for 11.3%1.

This increase in the proportion of elderly in Brazil is correlated with the epidemiological transition, characterized by changing of the profile of morbidity and mortality, which showed a progressive decrease in deaths from infectious diseases and increased chronic morbidities2. Among these, the Diabetes Mellitus (DM) stands out.

According to the National Survey by Sample of Households, in 2008, 16.1% of Brazilian elderly people had DM1. It is noteworthy that Brazil is primarily an agrarian country and many of its municipalities are classified as rural. Nevertheless, researches on aging have been occurring mainly in urban areas, which generates a gap on the real needs of the rural population3. So, this study will make a cut for the rural elderly population with DM in order to contribute to the health care policy for these elderly.

Thus, the objectives of this study were to describe the sociodemographic and economic characteristics of diabetic elderly people with and without indicative of depression and to compare the health and pleasure among diabetic elderly people living in rural areas, with and without indicative of depression.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Survey in Sweden observed prevalence of diabetes among the elderly in rural areas (16.1%) in relation to those who lived in urban areas (6.3%)4. In Brazil, research conducted in Minas Gerais noted that elderly people living in rural areas were less likely to have the disease 5.

DM is part of a group of metabolic diseases characterized by excess glucose resulting from a disorder in insulin secretion and/or action6. Furthermore, it is evident that this morbidity may favor feelings of impotence as well as the occurrence of depressive symptoms 7.

A possible explanation for the development of depression in people with diabetes is related to the activity of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, causing metabolic disorder. Thus, hyperglycemia occurs due to stimulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis, protein degradation, increased numbers of glucocorticoids in adipose tissues and inhibition of glucose receptors in adipose and muscle tissues. Moreover, there is blockage of serotonin 5-HT receptors, which predisposes to the development of depression8.

Despite this, there is no consensus in the scientific literature regarding DM and depression. Study with older people in rural India found an association between depression and DM9. However, other research obtained that older adults with DM are not more affected by depression than those who have other chronic conditions10.

In addition, studies conducted in Brazil found that depressive symptoms are associated with illiteracy, female gender, advanced age, presence of comorbidities, low education, drug use, little physical activity and lower self-care in older people with diabetes11,12.

It should be noted that individuals with DM have their treatment aimed at changes in nutrition, medication use and physical activity. Thus, during treatment, they may experience feelings that hinder the acceptance of the disease and, accordingly, the adoption of healthy habits7. These factors, combined with the indicative of depression, can impact negatively on their health conditions.

METHODOLOGY

This study is part of Project Health and quality of life of the elderly population of rural Uberaba, developed by the Research Group in Public Health of the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro.

It is a home, cross-sectional observational research, developed in the rural municipality of Uberaba-MG. This city is 100% covered by four teams of the Family Health Strategy (FHS).

Study population consisted of 1,297 elderly people residing in the rural area of the municipality of Uberaba-MG. The FHS have provided a list containing the names and addresses of registered elderly, with the permission of the Municipal Health Secretariat.

Inclusion criteria were: being 60 years of age or older, residing in the rural municipality of Uberaba-MG, having no cognitive decline, claiming to have DM and agreeing to participate in the study.

Of the total of 1,297 people, 447 elderly were excluded due to change of address (117), cognitive decline (105), refusal to participate (75), not found after three attempts by the interviewer (57), death (11), hospitalization (3) and other reasons (57). So, 850 elderly were interviewed and 104 of these seniors met the inclusion criteria of this research. Considering the score obtained in the Geriatric Depression Scale (Short Version), two groups were constituted: older adults with DM and with indicative of depression (n = 32) and older adults with DM and with no indicative of depression (n = 72).

Interviews were conducted in the elderly people's homes by 14 trained interviewers. The community health workers helped to find the residences. Data were collected from June 2010 to March 2011.

The interviews were reviewed by field supervisors, who checked incomplete answers and inconsistency of responses. When necessary, the interview was returned to the interviewer to perform the adequate filling.

Cognitive decline was assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), translated and validated in Brazil. The cutoff point was: 13 for illiterates, 18 for 1 to 11 years of education and 26 for up to 11 years of education13.

To evaluate the indicative of depression, the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) was used; the short and adapted version in Brazil 14.

To characterize the sociodemographic, economic, health and leisure data, part of the questionnaire Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) was applied, adapted to the Brazilian reality 15.

There was investigation of the sociodemographic and economic (gender; age group; marital status; schooling; monthly individual income, in minimum wages; housing arrangement; reason of retirement); health (self-perceived health; health compared to 12 months ago; health compared to the health of others; monthly consultation; place of consultation; registration on Hiperdia; DM diagnostic time; complications; type of complications; medication; type of medication); leisure (performance of leisure; hobby; satisfaction in leisure activities) variables.

An electronic database was built in Excel® program and the data collected were processed in duplicate by two typists. The database was transported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 17.0, to perform the analysis.

Data were submitted to descriptive analysis using absolute and percentage frequencies. To compare the groups, the chi-square test for categorical variables (p <0.05) was applied.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research with Human Beings of the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro, Protocol No. 1477. After seniors signed the Informed Consent Form, the interview was conducted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

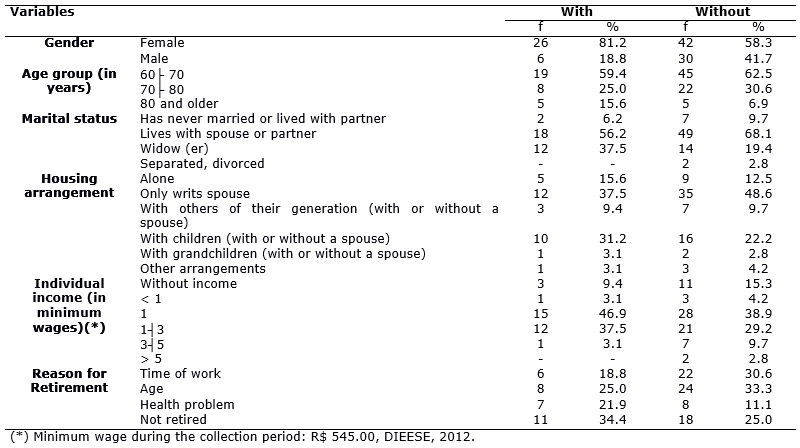

The sociodemographic and economic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1: Frequency distribution of sociodemographic and economic variables of the rural elderly with and without indicative of depression. Uberaba, Minas Gerais,

2012.

In both groups, the majority was women, with a higher percentage among elderly diabetics with indicative of depression compared to those without, as shown in Table 1. These data corroborate research conducted in southern Brazil, which found that 83.3% of diabetic elderly people with depression and 65.2% of those without depression were women16. This may be related to greater concern of women about their health and thus they are more frequent in health services, generating a greater chance of making the diagnosis of the disease and therefore undergoing treatment17.

There was prevalence of the age group of 60├70 years old, both for diabetic elderly people with and without indicative of depression, according to Table 1. It is noteworthy that 5 (15.6%) of diabetic elderly people with indicative of depression were 80 years old or older, according to Table 1. This result is consistent with research conducted in Southern Brazil, in which 58.7% of seniors with diabetes and depression and 60.2% of the elderly only with DM were between 60├70 years old16. It is evident that most of these individuals are young elderly, which indicates the need to create strategies that help in coping with this disease throughout life. The screening for depression in diabetic elderly people should be performed periodically. The Geriatric Depression Scale is a significant tool in the detection of depression in the elderly17.

However, the high percentage of elderly diabetics with indicative of depression in later life can be elucidated by excessive physical, mental and social losses occurring over the years, which favors the onset of depressive symptoms in these individuals11.

In both groups, the majority had a spouse/partner and lived only with their spouse. However, 12 (37.5%) diabetic elderly with indicative of depression were widowed, as shown in Table 1. This result is similar to a research conducted in rural areas of the United States, which verified the percentage of married seniors with DM in both groups of individuals with (39.1%) and without depressive symptoms (52.1%)18. This fact may be related to the migration of children to urban areas in search of job or study opportunities 19.

However, the high prevalence of widowhood among diabetic elderly with indicative of depression may be resulting from feelings experienced by these individuals during the mourning period due to the recent loss of relatives, especially the spouse, contributing to depressive symptoms11. In addition, some unfavorable situations of the aging process itself may also favor the appearance of this symptom, such as decreased health, decreased cognitive ability, decreased financial resources and social functions11.

Thus, FHS professionals should expand the social support network of elderly widowers. This can be done through incentives to maximize relationships with other people in the family circle and by encouraging participation in community activities that bring them pleasure and satisfaction.

There was prevalence of 4├8 years of education, with lower percentage among diabetic elderly with indicative of depression compared to those without. A study conducted in the urban area of Taiwan with diabetic elderly found that 30.1% had no schooling20. Another survey, developed in Southern Brazil, found that 64.4% of elderly patients with DM and without depression had less than four years of study16. These results are different from this research; however, these differences can be elucidated by the unique cultural aspects of each region or country.

The low level of schooling of older people may reflect on learning about self-care due to the difficulty in accessing information, as well as in the ability to seek the services they need. Added to this, these individuals may have some limitations in understanding the therapeutic procedures21 . In this sense, the health care professional, while providing care to seniors, must adapt the language to favor their understanding, aiming at effective communication.

There was prevalence of those receiving up to one minimum wage, with a higher percentage among diabetic elderly with indicative of depression compared to those without, as shown in Table 1. The prevalence of low income among diabetic elderly with and without indicative of depression in this study corroborates demographic data of census conducted in 2009, in which 43.2% of Brazilian elderly received up to one minimum wage1. The reduced income level of diabetic elderly can be a complicating factor in adherence to drug treatment and access to proper diet 22.

Among the elderly, the highest percentage has retired due to age in both groups. However, seven (21.9%) elderly with indicative of depression have retired due to health problems, according to Table 1. It is noteworthy that the National Institute of Social Security (INSS) found that most seniors (65.5%) living in rural areas have retired due to age23. This population may request retirement 5 years earlier than those in urban areas. It is stipulated 55 years old for women and 60 years old for men 23.

A significant portion of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression reported having retired due to health reasons, following those with no depressive tendency. It is evident that chronic diseases, often found in the elderly, can generate depressive symptoms in these individuals24, and may contribute to the deterioration of their health and thus intervene in the retirement reason.

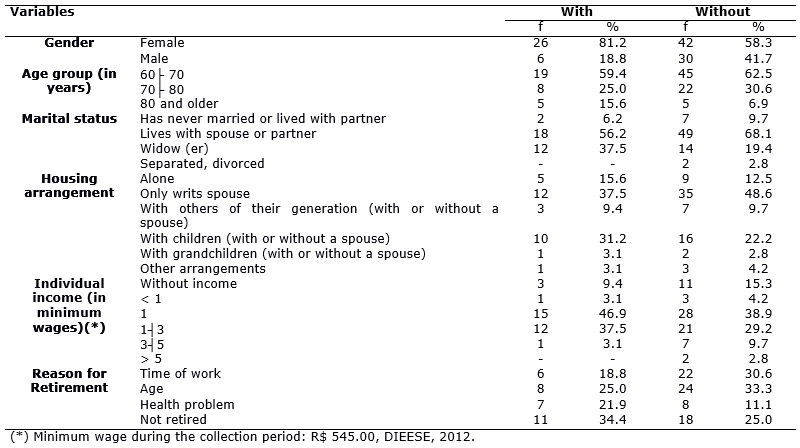

Health-related data of diabetic elderly are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2:

Distribution of health variables of diabetic elderly from rural areas with and without indicative of depression. Uberaba, 2012. (N=72)

There was a higher proportion of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression with negative self-perception of health compared to those without indicative of depression (X2=11.08; p=0.03), as shown in Table 2. The results showed inconsistency with research conducted in the urban area in a city in Minas Gerais, with diabetic elderly, which found that 50% of those with indicative of depression and 83.5% with no indicative mentioned their health status as good17. This inconsistency can be explained by the differences of area of residence of the elderly.

It is evident that the unfavorable perception of the health condition of diabetic patients is due to the limitations and complications of the disease 25 which, added to the indicative of depression, could justify the higher proportion of seniors who classified their health as poor.

Although the elderly diabetics with indicative of depression considered their health status worse than 12 months ago and those without indicative considered it equal, there was no significant difference between groups (X2=5.58; p=0.06), according to Table 2. This worse self-perception of health among diabetic elderly with indicative of depression may be resulting from the lack of intervention in the onset of symptoms, resulting in a worsening of the health condition throughout the days and thus in worsening health status. Thus, there is need for making the diagnosis of depression early, to be offered appropriate treatment.

When they compared their health with that of other people, the highest percentage was on the diabetic elderly patients in both groups who reported being better, with no significant difference between them (X2=1.49; p=0.47), according to Table 2. It is noteworthy that people with depression tend to have low self-esteem, which contributes to a worse self-perception of the health status17, compared to others of the same age.

Most diabetic elderly with and without indicative of depression did not perform monthly consultations for health control, with no statistical difference between groups (X2=0.01; p=0.97), as shown in Table 2. It is noteworthy that 25 (80.6%) of the elderly with indicative of depression and 47 (65.3%) of those without such a trend were registered in Hiperdia. However, private consultations predominated in both groups, with 10 (31.2%) in the first group and 22 (30.6%) in the second group (with no depressive tendencies). From these data, it is highlighted the importance of FHS professionals conduct home visits, enabling an active search for this elderly and thus their monitoring. However, the lack of transportation for professionals to conduct visits, the inadequate infrastructure of Basic Health Units, the shortage of materials needed to carry out the work, and the lack of understanding by the population in the functioning of the FHS policy26 may hinder the monitoring of these seniors.

Although there was no difference between groups (X2=3.18; p=0.36), most diabetic elderly with indicative of depression had longer diagnosis time of DM (11├│20 years) compared to those without indicative (0├│5 years), as shown in Table 2. Among the diabetic elderly, it is clear the difficulty in accepting the diagnosis, which demands, above all, restriction and modification of habits, imposed by the treatment. Thus, individuals with diabetes tend to alternate between moments of helplessness/hopelessness and moments of confidence in treatment7. Thus, it is necessary that professionals, through health education, discuss with diabetic seniors about the difficulties experienced in daily life and about ways of coping with the disease, minimizing the development of negative feelings about the chronicity of the disease and the appropriate treatment. The service must focus on prevention aimed at healthy aging and quality of life27. In this context, it is noteworthy that educational nursing interventions can help improving the health status and clinical parameters of individuals with chronic illnesses 28.

There was a higher proportion of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression with complications compared to those without this indicative (X2 =12.52; p=0.03), according to Table 2. The number and severity of complications of DM may be related to the increase of depressive symptoms 12. In this sense, there should be a periodic monitoring of diabetic elderly in order to identify the presence of complications.

The prevalent complications among diabetic elderly with indicative of depression were vision - 15 (55.6%) and heart problems - 7 (25.9%), whereas in those with no indicative were vision - 52 (81.2%) and kidney problems - 6 (9.4%). This diverges from study conducted in Southern Brazil, where it was observed that the prevalent comorbidities in diabetic elderly with depression were vascular (83.7%), muscle (81.3%) and kidney problems (54.4%); and in those without depression there was higher percentage of muscle (57.7%), vascular (42.2%) and kidney complications (26.8%)16.

The use of drugs for diabetes did not differ between the groups (X2=3.49; p=0.06), according to Table 2.

Opposite results were found in a study conducted in rural North Carolina, United States, which found that 51% of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression and 67.3% of those with no indicative did not use drugs18. There should be adoption of rational drug therapy in order to avoid unnecessary use, side effects and interactions of medicinal components. Thus, it is necessary that the health care team use means for the treatment and prevention with healthy practices8,11.

There was a higher proportion of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression using combined therapy and insulin compared to those with no indicative (X 2=8.07; p=0.04), as shown in Table 2. This diverges from a survey conducted in rural areas in the United States with diabetic elderly, which found that those with depression had lower percentage in the use of combined therapy (25.5%) than those who did not have depression (28.0%); however, there was no significant difference between these groups18.

Nevertheless, the highest proportion of indicative of depression among diabetic elderly in use of combined therapy in this study may be related to the increased number of medications that are often used in different times of the day and to the discomfort caused by the administration of insulin.

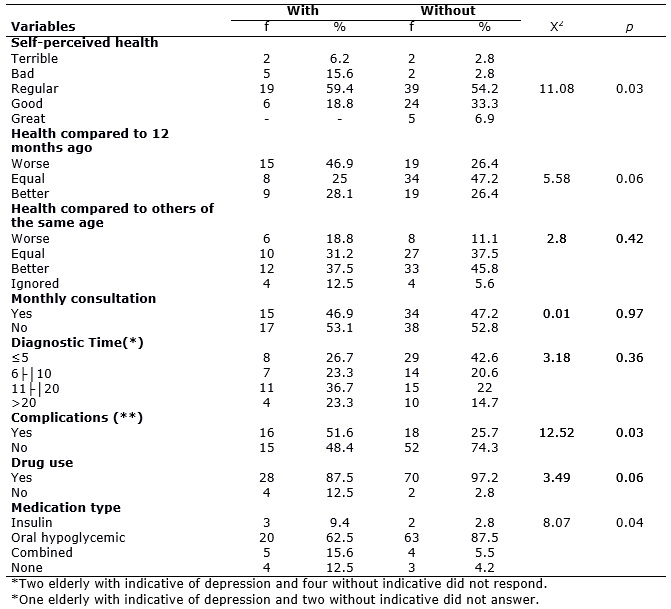

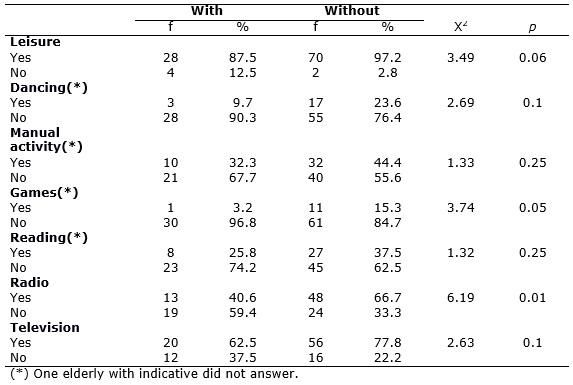

The distribution of leisure variables of the study population are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3:

Distribution of leisure variables of diabetic elderly living in the rural area, with and without indicative of depression. Uberaba, 2012. (N=72)

There was prevalence, in both groups, of the elderly who performed recreational activities, with no significant difference between them (X2 =3.49; p=0.06), as shown in Table 3. However, a lower percentage of diabetic elderly with indicative of depression claimed performing dance, manual activities, games, reading and watching television compared to those with no indicative, according to Table 3. These activities can provide social interaction, which contributes to the development of their own autonomy and control or reduction in depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress29. Furthermore, the elderly should engage in activities that make them feel useful, bring pleasure and happiness 19.

There was a higher proportion of diabetic elderly with no indicative of depression that listened to radio compared to those with no indicative (X 2=2.63; p=0.01), as shown in Table 3. This may be related to lack of interest or pleasure in activities that used to be usual, which is one of the common symptoms of depression30. In both groups, 23 (74.2%) with and 56 (77.8%) with no indicative of depression were satisfied with their leisure activities. Leisure is essential to keep the elderly inserted in society; thus, this aspect should be verified by the health team in their work process. They should identify what activities the elderly have an interest and seek joint strategies (client/professional) aiming at the implementation thereof.

CONCLUSION

Mostly diabetic elderly patients were female, aged between 60├70 years old, lived with their spouse or partner, had 4├8 years of schooling and income up to one minimum wage. There is highlight for the subjects with no indicative of depression who had retired due to age.

Diabetic elderly with indicative of depression had, proportionately, worse self-perceived health, more complications related to DM and increased use of combined drugs and insulin compared to those with no indicative of depression. Regarding leisure activities, a lower proportion of elderly people with depressive tendencies listened to the radio compared to those without such tendencies.

As for the limitations of this study, it can be mentioned the self-reported morbidities (without corroborating documents) and the cross-sectional design, that does not allow establishing cause and effect relationship between the variables investigated. Still, it was possible to deepen the knowledge about the sociodemographic characteristics as well as the health profile of older people with diabetes living in the rural areas, with and without indicative of depression.

However, results of this research denote the need for monitoring of elderly people with indicative of depression, aiming at establishing diagnosis. Based on that, an intervention directed to the peculiarities of each elderly may be planned. Actions aimed at identifying the impact of the disease on daily life and at pursuing strategies for expansion of leisure options, according to the preference of the elderly, should be prioritized.

REFERENCES

1.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2010. [citado em 27 jan 2015]. Disponível em: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/indicadoresminimos/sinteseindicsociais2010/SIS_2010.pdf.

2.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Atenção à saúde da pessoa idosa e envelhecimento. Série Pactos pela Saúde. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2010.

3.Martins CR, Albuquerque FJB, Gouveia CNNA, Rodrigues CFF, Neves MTS. Avaliação da qualidade de vida subjetiva dos idosos: uma comparação entre os residentes em cidades rurais e urbanas. Estud interdiscip envelhec. 2007; 11: 135-54.

4.Sjolund BM, Nordberg G, Wimo A, Strauss EV. Morbidity and physical functioning in old age: differences according to living area. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58: 1855-62.

5.Viegas-Pereira APF, Rodrigues RN, Machado CJ. Fatores associados à prevalência de diabetes auto-referido entre idosos de Minas Gerais. Rev Bras Estud Popul. 2008; 25: 365-76.

6.American Diabetes Association (ADA). Diagnosis and classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31: 55-60.

7.Peres DS, Santos MA, Zanetti ML, Ferronato AA. Dificuldades dos pacientes diabéticos para o controle da doença: sentimentos e comportamentos. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2007; 15: 1105-12.

8.Nascimento AB, Chaves EC, Grossi SAA, Lottenberg SA. A relação entre polifarmácia, complicações crônicas e depressão em portadores de diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Rev esc enferm USP. 2010; 44: 40-6.

9.Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Senthilkumar P, Gayathri K, Prince M, Jacob KS. Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009; 21: 372-8.

10.O'Connor PJ, Crain AL, Rush WA, Hanson AM, Fischer LR, Kluznik JC. Does diabetes double the risk of depression?. Ann Fam Med. 2009; 7: 328-35.

11.Fernandes MGM, Nascimento NFS, Costa KNFM. Prevalência e determinantes de sintomas depressivos em idosos atendidos na atenção primária de saúde. Rev RENE. 2010; 11: 19-27.

12.Moreira RO, Amâncio APRL, Brum HR, Vasconcelos DL, Nascimento GF. Sintomas depressivos e qualidade de vida em pacientes diabéticos tipo 2 com polineuropatia distal diabética. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 53: 1103-11.

13.Bertolucci PHF, Brucki SMD, Campacci SR, Juliano Y. O mini-exame do estado mental em uma população geral: impacto da escolaridade. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatria. 1994; 52: 1-7.

14.Frank MH, Rodrigues NL. Depressão, ansiedade, outros distúrbios afetivos e suicídio. In: Freitas EV, Py L. Tratado de geriatria e gerontologia. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2006. p. 376-87.

15.Ramos L R. Growing old in São Paulo, Brazil: assessment of health status and family support of the elderly of different socio-economic strata living in the community [tese de doutorado]. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London, 1987.

16.Blay SL, Fillenbaum GG, Marinho V, Andreoli SB, Gastal FL. Increased health burden associated with comorbid depression in older Brazilians with diabetes. J Affect Disord. 2011; 134: 77-84.

17.Faria ACNB, Barreto SM, Passos VMA. Sintomatologia depressiva em idosos de um plano de saúde. Rev Med Minas Gerais. 2008; 18: 175-82.

18.Bell RA, Andrews JS, Arcury TA, Snively BM, Golden SL, Quandt SA. Depressive symptoms and diabetes self-management among rural older adults. Am J Health Behav. 2010; 34: 36-44.

19.Tavares DMS, Gávea Junior SA, Dias FA, Santos NMF, Oliveira PB. Qualidade de vida e capacidade funcional de idosos residentes na zona rural. Rev RENE. 2011; 12: 895-903.

20.Bai YL, Chiou CP, Chang YY, Lam HC. Correlates of depression in type 2 diabetic elderly patients: a correlational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008; 45: 571-9.

21.Grillo MFF, Gorini MIPC. Caracterização de pessoas com Diabetes Mellitus tipo 2. Rev Bras Enferm. 2007; 60: 49-54.

22.Tavares DMS, Rodrigues FR, Silva CGC, Miranzi SSC. Caracterização de idosos diabéticos atendidos na atenção secundária. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2007; 12: 1341-52.

23. Ministério da Previdência Social (Br). Anuário Estatístico da Previdência Social. 2010. [citado em 27 jan 2015]. Disponível em: http://www.previdencia.gov.br/arquivos/office/3_111202-105619-646.pdf.

24.Borges DT, Dalmolin BM. Depressão em idosos de uma comunidade assistida pela estratégia de saúde da família em Passo Fundo, RS. Rev Bras Med Fam Comunidade. 2012; 7 (23): 75-82.

25.Francisco PMSB, Belon AP, Barros MBA, Carandina L, Alves MCGP, Goldbaum M, Cesar CLG. Diabetes auto-referido em idosos: prevalência, fatores associados e práticas de controle. Cad Saúde Pública. 2010; 26: 175-84.

26.Silva SA, Oliveira F, Spinola CM, Poleto VC. Atividades desenvolvidas por enfermeiros no PSF e dificuldades em romper o modelo flexneriano. Rev Enferm Centro O Min. 2011; 1: 30-9.

27.Oliveira MAS, Menezes TMO. A enfermeira no cuidado ao idoso na estratégia saúde da família: sentidos do vivido. Rev enferm UERJ. 2014; 22:513-8.

28.Luna NSA, Baeza MR, Castell EC, Santos FC, David HL, Castilho MMA. Intervención educativa: implementación de la agencia de autocuidado y adherencia terapêutica desde la perspectiva del paciente diabético. Rev enferm UERJ. 2013; 21: 289-94.

29.Navarro FM, Rabelo JF, Faria ST, Lopes MCL, Marcon SS. Percepção de idosos sobre a prática e a importância da atividade física em suas vidas. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2008; 29: 596-603.

30.Carreira L, Botelho MR, Matos PCB, Torres MM, Salci M. Prevalência de depressão em idosos institucionalizados. Rev enferm UERJ. 2011; 19: 268-73.