ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Peripherally inserted central catheter: practics of nursing team in the neonatal intensive care

Nataly Barbosa Alves BorghesanI; Marcela de Oliveira DemittoII; Luciana Mara Monti FonsecaIII; Carlos Alexandre Molena FernandesIV; Regina Gema Santini CostenaroV; Ieda Harumi HigarashiVI

I

Nurse. Master in Nursing from the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Paraná,

Brazil. E-mail: natalyalves@hotmail.com

II

Nurse. PhD in Nursing from the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Paraná,

Brazil. E-mail: mar_demitto@hotmail.com

III

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Associate Professor, Universidade de São Paulo.

Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: lumonti@eerp.usp.br

IV

Physical educator. PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences. Adjunct Professor at the

Universidade Estadual do Paraná. Brazil. E-mail: carlosmolena126@gmail.com

V

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Adjunct Professor of Nursing and Psychology Courses

at the Centro Universitário Franciscano. Parana Brazil. E-mail: reginacostenaro@gmail.com

VI

Nurse. PhD in Education. Coordinator of the Graduate Program in Nursing of

the Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Paraná, Brazil, E-mail: ieda1618@gmail.com

VII

Article extracted from the dissertation thesis: Peripherally inserted

central catheter (PICC): nursing team practices in neonatal intensive care.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2017.28143

ABSTRACT

Objective: to describe the application profile of the peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in the health care reality at Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Method: observational and descriptive study with quantitative approach, using a convenience sample of 47 PICC installed in 33 newborn, in the NICU of a university hospital in the Southern of Brazil. Results: most newborns were premature (72.7%), males (52.0%) and with ess than 2,500g (72.7%). Most of devices have been installed in the first three days of life (59.6%) with an average of 3.7 venipunctures, being the left upper limb (44.2%) the most most accessed. Almost half of devices had intracardiac as first location (48.8%) and were not removed electively (48.8%). Conclusion: the study pointed that the profile of patients using PICC in the studierd unit is similar to literature, and there are problems related to its insertion and mantenance.

Keywords: Neonatal nursing, catheterization, central venous, intensive care units, neonatal, nursing care.

INTRODUCTION

The peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) is a long flexible intravenous device, inserted through a peripheral vein puncture, which extends with the help of blood flow to the central location, i.e., the superior vena cava (SVC), or cavoatrial junction, if inserted by the upper limbs; and inferior vena cava (IVC), if inserted by the lower limbs1-4.

The PICC has been widely used in newborns (NB) due to the ease of insertion, for a prolonged period of time, besides allowing the safe infusion of irritant, vesicant and hyperosmolar solutions1,5. Its use is associated with a lower incidence of morbidity and mortality compared to other central venous accesses, as well as a lower risk for sepsis and pneumothorax1,2,6.

Although PICC has advantages that overlap with other central devices, studies have shown technical flaws for the insertion and maintenance of this device, which, in most cases, lead to withdrawal of PICC before the end of treatment, with or without injuries to the NB1,7.

In this sense, the present study aimed to outline the profile of indication and use of PICC in the care reality of the intensive care unit (NICU) of a university hospital in southern Brazil.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The PICC began to be used in Brazil from the 1990s, and nurses became the professionals most involved in the installation and maintenance of this device1,3,5.

It is, therefore, a technological care carried out by nurses, which provides the neonate with numerous benefits, such as the optimization of intravenous care without discontinuation of treatment; prevention of phlebitis due to extravasation; preservation of the peripheral venous system; stress reduction of the nursing team and the NB due to venous punctures1-3,5.

Although it has many advantages, this device maintenance also requires special care that demand attention and which, when neglected, can cause withdrawal of the device before the end of treatment. Thus, nursing practices are of paramount importance to ensure the safety of the newborn during the process of insertion, maintenance and removal of PICC8.

The procedure to install the PICC should be done when the venous network is still preserved, since the presence of edema, erythema, hematoma, or cutaneous lesion caused by previous venous punctures makes the catheter progression difficult9,10. The process for installing the PICC should occur at the bedside and with the maximum barrier technique. Other care to be taken in the insertion is the cardiac monitoring and pain management of the NB11.

In Brazil, the most commonly used technique for PICC insertion is the Blind Insertion Technique, which consists of measuring the catheter extension needed to reach the central location, performing venous puncture with an introducer and progressing throughout the length of the measured catheter. After this, the nurse performs a dressing and confirms the placement by X-ray examination11,12.

Maintaining the PICC requires attention. It is recommended that, in pediatric patients, dressing change should be performed only if it is lifting off, presenting dirt, moisture or bleeding, and there is no fixed time limit, since in pediatrics the risk of PICC displacement is greater than the benefit of exchanging it13. The preparation of the dressing is an exclusive activity of the nurse who received training, since this professional will be able to identify possible complications, presenting technical ability to prevent displacement and infection of the PICC through manipulation14.

The permeabilization with physiological serum should occur before and after the infusion of medications and every 6 hours to avoid obstruction. The use of syringes with a volume equal to or greater than 10 milliliters is indicated as lower volumes may cause rupture and embolism of the catheter lumen1,11.

Preventive measures should be adopted for catheter-related bloodstream infection (BSI)1,13, such as: maximum barrier in the insertion, sanitizing hands before and after the manipulation of the PICC; disinfection of the connections and hub with 70% alcohol before infusion of any solution; periodically replacing the infusion system (set, Y-connector) according to the routine established by the manufacturer or the unit; protecting the PICC and connections during bathing and removing the PICC as soon as it is no longer needed13,15,16.

The early identification of complications by the nurse is extremely important, and this professional should periodically observe the ostium of the catheter insertion in order to identify the presence of redness, secretion and signs of dislocation. They should also be alert to hyperthermia, phlebitis, cellulitis as well as fracture and obstruction of the device1,7,11.

Routine replacement of the PICC in order to prevent catheter-related BSI is not recommended, nor its removal solely because of fever13,17. Clinical judgment should be used to assess the likelihood of infection in other site11,17. Removal of the device may occur due to termination of therapy; inadequate positioning; presence of inflammatory signs at the insertion site or along the vein pathway; thrombosis in the access limb; fever or hypothermia with no other apparent infection focus; breakage or rupture; irreversible occlusion; extravasation of solutions or presence of infectious or inflammatory focus14,18. It is worth emphasizing the need to inspect the integrity of the tip of the PICC in the act of removal and check whether the length removed is compatible with that inserted.

METHOD

This is an observational, descriptive, quantitative study with a convenience sample composed of 47 PICCs inserted in infants hospitalized in a medium-sized university hospital, located in the South of Brazil. The institution has 10 beds intended for the care of sick NBs, six of which are in NICUs and four in semi-intensive unit (SIU).

Data were collected from January to August 2015. Inclusion criteria were as NBs admitted to the NICU and SIU during the referred period and who had undergone PICC insertion between 7 a.m. and 12 p.m.

Data regarding the PICC insertion procedure were collected through direct systematic observation. For this purpose, an Observation Script was used, which was prepared by the researcher himself and submitted to evaluation by a panel of experts, composed of PhD nurses with experience in the area. The data necessary for the characterization of the newborn and withdrawal of the PICC were obtained by consulting the records of the newborns and the PICC procedure record book of the sector.

The variables investigated were: gender, type of delivery, gestational age, birth weight, weight classification, Apgar score, medical diagnosis, PICC indication, number of procedures by NB, type of catheter inserted, use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures for pain control, days of life at insertion date, success at insertion, frequency of punctures, insertion veins, insertion segment, catheter positioning, catheter traction, radiography after traction, catheter withdrawal.

In the studied unit, the PICC insertion procedure is divided by schedules, in which each shift is responsible for two beds, but changes may occur. Of the 11 nurses who compose the staff, nine are qualified to insert the PICC.

As a way of guaranteeing the rigor of the research and facilitating the data collection, a single researcher made the observations. He was contacted by telephone by the NICU team to inform him that there would be a PICC insertion procedure. He, in turn, would came to the unit to make the observation.

The data were analyzed through descriptive statistics and presented in the form of tables.

The study was approved by the Standing Committee on Ethics in Research involving Human Beings of the State University of Maringá (COPEP/UEM), under the opinion number 919.277/2014 and Approval Code number 38822214.5.0000.0104. We requested the exemption of the Informed Consent Form because this is an observational study, without identification of patients or professionals. In order to carry out the observation, prior approval was obtained from the head of the sector and later, the team was clarified about the research objectives, as well as about all the commitments regarding the confidentiality of the information.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

During the study period, 47 PICC insertion procedures were observed in 33 NBs, with an average of 1.4 PICC per NB. There was a sample loss of seven procedures due to the impossibility of observation, and two were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria.

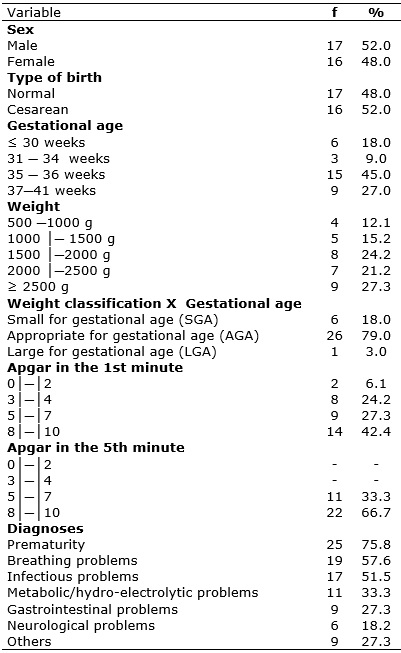

The profile of newborns who received PICC reveals a male trend, 17 (52.0%), according to Table 1.

TABLE 1:

Characterization of the newborns submitted to the insertion procedure of

PICC. UTIN-HUM, Maringá-PR, Brazil, 2015. (N=33)

Similar studies2,3,19,20 have ratified the higher incidence of prematurity in newborns of this sex, who are more vulnerable to pre- and perinatal alterations, have a worse prognosis after preterm birth, and are also more susceptible to congenital malformations and mortality 21,22.

Regarding gestational age, 24 (72.7%) were preterm, of whom a large part had bordering gestational age (35-36 weeks) - 15 (45%). The majority - 24 (72.7%) of the newborns were born weighing less than 2500 grams, from cesarean birth, 16 (52%), and had a diagnosis of prematurity, 25 (75.8%). See Table 1.

Prematurity is one of the main causes of hospitalization in NICU3, being frequent the cesarean birth2,19 due to maternal and fetal complications that require intervention in the gestation before its end23. Low birth weight has a strong association with the risk of dying in the first year of life, development problems during childhood and the occurrence of morbidities in adulthood24.

The Apgar score in the first minute was equal to or less than seven in 19 (57.6%) NBs, indicating that most of them had mild to severe asphyxia, however, at the fifth minute, only 11 (33.3%) maintained this score (Table 1). The Apgar score in the fifth minute became the most important reference for the diagnosis and prognosis of asphyxia, whereas the team does not wait the first minute score to begin resuscitation maneuvers. On the other hand, the score in the first minute seems to have relevance in the prognosis of mortality25.

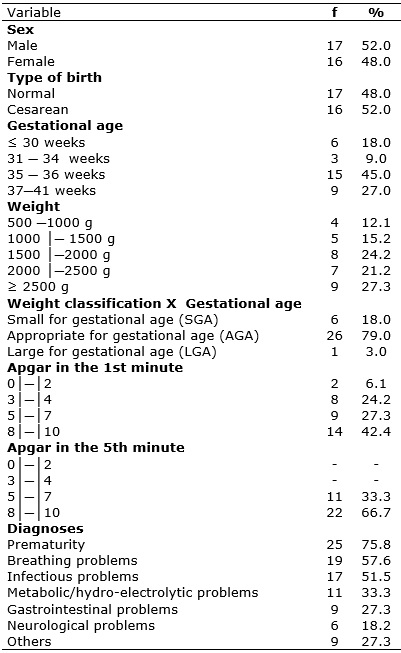

Parenteral nutrition (PN), in 27 (57.4%) NBs, was the preponderant indication for PICC insertion, according to Table 2, which is in line with the recommendations described in the literature1,26.

TABLE 2:

Distribution of PICC procedures according to indication, number of

procedures, chronological age and other variables. UTIN-HUM. Maringá-PR,

Brazil, 2015. (N=47)

PN is necessary to provide adequate nutritional support for growth and development, especially for preterm NBs, who do not have gastric capacity for full nutrition27. Because it is a solution with high glucose concentrations, it is recommended that it is not infused by peripheral venous access1,26.

There was more than one PICC insertion procedure in 15 (32%) of the infants investigated, according to Table 2. The need for more than one PICC procedure during hospitalization of the newborn was also identified in others similar studies, with variability of 11%2 to 15.6% 20. Such need may be justified by the prolonged length of stay in NICUs, especially of premature infants, as well as by problems with the maintenance of PICC.

It should be noted that analgesic and/or sedative measures for pain relief were used in less than half - 22 (46.8%) of the newborns submitted to PICC insertion. A study with the objective of characterizing sedation and analgesia measures in newborns submitted to this procedure found that only 34.6% of the insertions occurred with analgesia and sedation20. A study performed at a university hospital in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, with 36 NBs revealed a higher percentage, in which 80% of PICC were inserted with previous analgesia19.

On the other hand, sweetened solutions/LM were used in the majority - 26 (55.3%) - of the NBs, and it was not used only in mechanical ventilation cases - 17 (36.2%). It is noteworthy that 44 (93.6%) of the newborns received at least one measure to control pain, being this pharmacological or not, evidencing that there is a concern of the team with the pain of the NBs. See Table 2.

The use of non-pharmacological strategies has proven to be effective for the management of pain in NBs20,28, however, with restrictions imposed by the clinical conditions and devices installed in these patients 20. In this study, the measures used were non-nutritive suction, facilitated containment and sweetened solutions, but they did not include all NBs.

A survey conducted in Italy aimed at documenting current hospital practices for analgesia in NICU. After 5 years of the publication of the national guidelines, it was verified that non-pharmacological measures for pain control during the PICC installation were used by 56.5% of Italian NICUs28.

Non-nutritive suction and oral sweetened solutions promote a calming effect, contributing to the reduction of pain in NBs. There should be an association of both measures, when possible, because the calming effect of suction is potentiated when glucose is used29,30.

The facilitated containment was used in 10 (21.3%) infants submitted to the PICC insertion. The use of facilitated containment to perform the PICC procedure promotes comfort, keeps the NB warm and favors vasodilation 29, but it is hindered in cases where there is a need to let the NB limbs, especially the lower ones, exposed for PICC insertion. Thus, non-pharmacological measures are accessible, safe and inexpensive 28,30, and should be used for pain management whenever the NB's conditions allow.

Regarding the age of the newborn at insertion, the majority of the attempts occurred in the early neonatal period - 34 (72.3%), and the attempts to install the device before the RN completes one day of life stands out - 11 (23.4%), according to Table 2. Research performed in a school hospital in southern Brazil found that 61% of PICC were inserted in the first day of life of the NB3. These results suggest that, in Brazil, professionals have chosen the PICC as the first choice among central accesses1. In turn, international surveys have shown that PICCs are inserted later, on average, between 5.86 and 11 days of life of the newborn31, with indications of use of umbilical venous catheter with subsequent replacement by PICC32.

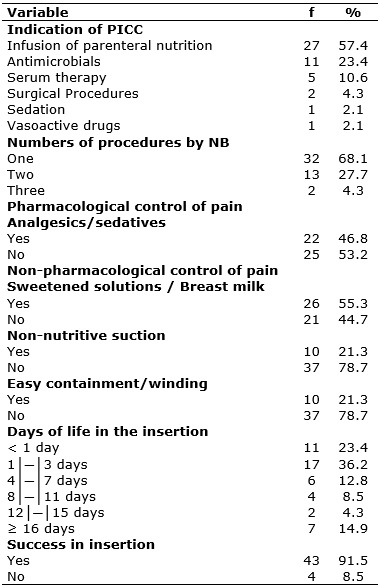

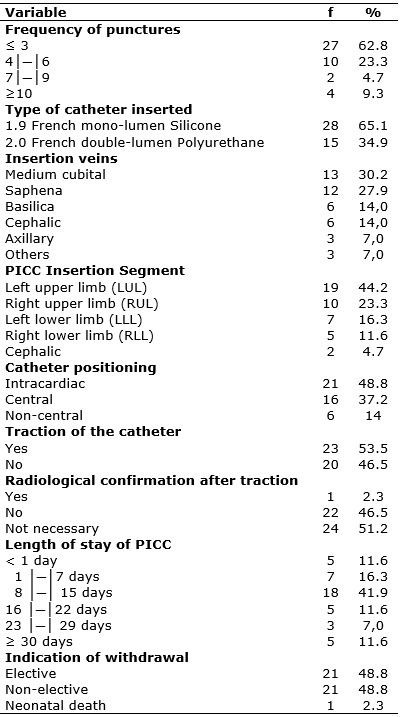

There was a high success rate of insertion, with 43 (91.5%) of the PICCs installed, and most of these devices were inserted up to the third attempt of puncture, 27 (62.8%), according to Table 3. This percentage is lower than that of a study performed in a private hospital in São Paulo, in which 71.1% of PICCs were inserted with three attempts or less8. The insertion of the PICC in the first days of life of the NB facilitates the passage of the catheter and reduces the need for repeated peripheral venous punctures3.

TABLE 3:

Distribution of successful procedures by puncture frequency and other

variables. UTIN-HUM, Maringá-PR, Brazil, 2015. (N=43)

The predominance of single-lumen silicone catheters, 28 (65.1%), was verified, as shown in Table 3. The preference for 1.9-french diameter single-lumen silicone catheters was noted in this study and in others studies on the subject2,7. The small diameter of this catheter is compatible with the venous network of premature infants, and its material is more malleable, which favors its insertion when compared to the PICC made of polyurethane10.

The double-lumen PICC was installed in 15 (34.9%) NBs and is indicated for multi-therapies, especially when there is need for parenteral nutrition, which should preferably be administered in exclusive route. However, its use should be well delineated, as the more lumens, the greater the risk of infection of the catheter34. A study found that the use of polyurethane catheter was related to the removal of the device due to suspicion of infection7.

Regarding the insertion veins, the ulnar was chosen in 13 (30.2%) cases, followed by the saphenous vein (27.9%). These were the most used, according to Table 3, which differs from data from another study, in which the axillary and basilic veins were the most used as insertion site33. Even with a high number of valves and the need for progression of a long extension of the catheter, the use of the saphenous vein has been used as a venous site for the PICC3,33. Such option may be associated to the fact that the lower limbs are not commonly used for peripheral venipuncture and collection for laboratory tests, preserving the venous network.

Another aspect worthy of note was the use of the axillary vein 3 (7%) as the last choice of access, constituting one of the least used options for PICC puncture. This fact can be justified by the proximity of this access to the axillary artery and the risk of arterial puncture34. Nevertheless, a randomized clinical trial with 62 NBs concluded that the insertion of PICC into the axillary vein is related to fewer complications when compared to other insertion sites. This result is supported by the fact that the distance between the axillary vein and the end point of the distal end of the catheter is smaller33.

The left body hemisphere - 26 (60.5%) - was the most punctured, being the left upper limb the most accessed - 19 (44.2%), according to Table 3, since it is a routine in the investigated unit to preserve this limb for PICC. These results diverge from the findings of another study that pointed to the right hemisphere and the right upper limb as the favortite ones for access34, a fact that may be related19,33,34, fundamentally, to the proximity of this hemisphere with the vena cava 19,33,34. Regarding the initial location of the distal end of the device, 16 (37.2%) had the central location as the initial and 21 (48.8%) had intracardiac positioning, according to Table 3, and of these, only one was not pulled. This result is superior to that found in a retrospective study with 163 newborns who used PICC, in which only 25% of the devices were adequately located2; and is lower than that found in a study in which 74.2% PICCs were located in the superior vena cava19. It should be noted that only one catheter was confirmed by radiography after the traction.

The correct location of the catheter tip is paramount in the prevention of complications inherent to PICC26. The optimal location of the catheter tip, when inserted by access in the upper limbs, is the SVC or cavoatrial junction31, and when inserted by lower limbs, it is the IVC26. Pulling the catheter is necessary whenever the PICC is positioned inside the heart. In this study, almost all the intracardiac catheters were pulled, however, their location was not confirmed by radiography after the traction, since this is not established by the unit, due to the exposure of the NB to radiation.

Research aimed to evaluate and describe the practices involved in the insertion and maintenance of PICC in a level III NICU in the United States, to compare the results with published guidelines revealed that 21.5% of the NICUs do not adhere to the practice of radiological confirmation of the location of the tip of the PICC after traction26. However, there are recommendations that the distal end of the device be confirmed by radiological examination before fluid infusion is initiated26,31. In addition, the PICC traction may result in placement of the tip below the optimal position31.

In this sense, studies have suggested that, regardless of the punctured vein, the radiographs for the location of the PICC should be performed with the arm in adduction with elbow flexion. This position leaves the catheter in the deepest central location, avoiding excessive traction, in addition to favoring self-regulation by the preterm NB by bringing the hand closer to the mouth31.

Catheters whose tips left out of the vena cava have been associated with an increased risk of complications such as thrombosis, phlebitis, pleural effusion, occlusion, cardiac tamponade26,31 and a complication rate eight times higher than when they are positioned in SVC or IVC26.

The length of stay of the PICC ranged from less than 24 hours to 45 days. The average use or stay of the PICC in this study reached 13 days, a result superior to that found in a national study in which the average was 11.73 and the international average, of 10.2 days32.

The withdrawn of the device was justified equally between elective - 21 (48.8%) and non-elective reason - 21 (48.8%), according to Table 3. National studies have shown high percentage of unscheduled withdrawal of the device, with values that reach 62.2%19, thus reflecting that problems with PICC conservation have been recurrent in many NICUs in the country.

CONCLUSION

This study was pioneer in the NICU of a university hospital in the south of Brazil, with the purpose of evaluating the insertion, maintenance and withdrawal of PICC. The PICC was found to be appropriately indicated and, in line with the findings of other similar studies, has been inserted earlier and earlier, as an alternative of a central venous access for the at-risk neonates and as a reflection of the increasing dominance of this technique by the nurses.

On the other hand, there are problems for the insertion and maintenance of this device, evidencing the lack of established routines for pain management, besides difficulties related to the central positioning and early withdrawal of the device, which sometimes occurs before the end of the treatment. In view of the findings described in this study, there is the need to enhance the knowledge of the nursing team regarding the management and use of the PICC. This bias must be filled by continuing education activities with the nursing team for the increasing qualification in the use of this and other health devices. In addition, further research should also be encouraged for the development of new technologies that support the insertion of the PICC with fewer attempts and with the guarantee of central positioning.

REFERENCES

1.Reis AT, Santos SB, Barreto JM, Silva, GRG. The use of the percutaneous catheter in neonates of a state public hospital: a retrospective study. Rev. enferm. UERJ [Internet].2011 [cited in Sep 21 2016];19(4):592-7. Available from: http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v19n4/v19n4a15.pdf

2.Cabral PFA, Rocha PK, Barbosa SFF, Sasso GTMD, Pires ROM. Analysis of the use of the peripherally inserted central catheter in a neonatal intensive care unit. Rev. eletrônica enferm. [Internet].2013 [cited in 2016 Oct 10]; 15(1):96-102. Available from: https://www.fen.ufg.br/fen_revista/v15/n1/pdf/v15n1a11.pdf

3.Jantsch LB, Neves ET, Arrué AM, Kegler JJ, Oliveira CR. Use of the peripherally inserted central catheter in neonatology. Rev. baiana enferm. [Internet].2014 [cited in 2016 Oct 15]; 28(3):244-51: Available from: http://www.portalseer.ufba.br/index.php/enfermagem/article/view/10109/8985

4. Wojnar DG , Beaman ML . Peripherally inserted central catheter: compliance with evidence-based indications for insertion in an inpatient setting. J Infus Nurs.2013;36(4):291-6.

5.Costa LC, Paes GO. Applicability of nursing diagnoses as subsidies for indication of peripherally inserted central catheter. Esc. Anna Nery Rev. Enferm. [Internet]. 2012 [cited in 2016 Oct 29]; 16(4): 649-56. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-81452012000400002

6.Singh A, Bajpai M, Panda SS, Jana M. Complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheters in neonates: Lesson learned over 2 years in a tertiary care centre in India. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg.2014;11(3):242-7.

7.Duarte ED, Pimenta AM, Silva BCN, Paula CM. Factors associated with infection from the use of peripherally inserted central catheters in a neonatal intensive care unit. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. [Internet].2013 [cited in 2016 Sep 10]; 47(3): 547-54. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0080-62342013000300547

8.Dórea E, Castro TE, Costa P, Kimura AF, Santos FMG. Management practices of peripherally inserted central catheter in a neonatal unit. Rev. bras. enferm. (Online). 2011 [cited in 2017 Feb 14]; 64(6): 997-02. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-71672011000600002&lng=en

9.Montes SF, Teixeira JBA, Barbosa MH, Barichello E. Occurrence of complications related to the use of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in newborns. Enferm. glob. [internet]. 2011 [cited in 2016 Nov 10]; (24): 10-18. Available from: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/eg/v10n24/pt_clinica1.pdf

10.Lienemann M, Takahashi LS, Santos RP. Vascular access in neonatology: peripherally inserted central catheter and peripheral venous catheter. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Med. Sorocaba. [Internet]. 2014 [cited in 2017 Ago 04]; 16(1): 1-3. Available from: http://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/RFCMS/article/view/17473

11.Belo MPM, Silva RAMC, Nogueira ILM, Mizoguti DP, Ventura CMU. Knowledge of neonatology nurses about peripherally inserted central venous catheter. Rev. bras. enferm. (Online).2012 [cited in 2017 Ago 03]; 65(1): 42-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reben/v65n1/06.pdf

12.Park JY, Kim HL. A comprehensive review clinical nurse specialist-led peripherally inserted central placement in Korea: 4101 cases in a tertiary hospital. J. infus. nurs. 2015; 38(2):122-8.

13.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am. j. infect. control.2011; 39 (4 Suppl 1): S1-34.

14.Vieira AO, Campos FMC, Almeida DR, Romão DF, Aguilar VD, Garcia EC. Nursing care of neonates with peripherally inserted central catheter. Rev. eletronica gest. saúde. 2013; 4(2): 188-99.

15. National Health Surveillance Agency. Bloodstream infection. Guidelines for prevention of primary bloodstream infection.2010 [cited in 2017 Mar 04]; 1: 1-53. Available from: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/ef02c3004a04c83ca0fda9aa19e2217c/manual+Final+preven%C3%A7%C3%A3o+de+infec%C3%A7%C3%A3o+da+corrente.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

16.Johann DA, Lazzari LSM, Pedrolo E, Mingorance P, Almeida TQR, Danski MTR. Care of peripherally inserted central catheter in the neonate: an integrative literature review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2012:46 (6):1503-11.

17. National Health Surveillance Agency. Diagnostic criteria of infections related to health care neonatology. 2013 [cited in 2016 Sep 22]. 1-70. Available from: http://www20.anvisa.gov.br/segurancadopaciente/images/documentos/livros/Livro3-Neonatologia.pdf

18.Paiva ED, Kimura AF, Costa P, Magalhães TEC, Toma E, Alves AMA. Complications related to the type of percutaneous catheter in a cohort of neonates. Online braz. j. nurs. (Online). 2013 [cited In 2016 Apr 12]: 12(4): 942-52. Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/4071

19.Mingorance P, Johann DA, Lazzari LSM, Pedrolo E, Oliveira GLR, Danski MTR. Complications of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) in neonates. Ciênc. cuid. saúde. [Internet]. 2014 [cited in Sep 22 2016]; 13(3): 433-38. Available from: http://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/CiencCuidSaude/article/viewFile/18476/pdf_325

20.Costa P, Bueno M, Oliva CL, Castro TE, Camargo PP, Kimura AF. Analgesia and sedation during placement of peripherally inserted central catheters in neonates. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. [Internet]. 2013 [cited in 2016 Jul 30]; 47(4): 801-7. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0080-62342013000400801&lng=en&tlng=en

21.Almeida CGM, Rodrigues OMPR, Salgado M.H. Differences in the development of at-risk boys and girls. Bol. psicol. (Online).2012 [cited in 2016 Ago 01]; 62(136): 1-14, 2012. Available from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0006-59432012000100002&lng=pt&tlng=pt

22. Skiöld B, Alexandrou G, Padilla N, Blennow M, Vollmer B, Adén U. Sex Differences in outcome and associations with neonatal brain morphology in extremely preterm children. J. pediatr [Internet].2014 [cited 2016 Sep 10]; 164(5):1012-8. Available from: http://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476%2813%2901597-7/fulltext

23.Ribeiro ED, Fontoura IG, Cordeiro JR, Silva PC, Chaves RG. Regional Maternal Infant Hospital of Imperatriz, Maranhão: preterm delivery route in October and November 2013. J. manage. prim. health care.2014 [cited in Sep 09 2016]; 5(2): 195-201. Available from: http://www.jmphc.com.br/saude-publica/index.php/jmphc/article/view/216

24.Viana KJ, Taddei JAA, Cocetti M, Warkentin S. Birth weight of Brazilian children under two years of age.Cad. Saúde Pública (Online). 2013 [cited in Sep 15 2016]; 29(2):349-56. Available from: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/csp/v29n2/21.pdf

25.Oliveira TG, Freire PV, Moreira FT, de Moraes J da S, Arrelaro RC, Ricardi SR, Juliano Y, Novo NF, Bertagnon JR. Apgar score and neonatal mortality in a hospital located in the southern area of São Paulo City, Brazil. Einstein (Sao Paulo. Online). 2012 [cited in Oct 10 2015]; 10(1): 22-8. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1679-45082012000100006&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en

26.Sharpe E, Pettit J, Ellsbury D.L. A national survey of neonatal peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) practices. Adv. Neonatal Care. 2013; 13(1): 55-74.

27. Moyses HE, Johnson MJ, Leaf AA, Cornelius VR. Early parenteral nutrition and growth outcomes in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. j. clin. nutr. [Internet]. 2013 [cited in 2016 Sep 17]; 97:816–26. Available from: http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/97/4/816.long

28. Lago P, Garetti E, Boccuzzo G, Merazzi D, Pirelli A, Pieragostini L, Piga S, Cuttini M, Ancora G .Procedural pain in neonates: the state of the art in the implementation of national guidelines in Italy. Pediatric anesthesia. 2013; 23 (5): 407–14.

29.Mickler P. Neonatal and Pediatric Perspectives in PICC Placement. JJ. infus. nurs. 2008; 31(5): 282-5.

30.Stevens B. Yamada J, Lee GY, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane database syst. rev. (online). 2013 [cited in Oct 12 2016]: 1;1-137. Available from: http://www.manuelosses.cl/BNN/Sacarosa_dolor%20_RNs_cuan%20segura.%20FULL.pdf

31. Newberry DM, Young TE, Robertson T, Levy J, Brandon D. Evaluation of neonatal peripherally inserted central catheter tip movement in a consistent upper extremity position. Adv. Neonatal Care. 2014; 14(1): 61-68.

32. Arnts IJ, Bullens LM, Groenewoud JM, Liem KD. Comparison of complication rates between umbilical and peripherally inserted central venous catheters in newborns. J. obstet. gynecol. neonatal nurs. 2014; 43(2): 205-15.

33. Panagiotounakou P, Antonogeorgos G, Gounari E, Papadakis S, Labadaridis J, Gounaris AK. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters: frequency of complications in premature newborn depends on the insertion site. J. perinatol. 2014; 34: 461-3.

34.Costa P, Vizzoto MPS, Olivia CL, Kimura AF. Sítio de inserção e posicionamento da ponta do cateter epicutâneo em neonatos. Ref. enferm. UERJ. [Internet]. 2013 [cited in 2016 Oct 15]; 21(4): 452-7. Available from: http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v21n4/v21n4a06.pdf