ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Socio-demographic profile of female adolescents in a street situation: analysis of sociocultural conditions

Lucia Helena Garcia PennaI; Joana Iabrudi Carinhanha II; Liana Viana RibeiroIII; Helena Maria Vianna GraçaIV; Caroline dos Santos MarquesV

I

Obstetrical Nurse. PhD. Professor of the Postgraduate Program in Nursing of

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State University).

Brazil. E-mail: luciapenna@terra.com.br

II

Obstetrical Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Adjunct Professor at the School of

Nursing of Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State

University). Brazil E-mail: iabrudi@yahoo.com

III

Nurse. PhD student of the Postgraduate Program in Nursing of Universidade

do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State University). Brazil.

E-mail: liana_vian@hotmail.com

IV

Nurse. Msc student of the Postgraduate Program in Nursing of Universidade

do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State University). Brazil.

E-mail: lena_mvianna@gmail.com

V

Nurse. Msc student of the Postgraduate Program in Nursing of Universidade

do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro State University). Brazil.

E-mail: carolmarquesenf@gmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2017.29603

ABSTRACT

Objectives: to analyze the social, economic and demographic profile of female adolescents in a street situation, from the standpoint of socio-cultural conditions. Methodology: this quantitative study of 21 adolescent women with experience of living on the street, in care at two of Rio de Janeiro's municipal shelters. Data were produced from interviews with objective questions to characterize a social, economic and demographic profile, and were subjected to statistical analysis by calculating absolute and percentage frequencies. Results: most of the adolescents were black or brown, had little schooling, and were from poor communities; most had lived away from their families for more than one year and had been institutionalized several times; their guardians had little schooling, and were un- or under-employed or involved in illegal or criminal activities. Conclusion: the data reflect the group's historical roots and its reproduction of parental patterns, and highlight the intergenerational precarity. The long histories of removal from the family indicate the extent to which family ties are fragmentary, and evidence precarious economic and psycho-affective conditions and the need for preventive interventions.

Keywords: Homeless youth; women's health; nursing; public health.

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of the female adolescent in street situation is a serious social issue. The context of family instability associated with structural economic instability and the lack of support by public institutions compromise the maintenance of significant socio-family ties, inciting children and adolescents to follow paths that lead them away from the family environment. This path may culminate in taking the streets as a space for survival, causing such ties to be broken and reducing any eventual chances of they being employed – which characterizes a disaffiliation process.

These young girls experience a feeling of not belonging, whose possibility of social insertion mostly takes place through violence – here understood as a resistance against an instituted socio-political and economic system that disregards and denies their rights, prevents the inclusion of all persons, discriminates and sets them apart from society from the very beginning in a stigmatization process1,2. In the case of the female adolescents, in addition, there is the prostitution and pregnancy in this phase and within this context, which are usually condemned. Thus, the presence of the female adolescent in the streets causes the other (civilians) to feel some discomfort and guilt about it; that is why they have to be eliminated or, at least, concealed, besides blaming them (and, most of the times, accusing them) for the violent acts in the city streets, as well as for the iniquities they reflect and accentuate in a strikingly noticeable manner3,4.

On the other side, the separation from family is, today, a violation of the children and adolescents' rights5-7, although this is a historical reality that is experienced in many Brazilian families. The interest to understanding such complexity and being able to assist in preventive interventions that promote health have been a proposal of governmental actions8,9. However, in practice, such phenomenon has remained separated from the healthcare network, being a challenge to the principles guiding the Unified Health System (SUS) – universality, equality, integrality10.

The issue of the female adolescent in street situation, considering the origin of this disaffiliation process – separation from family 4,11, requires the search for answers to this social and public health problem, given its complexity and impact on the physical and mental health of many female adolescents and families.

Seeking for signs on the life conditions that precede leaving home, at first, this work aims to analyze the socio-demographic profile of the female adolescents with experience of living in the streets, from the perspective of the sociocultural conditions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The history of adolescence in street situation dates back to the time of colonization where the urbanization process made the situation of poor children and those considered as illegitimate worse, who were rejected or abandoned in the streets, making it necessary the organization of institutions in support of such children and young people and, subsequently, of children of slave mothers. From that time on, the abandoned and poor childhood and youth have been watched and controlled based on the precepts of protecting them from the risk that they might become dangerous or criminals, being sometimes classified as dangerous and other times as in danger and, therefore, justifying repressive measures to prevent them from being corrupted by the pernicious social environment 5,12.

The first national census of street children and adolescents, which was carried out in 2010, identified 23,973 children and adolescents living in street situation, and they are mostly in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro 13. Adolescents in street situation are only a small portion, more visible and threatening, of a large part of the young population that lives with their parents under very little favorable conditions 14.

National4,5 and international15,16 contexts reveal that the interrelationship among poverty, violence, and family instability are the primary reasons for separation from family for adolescents. However, families cannot be solely blamed for not having managed to protect and fostered the healthy development of their members as socially expected, as they are inserted in a neoliberal scenario that weakens employment and socio-family relationships, results in lack of access to education, health care, housing, leisure, and culture2,10,17. The higher the socioeconomic inequality is, the higher the vulnerability of the families, which significantly increases the number of people leaving their homes to live in the streets.

The number of young people in street situation consists mostly of the male sex, which reflects the gender asymmetries, from which the boys are encouraged to dominate the public space, using the streets for working or having fun, while the girls must remain restricted to the private life, doing housework and taking care of younger children18,19, reproducing a logic that makes women to accept situations of abuse or exploitation. In this regard, the female group is of qualitative importance, given the particulars of social and health vulnerability, with an emphasis on unplanned pregnancy; sexual exploitation and abuse; submission to the partner for protection or affection; high rate of sexually transmitted infections (STI's); abusive use of drugs as a consequence or cause; low self-esteem; higher impact of stressful events, mainly those related to domestic or sexual violence4,18,20,21.

Literature has highlighted that the experience of living in the streets has negative effects on the development of children and adolescents; however, the internal and external resources are preserved in order to overcome so many adversities 14,22. It is considered, also, despite the vulnerabilities involved in living in the streets, that such space aggregates positive affections, besides providing an alternative to the previous life situation that showed some potentially harmful vulnerability and risks18.

On the other side, studies have4,22-24 identified the difficulties faced by the institutional shelter services in providing the adequate care to children and adolescents, which largely consist of new violence situations, mainly due to the behaviors shaped by the traditional logic to restrain any deviation. However, they reported successful experiences of institutional care, which shows that institutionalization shows itself as an important strategy for supporting and sheltering young people in street situation, whenever it is well-equipped and -qualified.

METHOD

This is a descriptive study with a quantitative approach, having been carried out with 21 female adolescents who have experienced living in the streets and were then sheltered at two units of the shelter network for adolescents in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro (Special Protection Department of the Municipal Social Assistance Department – SMAS/RJ), located at the north and south side of the city, from March 2013 to May 2014.

After an initial time of reciprocal approach and recognition, and after the survey and its goals were made explicit, the female adolescents being taken care of were invited to participate in the study through an interview with objective questions of characterization of the socioeconomic and demographic profile of the respondents. The variables addressed were: age, skin color, education level, employment, length of time on the streets, current length of time under institutional care, history of previous care, person responsible for raising the adolescent, education level of the responsible persons, occupation of the responsible persons,

The interviews were one-on-one encounters and carried out in a private place at the shelter. Their participation was validated through the joint signature, by the management of each shelter unit (the then legal responsible persons), of the Informed Consent Form, in compliance with the ethical principles of Resolution no. 466, of 2012, on research involving human beings. It is worth highlighting that the study was previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee (COEP) of UERJ, under protocol number 253,927 and CAAE number 04252112.4.0000.5282, as well as by the Social Assistance Policy Qualification Center (SMAS/RJ), as this is the sector in charge of organizing research to be conducted by external institutions in the services and programs of SMAS/RJ.

The data so produced was then subjected to statistical analysis with calculation of the absolute (f) and percentage (%) frequencies, and interpreted according to the existing literature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

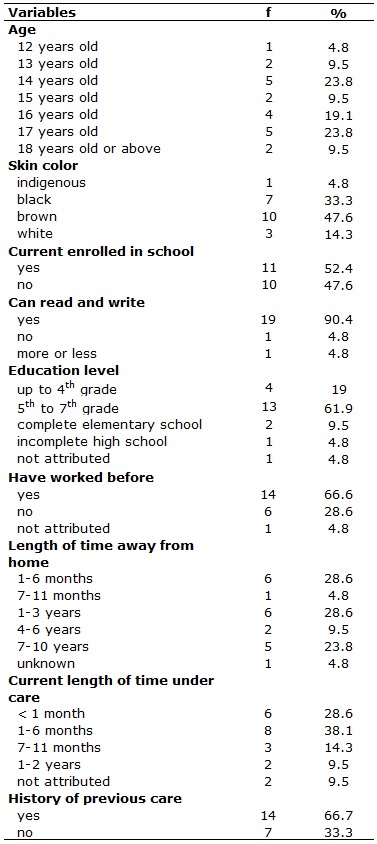

Table 1 shows the main variables of the socioeconomic and demographic profile of the female adolescents being studied. Their age ranged from 12 to 18 years old, and most of them reported to be from 16 to 18 years old (52.4%). Regarding skin color, there was predominance of adolescents who said to be brown (47.6%) or black (33.3%). In the national survey of children and adolescents at care service units5, among those being taken care of with a track record of living in the streets, there is also a higher number of young people in this age group and with black or brown skin color.

Only 11 female adolescents were attending to school then (52.4%). Furthermore, 17 adolescents (80.9%) were enrolled in the elementary school (up to the 7th grade) and were above 12 years old; therefore, it is found that a significant portion of them showed an age/grade discrepancy, and one adolescent (4.8%) said she cannot read nor write, and other (4.8%) can do it more or less. This data is similar to that found in the national survey5, which further revealed lower access to education by children and adolescents being under institutional care as compared to the rest of the child and adolescent population in Brazil. Notwithstanding the difficulties, the literature4,22 shows that, particularly regarding these girls, the study represents the possibility of changing such reality and creating a better life project.

TABLE 1

: Socioeconomic and demographic variables of the female adolescents. Rio de

Janeiro, RJ, 2014. (n=21)

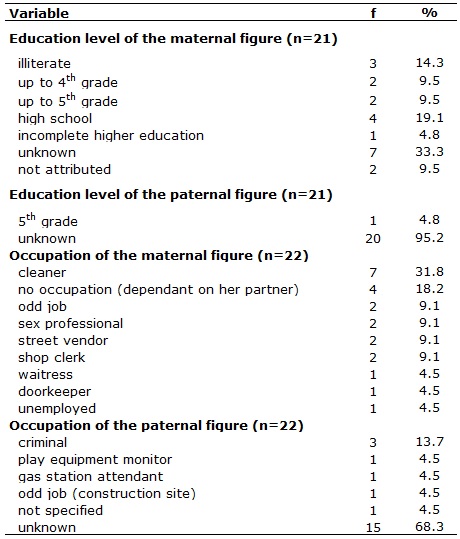

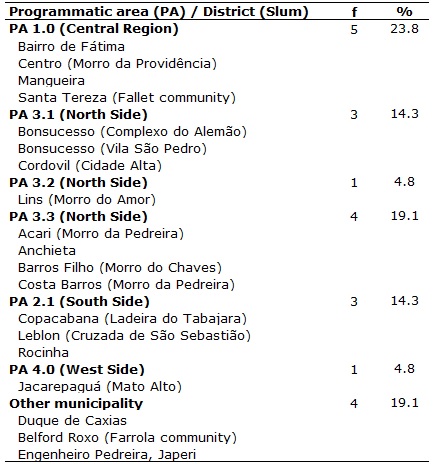

The female adolescents being surveyed are from poor communities in several regions of the city, mainly, in the central (23.8%) and north (38.2%) region, and only 4 among them are from other municipalities (19.1%), as shown in Table 2. The communities referred to by the adolescents are slums, which show the lowest rates of social development, as well as the highest rates of criminality (homicide, robbery, theft) in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro25,26. These are spaces that are organized at the margin of the State laws and rules; however, they are legitimated by the power of the organized crime, producing an "outskirtization" culture marked by violence4.

TABLE 2:

Education level and occupation of the persons responsible for the female

adolescents. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 2014.

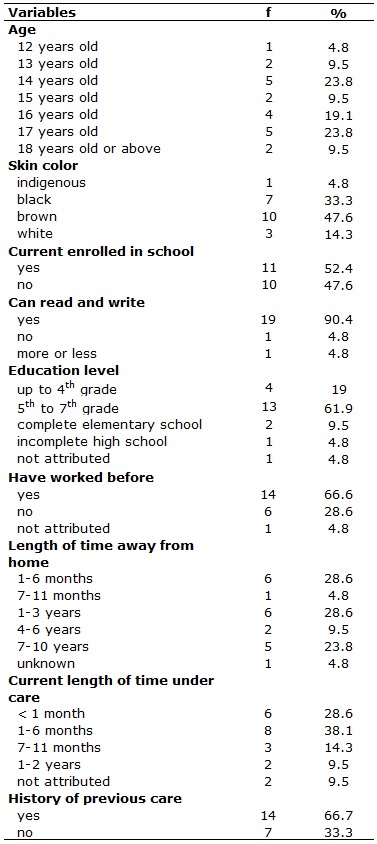

The female adolescents are from families that live in very poor and even miserable conditions, whose responsible persons have low education level in addition to a weak employment relationship (unemployment or underemployment) or the involvement in illegal/criminal activities, as shown in Table 3. Most of the mothers – 7 (33.3%) – attended school only up to the 5th grade, and two of them (9.5%) are illiterate; however, 4 (19.1%) among them attended up to high school. The low education level also appears when a significant portion of the adolescents is not able to provide such information regarding their mother (33.3%), mainly regarding their father (95.2%).

The poor relationship of the responsible persons with employment (unemployment/underemployment) is shown next, according to Table 3. Regarding the maternal figure, 17 (77.2%) mothers are underemployed (cleaner, doorkeeper, waitress, street vendors, odd job and prostitute), 4 (18.2%) have no occupation, remaining as dependants on their partner, and 1 (4.5%) is unemployed. The paternal figure, whenever present (15 adolescents cannot inform their father's occupation), also shows weak employment conditions (work in construction sites, gas station attendant, and odd jobs) – 3 (13.7%) – or is involved in criminal activities and/or drug dealing – 3 (13.7%).

Moreover, 13 (61.9%) adolescents say their mother is the responsible person for raising them, 7 (33.3%) have other maternal figures (aunt, grandmother) assuming such responsibility, and only one (4.8%) reports to have been raised by both parents.

TABLE 3:

Region of the community of origin of the female adolescents. Rio de

Janeiro, RJ, 2014. (n=21)

This data shows that the female adolescents being surveyed make up the group of the mother-headed single-parent families and, therefore, they are likely the poorest, this being also a reason for seeking institutional care 27. The daily needs and activities of such families involve a circuit that extends itself across space, drawing lines of mutual help and outlining possibilities of configuration and social values other than the traditional pattern of nuclear family. These are families that do not fit in the hegemonic model, so they are likely seen as dysfunctional and held responsible for the failed development of their children – which, for the healthcare area, may be harmful insofar as the lack of knowledge or undervaluation of the family strategies may imply restricted, limited interventions that do not meet their purpose, nor effectively solve the problems experienced by such families27-29.

As a result of having trouble making ends meet, the female adolescents being studied report poor housing, food, and hygiene conditions. Such situation becomes worse due to the numerous family composition, either resulting from family rearrangements or not. This is such that extreme conditions such as going hungry are often reported.

In order to organize the household affairs, some adolescents referred to the responsibility for the housework (washing, cleaning, cooking) and taking care of their siblings.

On the other side, most of the female adolescents – 14 (66.6%) – have reported to already have performed paid work before and/or after having left home, as shown in Table 1. In a diverse manner, they report work activities developed in the streets (street selling, windscreen washing, shoe shining, prostitution) – 9 (34.6%) – and paid activities related to housework or other typically feminine occupations (babysitter, cleaning assistant, elderly caretaker, hairdresser assistant, seamstress, car wash assistant, play equipment monitor, lunchbox delivery girl, shop clerk) – 14 (53.8%). Some adolescents – 3 (11.5%) – also mention the experience of attending a professionalizing training held by the shelter. A study carried out with adolescents in street situation reveals that, on one side, the reasons for early work are the need to supplement the family income, the need to follow up the adult person or make a subsistence living, and, on the other side, the search for work and income fosters their motivation to go to the streets13.

A majority (61.9%) of the adolescents interviewed have lived outside their homes for more than one year, and a significant portion (23.8%) have been far from family for more than seven years, as shown in Table 1. Throughout this time, 14 (66.7%) female adolescents reported to have been sheltered on previous occasions at the shelter network, and, currently, 14 (66.6%) among them have been sheltered for less than 6 months. This result is consistent with national and international data5,16, in which it was found that nearly half of such population has lived on the streets for more than one year. Historically, the disaffiliated adolescence, in Brazil, had its institutionalization born from a practice the purpose of which was to restrain the deviation, which is characterized as discriminatory and stigmatizing21, as previously said.

The track record of successive times at the institutional shelter network referred to by the respondents shows, on one side, the protection system's difficult in promoting family reinsertion in an effective way, as the stigma of these adolescents is so deep-rooted in our culture that the shelter professionals themselves are reluctant to change such perception and such authoritarian posture toward poor young people, disregarding their needs and points of view, so the adolescent with problems, rather than the individual with rights, remains the object of attention29. On the other side, there is the challenge faced by the adolescent herself to adapt to the institutional rules5, which attempt to fit the youth into an ideal pattern of good behavior. Despite the effort made toward a caring dialogue, there is still many barriers to overcoming abandon and establishing quality care that fosters welcoming and psycho-affective support these young girls need4,22-24,30.

The female adolescents in this study are, mostly, black, from popular

classes, do not fit in the good student model (good school performance),

characterizing a profile that is largely spread as a problem and brings the

marks that are sufficient for creating the stigma of juvenile delinquent

and helpless minor. Therefore, they may be seen as inadequate to the

hegemonic capitalist and health system.

The family and community contexts reported by the adolescents evidence the condition of psychosocial vulnerability in which they develop from the association between poverty (which, by itself, is not a synonym to vulnerability, yet the risks are higher to such class) and other factors that make dialogue difficult and stir up tension (such as low education level, precarious work, involvement with drugs, violent community environment).

Living under exploitation and iniquity conditions creates individuals whose social ties are increasingly weakened, driving children and adolescents away from school and compelling them to work early in life in order to struggle for their survival, besides depriving them from adequate physical and mental development due to the lack of food and strong affective ties, among other needs31. This entails consequences for the future of these adolescents, who, according to the literature21, 32, aim at establishing a family of their own; however, most of the times, they do not see the possibility of building an affective relationship with their children, due to their history of life with weakened or broken family ties.

Such perspective is reinforced by the data produced that evidences the repeated patterns and values among generations through the association of low education level with scant employment opportunities both for the adolescents and their mothers.

CONCLUSION

The data shown reflects the historical roots of the group: the adolescents are black, poor, have low education level or no education at all, are engaged in subaltern activities and/or socially condemned for supporting themselves financially, which shapes a stigmatized image. It is worth mentioning also, based on the family information, that these young girls reproduce the parental pattern, which highlights the intergenerational precariousness established by an unfair and unequal socioeconomic order that is gradually failing to provide the basic conditions for a great number of Brazilian families to live with some dignity. In addition, the long track record of separation from family, alternating between a life on the streets and at the institutions that provide shelter and care, shows the dimension of the weakening of family ties, giving signs not only of economic, but also psycho-affective precariousness.

In face of the destabilization of the family and community context shown,

in one way or another, the adolescents experience and learn a culture of

living that is precarious and violent, which contributes to their

disaffiliation, violation of their rights, and tends to make a future with

dignity and citizenship impracticable.

The limitations of this study concern its scope, which does not allow generalizations and limits a deeper look into the issues involved in the phenomenon of the female adolescent in street situation. Some aspects of the conditions of life of these young girls were raised, which provide evidences of the disaffiliation process they have experienced and demand preventive actions towards leaving home. However, no examination was made of the practices, relationships, and representations that shape such family daily life, which suggests the need for more studies that may contribute to corroborating the theoretical-scientific foundations that guide the behavior in providing assistance to the female adolescents and their families, as well as in ensuring their rights.

REFERENCES

1.Carinhanha JI, Leite LC, Penna LHG. "Minha arma é a mão": a violência como forma de resistência. In: Leite LC, Leite MED, Botelho AP, organizadoras. Juventude, desafiliação e violência. Rio de Janeiro : Contra-capa; 2008. p. 141-54.

2.Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome (Br). Política Nacional para Inclusão Social da População em Situação de Rua. Brasília (DF): Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome; 2008.

3.Penna LHG, Carinhanha JI, Rodrigues RF. Violência vivenciada pelas adolescentes em situação de rua na ótica dos profissionais cuidadores do abrigo. Rev eletrônica enferm. 2010 [cited in dez 1 2016]. 12(2):301-7. Available in: http://www.fen.ufg.br/revista/v12/n2/v12n2a11.htm .

4.Carinhanha JI, Penna LHG. Violência vivenciada pelas adolescentes acolhidas em instituição de abrigamento. Texto contexto-enferm. 2012; 21(1).

5.Assis SG, Farias LOP, organizadoras. Levantamento nacional das crianças e adolescentes em serviço de acolhimento. São Paulo : Hucitec; 2013.

6.Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos. Plano Nacional de Promoção, Proteção e Defesa do Direito de Crianças e Adolescentes à Convivência Familiar e Comunitária. Brasília (DF): Conselho Nacional de Assistência Social; 2006.

7.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção em Saúde. Diretrizes nacionais para a atenção integral à saúde de adolescentes e jovens na promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2010.

8.Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. Política Nacional para Inclusão Social da População em Situação de Rua. Brasília (DF): Conselho Nacional de Assistência Social; 2008.

9.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Política Nacional de Atenção Básica. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2012.

10.Paiva IKS, Lira CDG, Justino JMR, Miranda MGO, Saraiva AKM. Direito à saúde da população em situação de rua: reflexões sobre a problemática. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2016; 21(8):2595-606.

11.Marchi JA, Carreira L, Salci MA. Uma casa sem teto: influência da família na vida das pessoas em situação de rua. Ciênc cuidado saúde. 2013;12(4):640-7.

12.Patias ND, Siqueira AC, Dell'Aglio DD. Imagens sociais de crianças e adolescentes institucionalizados e suas famílias. Psicol soc. 2017; 29(e131636):1-11.

13.Silva BK, Bezerra WC, Ribeiro MC. Entre a casa e a rua: a percepção de adolescentes em situação de rua. Rev Ter Ocup Univ São Paulo. 2017; 28(1):100-9.

14. Morais NA, Raffaelli M, Koller SH. Adolescentes em situação de vulnerabilidade social e o continuum risco-proteção. Avances Psicol Latino-am. 2012; 30(1):118-35.

15. Reza MH. Poverty, violence, and family disorganization: three "Hydras" and their role in children's street movement in Bangladesh. Child Abuse Negl . 2016; 55(5 2016):62-72.

16.Cumber SN, Tsoka-Gwegweni JM. Characteristics of street children in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 2016;8(1):1-9.

17.Santos JR, Julião CH. O enfrentamento da situação de vulnerabilidade dos adolescentes em uma instituição de atenção social. REFACS. 2016; 4(1):33-9.

18.Lima RFF, Morais NA. Fatores associados ao bem-estar subjetivo de crianças e adolescentes em situação de rua. Psico. 2016; 47(1): 24-34.

19.Oliveira MAF, Gonçalves RMDA, Claro HG, Tarifa RR, Nakahara T, Bosque RM, et al. Perfil das crianças e adolescentes em situação de rua usuários de drogas. Rev enferm UFPE on line. 2016; 10(2):475-84.

20.Antoni C, Munhós AAR. As violências institucional e estrutural vivenciadas por moradoras de rua. Psicol em est. 2016; 21(4):641-51.

21.Penna LHG, Rodrigues RF, Ribeiro LV, Paes MV, Guedes CR. Sexualidade das adolescentes em situação de acolhimento: contexto de vulnerabilidade para DST. Rev enferm UERJ. 2015; 23(4):507-12.

22.Ferreira VVF, Littig PMCB, Vescovi RGL. Crianças e adolescentes abrigados: perspectiva de futuro após situação de rua. Psicol soc. 2014; 26(1):165-74.

23.Zappe JG, Dell'Aglio DD. Variáveis pessoais e contextuais associadas a comportamentos de risco em adolescentes. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2016; 65(1):44-52.

24.Morais NA, Koller SH. Um estudo com egressos de instituições para crianças em situação de rua: percepção acerca da situação atual de vida e do atendimento recebido. Estudos Psicol. 2012; 17(3):405-12.

25.Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos. Secretaria Municipal da Casa Civil (RJ). Homicídio doloso, roubo a transeunte, roubo de veículos e furto de veículos segundo Áreas Integradas de Segurança Pública [...] - 2004 a jun 2014. Rio de Janeiro: IPP; 2014.

26.Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos. Secretaria Municipal da Casa Civil (RJ). Índice de desenvolvimento social: IDS por AP, RP, RA, bairro e favela – 2000 a 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IPP;2010 [cited in nov 22 2014]. Available in: http://www.armazemdedados.rio.rj.gov.br/arquivos/2248_ids_2000_2010_ap_rp_ra_bairro_favela.XLS .

27.Brito CO, Rosa EM, Trindade ZA. O processo de reinserção familiar sob a ótica das equipes técnicas das instituições de acolhimento. Temas psicol. 2014; 22(2):401-13.

28.Carinhanha JI, Penna LHG, Oliveira DC. Representações sociais sobre famílias em situação de vulnerabilidade: uma revisão da literatura. Rev enferm UERJ. 2014; 22(4):565-70.

29.Patias ND, Siqueira AC, Dell'Aglio DD. Imagens sociais de crianças e adolescentes institucionalizados e suas famílias. Psicol soc. 2017; 29(e131636):1-11.

30.Penna LHG, Carinhanha JI, Leite LC. The educative practice of professional caregivers at shelters: coping with violence lived by female adolescents. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2009; 17(6):981-7.

31.Santana RP, Santana JSS. Violência contra criança e adolescente na percepção dos profissionais de saúde. Rev enferm UERJ. 2016; 24(4):1-6.

32.Penna LHG, Carinhanha JI, Martins VV, Fernandes GS. A maternidade no contexto de abrigamento: concepções das adolescentes abrigadas. Rev esc enferm USP. 2012; 46(3):544-8.