Note: Subscale 1 – Family: conversational partner and coping resource. // Subscale 2 – Family: resource in nursing care. // Subscale 3 – Family: burden *Possible punctuation range

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Impact on nurses' attitudes of an educational intervention about Family Systems Nursing

Andréia Cascaes CruzI; Margareth AngeloII

I

Nurse. PhD in Sciences. Leader of the Study Group in Nursing and Family

(GEENF – "Grupo de Estudos em Enfermagem e Família", in Portuguese

language). University of São Paulo, Nursing School, São Paulo, Brazil.

E-mail: deiacascaes@gmail.com

II

Nurse. PhD in Sciences. Full Professor of the Maternal-Infant and

Psychiatric Nursing Department. Leader of the Study Group in Nursing and

Family (GEENF – "Grupo de Estudos em Enfermagem e Família", in Portuguese

language). University of São Paulo, Nursing School, São Paulo, Brazil.

E-mail: angelm@usp.br

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2018.34451

ABSTRACT

Objective: to evaluate the impact on nurses' attitudes of an educational intervention on Family Systems Nursing. Method: quasi-experimental study with 37 nurses working in the neonatal and pediatric context of a university hospital. The intervention stage, in December 2014, consisted of theoretical and practical training. Data were collected by self-completion of the scale "The Importance of Families in Nursing Care – Nurses' Attitudes" and were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney, Spearman Correlation Coefficient and Steel-Dwass-Critchlow-Fligner tests. Results: nurses who scored lower in the pre-intervention phase showed greatest positive difference after the educational intervention, and returned scores indicative of attitudes favorable to the inclusion of the families in care. Conclusion: after the educational intervention, positive impact was found on nurses' attitudes regarding the inclusion of families in nursing care.

Descriptors: Family nursing; Training; Attitude; Nurses, pediatric.

INTRODUCTION

Family Systems Nursing is a care perspective with focus on the relationship established between patient, family, and healthcare practitioners. According to this perspective, the family system is the object of care, and care is defined by the relationships established between the parties. Nurses' thoughts and attitudes should be centered on the interactions and reciprocity between family, illness, and the nurse1.

The care approach recommended by Family Systems Nursing requires the practitioner to adopt a broader point of view, beyond the individual/patient, to focus their assessment on family competences and strengths, and to develop skills for interviewing families, which often makes its implementation challenging in clinical practice2.

The growing international interest in a systematic approach to patient and family care, as the Family Systems Nursing's proposal, requires a special attention on how this knowledge must be directed to clinical practice, which includes transferring this knowledge to the practitioners who shall implement it. Knowledge transfer refers to a process intended to reduce the gaps between what is already known scientifically and the implementation of this knowledge in practice, in order to obtain better results for patients and families, as well as to improve productivity in health care systems.3,4

Researches on knowledge transfer related to Family Systems Nursing have been carried out since the beginning of the 21st century in countries such as Iceland and Canada, promoting the movement between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice.5 The results of recent researches have shown that the translation of knowledge, essentially through educational interventions based on this perspective, has a positive impact on nurses' attitudes regarding the importance they give to the inclusion of families in the care,6-10 as well as on the confidence, knowledge, and skills to interview and assist the families.8,9

The attitudes encompass affective, cognitive, and behavioral components.11 The applicability of Family Systems Nursing is directly influenced by the nurses' attitudes regarding the importance they give to including the families in the care.10 Therefore, it is essential to evaluate these attitudes, as they are a fundamental prerequisite for nurses to establish a care approach that focuses on the family, influencing the quality of the relationship established.12,13

Despite the promising results for patients, families, and nurses facing the implementation of Family Nursing, the transfer of this specific knowledge to nursing clinical practice is challenging, especially since this essentially relational approach requires a conceptual look at the family system and family interview skills, which often find obstacles to the implementation in the contexts of practice.2

In light of the above, this research used the following question to boost it: What is the impact of an educational intervention based on Family Systems Nursing on the nurses' attitudes related to the importance to include the families in the nursing care?

The study aimed at: Assessing the impact of an educational intervention based on Family Systems Nursing on the nurses' attitudes regarding the importance to include the families in the nursing care.

METHOD

A quasi-experimental intervention research was carried out using an interrupted time series design with a single group, without randomness, using pre and post-test, with a convenience sample. The study was carried out in a University Hospital (UH) located in the city of São Paulo, which practices have been reassessed to include the families in the care in some units of the pediatric and maternal-infant areas. Nurses working in Rooming-In, Nursery, Pediatrics, Pediatric Emergency Room, Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, and pediatric residents were invited to participate in the research. The inclusion criteria were: being a nurse in the units mentioned or being a pediatric nursing resident, having a minimum professional experience of six months, and having interest and availability to participate in the phases proposed by the study. The participants who did not complete the theoretical and practical phases (dramatization and/or interview with the family in the field) of the training were excluded.

Educational intervention

The educational intervention was a training composed of theoretical and practical phases with the primary goals of raising awareness among nurses to "think as family" and developing skills to interview the families. "Thinking as family" is defined as acknowledging that patients are always part of a family, and hence family members must always be considered in nursing care.9 Based on the perspective of Family Nursing, the Calgary Family Assessment and Intervention Models14 were chosen to support the training content. The theoretical phase took five years and included lectures, discussions, and group debates. The practical phase consisted of interview dramatization and/or interview with families in the clinical practice. The interview with the families in the clinical practice was optional, and only nurses who passed the theoretical phase could do it. An instrument referred to as "Guide for Family Care in Nursing Practice,"15 developed by the authors, was used in the practical phase in order to guide and record the interview process and to cooperate with the development of nursing skills.

The clinical practice was planned based on the concepts of coaching, role model, and mentorship, thus, for two weeks, one of the researchers monitored the assistance units, inviting the nurses who completed the theoretical stage to help her to interview a random family, or discussing the cases with those who interviewed the families by themselves. The participants who concluded the theoretical phase and one or both of the proposals of the practical phase were included in the study sample.

Measuring instrument

To evaluate the nurses' attitudes regarding the importance to include the families in nursing care, the instrument "Families Importance in Nursing Care –Nurses Attitudes (FINC-NA)" (Importância das Famílias nos Cuidados de Enfermagem – Atitudes dos Enfermeiros (IFCE-AE) in Portuguese language)16,17 was used in the pre and one-month post-intervention phases. It is a self-filling instrument composed of 26 items including three factors or subscales: Factor/Subscale 1: Family: conversational partner and coping resource (12 items); Factor/Subscale 2: Family: resource in nursing care (10 items); Factor/Subscale 3 Family: burden (4 items). The total IFCE-AE scale score ranges from 26 to 104. Higher scores in the total scale and in all subscales indicate attitudes of greater support to family inclusion in nursing care.

Data analysis

Data from the IFCE-AE instruments were tabulated in Microsoft Excel 2010, and subsequently exported to the database of the program Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22. The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests, the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test and the Spearman Correlation Coefficient, and the (post hoc) Steel-Dwass-Critchlow-Fligner test were used. The significance value of 5% (p≤0.05) was considered in order to compare the analyzed variables.

The total scale scores and quartiles and all subscales evidenced in the pre-intervention phase were used as passing scores to point out the participants whose scores indicated attitudes supporting or not the family involvement in nursing care. The participants with scores between quartile 1 and quartile 3 were considered attitudes supporting the participation of families in nursing care and participants with scores below the first quartile (q1)12 were considered attitudes that did not support families.

Ethical aspects

The research project was filed under number 29472414.2.0000.5392 in the Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Consideration (CAAE – "Certificado de Apresentação para Consideração Ética", in Portuguese language) and submitted to evaluation of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo's Nursing School and of the Research Ethics Committee of the co-participant Institution, being approved under number 657.118. Before the pre-intervention data collection, all nurses invited received information regarding the study and the ethical aspects, according to the National Health Council Resolution 466/2012, and those who chose to participate formalized their decision upon the signature of the Free and Informed Consent.

RESULTS

40 nurses began the training and 37 completed it. Of these, 23 nurses interviewed the families in the clinical field, of which 11 interviewed one family by themselves, 10 (ten) interviewed with the researcher's assistance, and 2 (two) interviewed two families, one by themselves and the other with the researcher.

With respect to filling the IFCE-AE scale, 37 nurses filled it in the pre-intervention phase, and 31 in the post-intervention phase. Of the 31 scales that returned in the post-intervention phase, it was not possible to find the correspondent person in the pre-intervention phase in four scales, hence, the valid sample for comparing the pre and post-intervention scores was of 27 individuals.

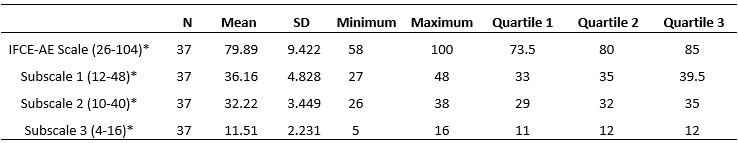

Table 1 shows the sample scores in the pre-intervention phase regarding the total IFCE-AE Scale and subscales, informing the nurses' attitudes who started the training about the importance to include the family in the nursing care and the passing scores considered pursuant to the quartiles provided. For the total IFCE-AE scale, which score may range from 26 to 104, an average of 79.89 (SD=9.422) was observed, with a score ranging from 58 (minimum) to 100 (maximum) among the participants. One half of them showed a score below 80 (below the group average) and 25% a score below 73.5 (quartile 1), indicating that one fourth of the nurses showed attitudes who did not support the family participation in nursing care.

Table 1:

Nurses' attitudes in the pre-intervention phase regarding the importance to

include the families in nursing care. São Paulo, SP, Brazil 2015. (n=37)

Note: Subscale 1 – Family: conversational partner and coping

resource. // Subscale 2 – Family: resource in nursing care. //

Subscale 3 – Family: burden *Possible punctuation range

In the pre-intervention phase, there was a statistically significant difference in the total IFCE-AE scale (p=0.037) and the Subscale 2 – "Family: resource in nursing care" (p=0.017) regarding the variable related to questions about the previous contact of the nurse with the content related to Family Nursing. It was verified that the nurses who had already had contact with some content related to this area of knowledge had higher average scores in the total IFCE-AE scale (81.22) and the subscale 2 "Family: resource in nursing care" (32.81) when compared to those who had no contact with anything related to this area of knowledge, which averaged 71.40 in the total IFCE-AE scale and 28.40 in the subscale 2 – "Family: resource in nursing care". There were no statistically significant differences for the subscale 1 – "Family: conversational partner and coping resource" (p = 0.064) and subscale 3 – "Family: burden" (p=0,111) with respect to this variable.

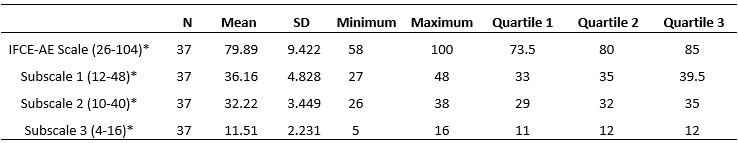

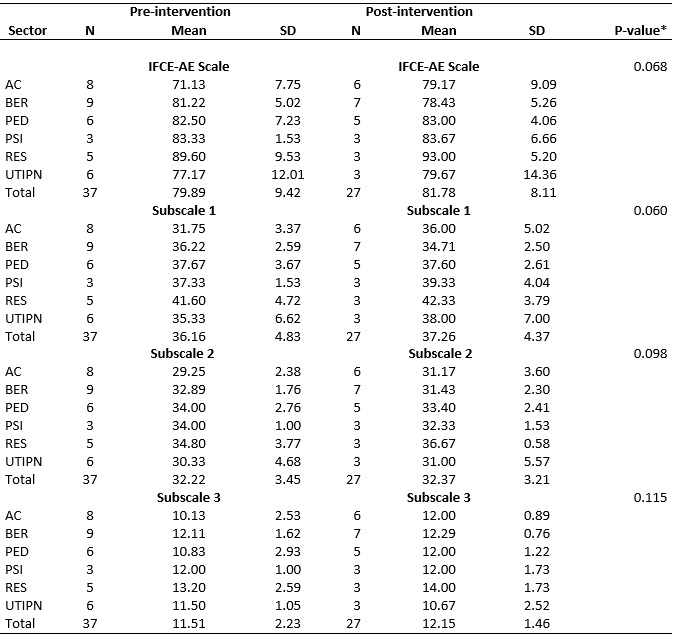

As evidenced in Table 2, nurses from the Rooming-In, who had pre-intervention scores indicating attitudes not supporting the inclusion of families in the care (71.13), were the ones that presented the greatest positive difference after the intervention, showing an average score indicating attitudes supporting the inclusion of families in nursing care.

The nurses who joined the group of pediatric residents, followed by the nurses of the pediatric emergency room, showed higher average score, pointing out attitudes supporting the families, both in the pre and post-intervention phases (Table 2).

Table 2:

Comparison of the total score of the IFCE-AE scale and the scores of

the pre and post-intervention subscales with the sector in which the

nurses work

. São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2015. (n=37)

Note: Rooming-In (AC); Nursery (BER); Pediatrics (PED); Pediatric Emergency

Room (PSI); Pediatric Residents (RES); Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive

Care Unit (UTINP).

Subscale 1 – Family: conversational partner and coping resource. // Subscale 2 – Family: resource in nursing care. // Subscale 3 -

Family: burden.

*Kruskal-Wallis test for pre and post-intervention difference.

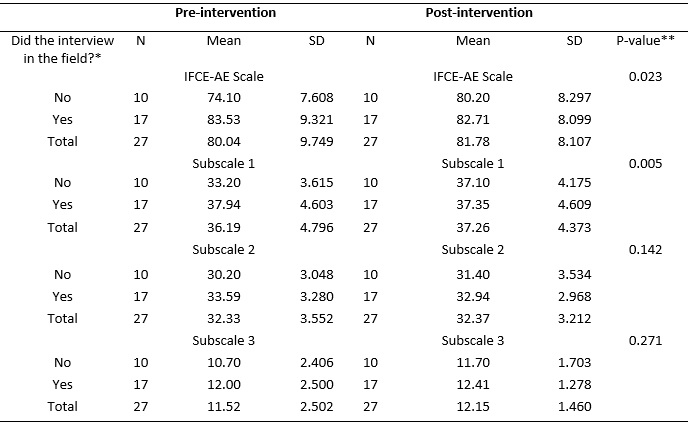

The interviews in the clinical practice with the families were the variable that indicated the statistically significant difference in the nurses' attitudes when the groups were compared in the pre and post-intervention phases. The difference was in the total IFCE-AE Scale (p = 0.023) and in the subscale 1- Family: conversational partner and coping resource (p=0.005) (Table 3).

With respect to total IFCE-AE Scale, those nurses who did not interview any family in the clinical practice showed a higher difference (6.10 more) between the score distribution in the pre (74.10) and post-intervention (80.20) phases than those who did it, and they virtually did not show any difference (0.82 less) in the pre (83.53) and post-intervention (82.71) phases (Table 3).

In comparison with subscale 1 – Family: conversational partner and coping resource, those nurses who did the interview with the families had a greater difference (3.90) in the distribution of pre (33.20) and post-intervention scores (37.10) than those who interviewed the families in the clinical field, who presented almost no difference (0.59 less) between the pre (37.94) and post-intervention (37.35) phases (Table 3).

Table 3:

Comparison of the total score of the IFCE-AE scale and the scores of

the pre and post-intervention subscales with the group of nurses who

participated or not in the interview in the clinical practice.

São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2015. (n=27)

Note: *Did the interview and used the proposed guide with any family in

his/her unit?

Subscale 1 – Family: conversational partner and coping resource. // Subscale 2 – Family: resource in nursing care. // Subscale 3 -

Family: burden.

** Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test for the pre and post-intervention difference.

* The results showed in the table regarding the nurses' interview in the

Clinical Practice relate only to the sample that answered to the IFCE-AE

Scale in the pre and post-intervention phases. These data do not reflect

the real number of nurses who participated or not in the practical phase of

the interview in the clinical field in the intervention phase.

According to Table 3, considering only the pre-intervention phase and those who filled the IFCE-AE scale in the pre and post-intervention phases, the nurses who did the interview in the clinical practice showed in the pre-intervention phase scores higher than those nurses who missed the interview with the families in the clinical practice. Regarding the total IFCE-AE scale, those who did the interview in the clinical practice showed an average score of 83.53 (SD=9.321) in the pre-intervention phase, whereas those who did not do the interview averaged 74.10 (SD=7,608). Thus, the nurses who did the interview in the clinical practice in the post-intervention phase started the training with scores higher than those nurses who missed the family interview phase in the clinical practice.

DISCUSSION

Regarding the nurses' attitudes on the importance they give to include the families in nursing care, there was a positive impact on the nurse's attitudes after the educational intervention. The main impact was on those nurses who had lower scores in the pre-intervention phase and who did not do the interview in the clinical practice. It is important to note that the nurses who participated in the practical stage in the clinical field were more open and available to interact and relate to the families, as they showed higher scores in the pre-intervention phase than those who chosen to skip the practical stage in the field and had lower scores, indicating attitudes that did not support the families' participation. The nurses who participated in the clinical practice and had already higher scores in the pre-intervention phase did not show any difference between the pre and post-intervention phases, as they already showed attitudes supporting the families.

Such evidence is relevant and endorsed by the literature, because when the transfer of knowledge is directed to include the families in the care context, the nurses' attitudes supporting the participation of families in nursing care promote a health care environment that facilitates the implementation of family nursing, since positive attitudes are an important premise for the nurse to open up, include families in the care, and relate to them.12

Nurses' attitudes regarding the importance to include families in nursing care had already been the object of a Brazilian study17 carried out in the same place, in the same units, and using the same instrument as this study, which indicated an average total IFCE-AE scale score of 82, higher than the pre-intervention phase of this study, whose initial score for the total IFCE-AE scale was 79.8. The average scores presented in the IFCE-AE scale of this study were similar to the scale of a study carried out in Portugal, which average score of the pediatric nurses was of 79.9, 18 and lower than those presented by two other studies with European nurses12,19 that showed an average score for the total IFCE-AE scale equal to 88.

A Swedish study12 showed a score corresponding to the first quartile of the IFCE-AE scale of 81, considerably higher than in the Brazilian studies, especially in the pre-intervention phase of this study, which was equal to 73.5. In the Brazilian study prior to this one, 12 the first quartile was equal to 77, that is, after three and a half years from one assessment to another, the average score of 25% of the nurses considerably decreased, evidencing the dynamic aspect of the analyzed concept.

The evaluation of the nurses' attitudes regarding the importance of the families in nursing care with respect to the variable "sector" in the pre-intervention phase of this study, as well as in the previous Brazilian study,17 indicated a statistically significant difference for the total IFCE-AE scale and for subscale 2 – "Family: resource in nursing care". The nurses in Rooming-In had the lowest average score among all other evaluated sectors, both for total IFCE-AE scale and subscale 2: "Family: resource in nursing care". The average score of the nurses in Rooming-In related to the total IFCE-AE scale in the previous study 17 was of 76, higher than in the pre-intervention phase of our study (71.1) and lower than the post-intervention phase (79.1). For subscale 2: "Family: resource in nursing care", the average score in the first study was of 30, being lower in the pre-intervention phase of this study, which average was 29.2. A Portuguese study found an average of 30.6 for this subscale.18

The nurses working in the Pediatric Emergency Room who participated in both national studies still have higher scores when compared to the other groups. In the first national study,17 nurses of the Pediatric Emergency Room had an average score equal to 87 for the total IFCE-AE scale and 35 for subscale 2: "Family: resource in nursing care", whereas, in this study, they had an average pre-intervention score equal to 83.3 for the total IFCE-AE scale and 34 for subscale 2: "Family: resource in nursing care", with no statistically significant difference in the post-intervention phase.

Regarding the variable that questioned the nurses' previous contact with the content related to Family Nursing, there was a statistically significant difference for the total IFCE-AE scale and subscale 2 – "Family: resource in nursing care", where nurses who had had contact with some content related to this area of knowledge showed higher scores in the pre-intervention phase of this study and in the previous Brazilian study, indicating attitudes of greater support to the inclusion of families in the care.17 This shows that the nurses' involvement with content related to this topic make them more sensible and open to the families.

In the European context, a study found a significant association between the nurse's educational level and the scores, and those with higher educational level showed higher scores, pointing out attitudes more positive to the families' participation in nursing care. It was also found an association between the age of the nurses and the scores, where the youngest had less positive attitudes in terms of perceiving the family as a dialogue partner and would more often perceived the families of the patients as a burden.19 Different from the European study, these associations were not statistically significant in this study. However, the resident nurses were the youngest in this study, and were the ones with higher scores in this study, showing that they had attitudes more favorable with respect to the families than the others.

An educational intervention study based on Family Systems Nursing carried out with nurses from a psychiatric unit in Iceland10 indicated an initial average (pre-intervention) score of 91.2 among female nurses and 86.5 among male nurses, being considerably higher than the initial average of our study, which was equal to 79.8. In the post-intervention phase of the Icelandic study, there was a statistically significant difference regarding only subscale 3: "Family: burden", where the score after the educative intervention showed that the nurses changed the way they thought about family as being a burden after they were trained, which was not evidenced in our study. A similar study carried out in surgical units of the same hospital did not find differences in the nurses' attitudes before and after the educational intervention.7

The short time between the intervention and data collection after the intervention and the fact that the nurses did not do the interview in the clinical field were limitations of the study. Another limitation may be attributed to the fact that the study was not carried out in a single institution; doing the intervention in other institutions may create different results, especially depending on the organizational culture. We agree that other researches are needed to explore the cultural and regional differences in the nurses' attitudes towards their role and attitudes to involve the families in nursing care.19

CONCLUSION

A positive impact on the nurses' attitudes regarding the importance they give to include the families in nursing care was verified after the educational intervention about Family Systems Nursing that integrated theoretical and practical phases. The nurses with attitudes that did not support the family inclusion in care in the pre-intervention phase were the ones with significantly increased score values indicating attitudes supporting the families after the training; however, they did not do the interview with the families in the clinical practice.

The nurses with higher score in the pre-intervention phase, that is, who had attitudes supporting the family inclusion in nursing care, were the ones who accepted to participate in the practical phase in the clinical field, showing that the nurses' positive attitudes with the families make it easier to transfer the knowledge to the clinical practice.

The successful actions showed in this study through the consolidation of this systematic process of training the nurses with respect to Family Systems Nursing may be reproduced in other academic or care institutions and, then, contribute to the progress of the knowledge and education of the nurses to provide Family Systems Nursing in the clinical practice.

REFERENCES

1.Bell JM. Family systems nursing: Re-examined. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2018 Apr 18]; 15(2):123–9. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840709335533 .

2.Duhamel F. Translating Knowledge From a Family Systems Approach to Clinical Practice: Insights From Knowledge Translation Research Experiences. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 4 de novembro de 2017; 23(4):461–87. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840717739030 .

3.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof [Internet]. 2006;26(1):13–24. Available at: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00005141-200626010-00003

4.Svavarsdottir EK, Tryggvadottir GB, Sigurdardottir AO. Knowledge Translation in Family Nursing: Does a Short-Term Therapeutic Conversation Intervention Benefit Families of Children and Adolescents in a Hospital Setting? Findings From the Landspitali University Hospital Family Nursing Implementation Project. J Fam Nurs. 2012;18(3):303–27.

5.Leahey M, Svavarsdottir EK. Implementing Family Nursing: How Do We Translate Knowledge Into Clinical Practice? J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 25 de novembro de 2009;15(4):445–60. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840709349070

6.Svavarsdottir EK, Sigurdardottir AO, Konradsdottir E, Stefansdottir A, Sveinbjarnardottir EK, Ketilsdottir A, et al. The Process of Translating Family Nursing Knowledge Into Clinical Practice. J Nurs Scholarsh [Internet]. janeiro de 2015;47(1):5–15. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jnu.12108

7.Blöndal K, Zoëga S, Hafsteinsdottir JE, Olafsdottir OA, Thorvardardottir AB, Hafsteinsdottir SA, et al. Attitudes of Registered and Licensed Practical Nurses About the Importance of Families in Surgical Hospital Units. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 15 de agosto de 2014;20(3):355–75. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840714542875

8.Eggenberger SK, Sanders M. A family nursing educational intervention supports nurses and families in an adult intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care [Internet]. novembro de 2016; 29(4):217–23. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1036731416300819

9.Broekema S, Luttik MLA, Steggerda GE, Paans W, Roodbol PF. Measuring Change in Nurses' Perceptions About Family Nursing Competency Following a 6-Day Educational Intervention. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 19 de novembro de 2018; 107484071881214. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840718812145

10. Sveinbjarnardottir EK, Svavarsdottir EK, Saveman BI. Nurses attitudes towards the importance of families in psychiatric care following an educational and training intervention program. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011; 18(10):895–903.

11.Altmann TK. Attitude: A Concept Analysis. Nurs Forum [Internet]. julho de 2008; 43(3):144–50. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00106.x

12. Benzein E, Johansson P, Årestedt KF, Saveman B-I. Nurses' Attitudes About the Importance of Families in Nursing Care. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 7 de maio de 2008; 14(2):162–80. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840708317058

13.Saveman B-I. Family Nursing Research for Practice: The Swedish Perspective. J Fam Nurs [Internet]. 9 de fevereiro de 2010;16(1):26–44. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1074840709360314

14. Wright LM, Leahey M. Nurses and families: A guide to family assessment and intervention. 6th ed. Philadelphia: F.A Davis Company; 2012.

15. Santos LG dos, Cruz AC, Mekitarian FFP, Angelo M. Family interview guide: strategy to develop skills in novice nurses. Rev Bras Enferm [Internet]. dezembro de 2017; 70(6):1129–36. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-71672017000601129&lng=en&tlng=en

16.Oliveira P da CM, Fernandes HI V, Vilar AISP, Figueiredo MH de JS, Ferreira MMSRS, Martinho MJCM, et al. Attitudes of nurses towards families: Validation of the scale Families' Importance in Nursing Care - Nurses Attitudes. Rev da Esc Enferm. 2011; 45(6):1331–7.

17. Angelo M, Cruz AC, Mekitarian FFP, Santos CC da S dos, Martinho MJCM, Martins MMFP da S. Nurses' attitudes regarding the importance of families in pediatric nursing care. Rev da Esc Enferm da USP [Internet]. agosto de 2014;48(spe):74–9. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0080-62342014000700074&lng=en&tlng=en

18. Fernandes C, Gomes J, Martins M, Gomes B, Gonçalves L. The Importance of Families in Nursing Care: Nurses' Attitudes in the Hospital Environment. Rev Enferm Ref [Internet]. 2015;IV Série(7):21–30. Available at: http://esenfc.pt/rr/index.php?module=rr&target=publicationDetails&pesquisa=&id_artigo=2547&id_revista=24&id_edicao=88

19. Luttik M, Goossens E, Ågren S, Jaarsma T, Mårtensson J, Thompson D, et al. Attitudes of nurses towards family involvement in the care for patients with cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs [Internet]. 2017;16(4):299–308. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1474515116663143