*Sex: M: Male; F: Female

FIGURE 1: Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics. Rio de Janeiro, 2014.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Adolescents facing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: contributions to oncology nursing

Luana Sena PimentaI; Benedita Maria Rego Deusdará RodriguesII; Sandra Teixeira de Araújo PachecoIII; Michelle Darezzo Rodrigues NunesIV; Ann Mary Machado Tinoco Feitosa RosasV; Ana Claudia Moreira MonteiroVI

I

Nurse. Master. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Email:

luanasena.pimenta@gmail.com

II

Nurse. Doctor. Full Professor. Nursing School, Rio de Janeiro State

University, Brazil. Email: benedeusdara@gmail.com

III

Nurse. Doctor. Assistant Professor. Nursing School, Rio de Janeiro State

University, Brazil. Email: stapacheco@yahoo.com.br

IV

Nurse. Doctor. Assistant Professor. Nursing School, Rio de Janeiro State

University, Brazil. Email. Email: mid13@hotmail.com

V

Nurse. Doctor. Assistant Professor. Anna Nery Nursing School, Federal

University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Email: annmaryrosas@gmail.com

VI

Nurse. Master in nursing. Studying for a Doctor's Degree from Rio de

Janeiro State University. Professor at Universidade Estácio de Sá, Brazil.

Email: ana-burguesa@hotmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2017.26940

ABSTRACT

Objectives: to describe adolescents' expectations before submitting to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and to analyze comprehensively what they expect from life after transplantation. Methods: the sociological phenomenology of Alfred Schutz provided the theoretical and methodological framework. The participants were eight adolescents from 12 to 18 years old at a bone marrow transplantation service of a Brazilian federal referral hospital. Phenomenological interviews were conducted in 2014 after consulting the research ethics committees of the proponent (#686.508) and co-participant (#63/14) institutions. Results: five categories emerged from the analysis: leaving difficulties behind; being cured; having a normal life; having a profession; and forming a family. The adolescents' life expectations after transplantation point to being cured and their outlook is focused on the possibility of a normal life. Conclusion: the study findings recommend multidisciplinary professional work, in which the adolescents, families and health team work together as active participants in this process.

Keywords: Adolescent; transplantation; oncology; pediatric nursing.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer has become a public health problem for the developed world and developing nations. In Brazil, the estimates for 2014 are pointing to approximately 576 thousand new cases of cancer, thus stressing the amplitude of this issue in the country1. It has been further estimated that there will be around 11,840 new cases of cancer in children and adolescents up to the age of 191. Deaths from cancer, in the overall set of causes of death during childhood, have become the main mortality causes in this age group. In addition, an unequal access to diagnoses and treatment with specialized services is also a contributing factor making cancer in children and adolescents a major public health problem today2.

The advances in the treatment against childhood and adolescent cancer have been extremely significant. Currently, about 70% of all children and adolescents suffering from cancer can be cured, if diagnosed early and treated at specialized centers, and most of them will enjoy good life quality after a proper treatment3.

Each patient treads a common path where their struggle against the disease is intense and their desire for cure becomes the strength required to overcome every situation faced. This makes them go through several treatment lines, including Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT). HSCT can be defined as a procedure aiming to replace sick bone marrow with a healthy one. This therapy has been enhanced over the years and, when compared to other fields of medicine, can be considered to be relatively new4.

In view of the impact of cancer on teenage and the progressively growing number of cases of HSCT in this period of life, this study has been prepared considering the contributions to the role of nurses toward adolescents undergoing HSCT, due to particularities relating to the procedure and the experiences regarding it.

Thus, the following guiding questions have been raised: what are the adolescents' expectations regarding HSCT? And what do these adolescents think about their return to everyday life after going under the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation?

In this regard, the purpose of this study is to place an emphasis on the adolescent's life expectations relative to the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and, for that purpose, the following goals have been set: to describe the adolescents' expectations before they undergo HSCT; and to comprehensively analyze the adolescent's life expectations in the post-HSCT phase.

THEORETICAL-METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

Phenomenology is a philosophical movement founded by Hurssel (1859- 1938), in Germany, which according to him is a movement of our sight away from experienced realities to the feature of being experienced5.

This philosophical method reveals the daily world of the being where an experience occurs (lived world) and leads to a description of their experiences, thus seeking to explore phenomena, as they appear to consciousness, of that which is given6.

Alfred Schutz' sociological phenomenology is adequate for this study because it seeks a meaning to action, from the adolescents' consciousness, focusing on the adolescents' life expectations in connection with the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

For Schutz, an action is human conduct consciously projected by the person, that is, an action is conduct devised in advance, based on a preconceived project. Action originates in the person's consciousness7.

These actions are of a motivated nature and thus can indicate goals for the future defined as "in-order-to motives", and "because motives" refer to actions based on past experiences8.

The search for "in-order-to motives" will reveal what these adolescents expected as a change in their lives, how they feel about the procedure, their fears and achievements, and their motivation toward HSCT. Once these particularities are known, the nurse will be allowed to get along with this patient in a more proper manner to their needs, and will be able to plan some assistance to address more than biological needs.

For Schutz, the world of everyday life is not a private world, but an intersubjective one instead, filled with social relations, shared, experienced, and interpreted by other similar persons, who, by acting and being affected by each other, produce a mutual relationship8.

Thus, a type-based classification turns unique individual actions, by unique human beings, into typical functions, with typical social roles, and is key so that interactions can take place in everyday life9. Therefore, understanding a phenomenon, based on the descriptions of the adolescent's expectations in the post-HSCT phase, allows for an interpretative analysis that has enabled us to understand their experiences.

Methodological course

This is a qualitative study, grounded in Alfred Schutz' sociological phenomenology. The scenario was a bone marrow transplantation unit, located at a nationally recognized federal hospital, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The study participants were eight adolescents, in the 12-18 years old age group, as defined by the Brazilian Youth and Adolescent Statute (ECA) 10, all of whom already in the post-HSCT phase and on partial hospitalization or already discharged at the time.

In order to conduct this study, the project was submitted to and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the proposing and co-participating institution (opinion No. 686.508) (REC registration No. 63/14), covering the ethical aspects of the research involving human beings. In compliance with the provisions of Resolution No. 466/12 11, approved by the National Council of Health of the Ministry of Health, adolescents from 12 to 17 years old signed the acceptance form and their legally responsible family members signed the informed consent form for participation in the research.

The adolescents' right to decide whether or not to participate in the research was assured, as well as their right to withdraw at any time, at no cost and without any constraint. The participants' identities have been kept confidential, and aliases have been used. Data collection took place between August to September 2014, as already approved then by the REC's of the institutions engaged in the research.

A phenomenological interview was used as a tool to capture the speeches, allowing the subject experiencing the phenomenon to express the meaning of their action taken in the world of their relations. This concerns the client's space and their time, aiming to capture their subjectivity, their way of experiencing the world through their manner of signifying it, expressing their behavior and their way of acting when facing certain situations12.

To capture data from the adolescents, an interview was scheduled in advance through a telephone call for the date of their appointment at the post-HSCT in-patient care department or at their own houses, and three of them chose to give the interviews at home, while the other five thought it was better if the meetings could take place at the institution, on the day of their follow-up appointment at the in-patient care department.

The interviews were recorded at a reserved place, with the researcher and the adolescent and, sometimes, with some family member present. It is worth reminding that the interviewee's independence and the confidentiality of the information provided were maintained.

The interviews were guided by the following guiding questions:

· Tell me how this period of illness went for you.

· What are your expectations regarding the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation?

· What do you expect for your daily/routine life now after undergoing the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation?

The speeches were later transcribed and analyzed so that they could then be categorized according to the phenomenological approach. Categorization was effected by carefully reading and critically analyzing the contents of the speeches, making it possible to identify and describe the meanings of the action and thus understand the investigated phenomenon. The speeches in the text have been identified with letter A as in adolescent, followed by a number corresponding to the order of interviews and the post-HSCT time. For instance, A1 – 9 months means first adolescent to be interviewed, who at that moment had had HSCT 9 months before.

The categories resulting from studies grounded in Alfred Schütz' social phenomenology are called concrete and constitute objective summaries of the various meanings of action emerging from the subjects' experiences 13.

Upon the comprehensive analysis, the interviewees' speeches were read many times in order to look for any existing interrelations, that is, what these speeches had in common, aiming to capture the in-order-to reason. Thus, a convergence of the in-order-to reason allowed comprehending the meaning of action into categories that will be presented below.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

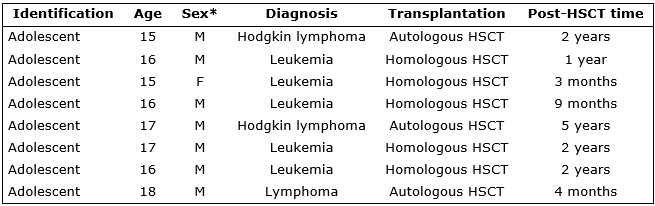

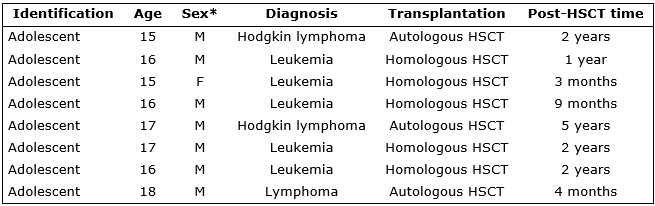

The study was joined by eight adolescents in a post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation phase, at ages ranging from 12 to 18, mostly males. The post-transplantation time varied from three months to five years. All participants were residents of the state of Rio de Janeiro, some of them from different cities. See Figure 1.

*Sex: M: Male; F: Female

FIGURE 1:

Participants' demographic and clinical characteristics. Rio de Janeiro,

2014.

By carefully reading the speeches of the adolescents-subjects in the study, it was possible to capture five concrete categories of the experience reflecting their expectation when they undergo HSCT. Then the categories and the corresponding speeches are described.

Leaving difficulties behind

The adolescents' first replies would always refer to the impact of diagnosis and the challenges faced throughout the path from discovery to transplantation. From the memories of all the limitations posed by the disease, which are now in the past, to the death of acquaintances during treatment.

I got really discouraged, it got me thinking about many things... what could this be, why did it happen to me (A4 - 9 months)

I used to have a lot of fun, I went to school, but I had to stop it all because of the disease. Then I was hospitalized for 2 months, the worst months. (A3 - 3 months)

I was hospitalized for 30 days and could not even see the sunlight, or know how the weather out there was. (...) That's when I went a bit crazy, I was sort of depressed, I would cry often, couldn't sleep . (A5 - 1 year)

...it's been almost two years since I got in a swimming pool for the last time. (A1 - 1 year)

...I feel bad because I lost a friend, but he still had residues of the disease in his blood. My mother suffered a lot with his passing (...) and so did I. (A2- 1 year)

Although the emphasis of the interview was not the discovery of the disease and the challenges that it brought, these feelings are so strong and present in the adolescents' lives that they could not help but mention them during the conversation, though now as something experienced in the past.

Being cured

When the adolescents were asked about their expectations regarding HSCT, their search for a cure and return to activities performed before the disease were the highlights.

It's the cure, so I can return to a normal life once and for all. (A2 - 1 year)

Well, I expected to get a cure, being cured. And having my life back [...] (A3- 3 months)

I immediately held onto my faith in God and was sure that I would leave there cured. (A5 - 5 years)

Being cured, getting well, getting better. (A7 - 2 years)

...when I was hospitalized, my expectations were to not get back, but it changed a bit... now I'm going through a radiation therapy, but my expectation is to leave already cured. (A8 - 3 months)

In this manner, the concept of action described by Schutz allows us to understand how intentionality emerges from these adolescents in search of a cure. Just like the diagnosis of cancer carries a sign of death, a transplantation leads them to a hope for life. Thus, adolescents suffering from cancer hold onto an inner faith regarding their cure, anxiously waiting for the moment when they will be free from the disease14.

In terms of the cure for the disease, some adolescents refer to it as a possibility of experiencing what was taken way from them, in their eyes, as soon as they started the cancer treatment.

It is worth stressing that their speeches produced a meaning for cure that goes beyond an absence of disease or a disease-free survival. For these adolescents, cure is related to a return to the activities performed in their daily lives, without needing to come back to a hospital environment so often, as evidenced in the next category.

Having a normal life

The adolescents interviewed refer to the treatment that they experienced, in the period both before and after the transplantation, as a period when they had to abandon their routine and regular activities and were away from school, their social environment, and their relationship with friends.

The adolescents' speeches point to this point of view:

[...] keep living my life as usual. Without needing to go to the hospital every single day, as I once had to, like once a year, every 3 years. I've known people who visit the hospital every 3 years. That would be more of a normal life, right? (A1 - 1 year)

[...] I want to take care of animals. I want to have a dog and I want to be in a swimming pool again. I'm always telling people that I want to live on a farm, because I really want to have animals. I like to take care of them. I want to have a snake and an iguana too. (A1 - 1 years)

[...] studying, my friends [...] I really enjoyed studying, incredible as it may seem [...] I want to be able to attend a guitar course. And I want to go to the movies again. To be able to go to the São Januário stadium again. To watch games, which I often did. I want to go to the beach! (A3 - 3 months)

During the interviews, the adolescents stressed that they wanted to return to what they consider to be normal, and implied that a normal life is primarily related to their release from the obligation to go to the hospital, though it goes beyond that, as they mention things that they could do before the disease and that they were deprived of during the treatment period in order to maintain their health at minimum levels.

Both the adolescent and their family face a dual relationship with the hospital: to the same extent that it brings suffering, the hospital also represents a space for cure where they undergo the treatment and the tests seeking to have their lives saved and recover their health15. When hospitalization is interpreted by both the family and the child or adolescent as afflictive, this feeling may reflect in the future, depending on the time and frequency of hospitalization, the disease severity, the medical procedures, the adaptation ability, the level of physical, cognitive, and emotional development, and the family relationship 15. From this perspective, the in-order-to reason of these adolescents when undergoing HSCT is saving their lives and recovering their health16.

Having an occupation

When asked about what they expect from their lives after the transplantation, the adolescents revealed plans for the future that never ceased to be drawn during the treatment period, including dreams about professional satisfaction.

Well, [...] I want to graduate, I want to attend 2 college courses: veterinary and biology [...] I want to take care of animals. (A1 - 2 years)

A cook. What I plan on doing the most is cooking, I'm going to enhance this ability and further down the road I can have my own restaurant, which I've always wanted.(A2 - 1 year)

...I'm planning to do business administration, or even get in the field of civil engineering. (A5 - 5 years)

I want to attend a preparatory course for ESA- Military school. (A8 - 3 months)

The end of the treatment, represented by the transplantation, makes their future professional plans more feasible and possible.

In addition to cure, it has been noticed that the adolescents would never take the disease as part of themselves, but rather only as something temporary, and they express their wish for a normal life like before, making plans for the future in all aspects14.

In spite of the adolescents' wishes regarding their professional future, a study has revealed that its subjects reported a number of physical and emotional aspects resulting from the cancer treatment that could potentially compromise their ability to work17. The economic and work-related experiences mentioned by the subjects during and after treatment and transplantation include job insecurity, discrimination, lack of professional direction, delayed goals, financial losses, mobility restrictions at work, and physical and mental limitations17.

Another study has added that the sequelae from the treatment have physical and social repercussions on their lives, and when they recover or resume their lives following a childhood-adolescent cancer, they need to make adaptations to their routine, such as when performing labor and leisure activities, which, in cultural terms, account for their independence, entertainment, and socialization18.

Schutz tells us that a man of natural attitude is "biographically located in the lifeworld" and has knowledge of his world. The lifeworld is full of experiences, which will drive the individual toward the action16 . However, one can only apprehend this attitude through listening and attention. That is, upon an effort to listen to these adolescents, it is possible to get to know the reasons driving them to their future life, their planning, and activities that are unique to them.

Starting a family

The adolescents interviewed expressed feelings about their lived experience going beyond aspects relating to the limitations posed by the treatment and were open to reveal their personal desires, such as starting a family.

Then I want to have a boy and a girl. But, for a twin couple like this, I would need to have an artificial insemination. So I'll have to have an insemination. (A1 - 2 years)

Sure, I want to have my own family, my own house [...]. (A5 - 5 years)

Despite their expectation about starting a family and having children, the physical consequences from the cancer treatment can include infertility 19-20. As a confirmation of that, most of the subjects in a study have revealed that they were not informed about the risk of infertility at any time during treatment, which may be the case with the study participants as well21.

Thus, a comprehensive analysis of the adolescent's life expectations in the post-HSCT phase leads to the establishment of a type characterized as follows: the adolescents are hoping to have their lives back, the way it was before the diagnosis of the disease, staying cured/healthy to move on with their lives and having an occupation and a family. They want to stop being different, having different habits and limitations, in order to have a common, regular life, with a routine that is similar to that of most people.

CONCLUSION

The qualitative research with an emphasis on Alfred Schutz' sociological phenomenology has allowed for an understanding of the adolescent's life expectations regarding a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and their return to regular life routine after undergoing it. It has been noticed that the expectations of the transplant adolescents point to cure and their perspectives focus on the possibility of enjoying a normal life, after experiencing years of deprivation with the treatment, which have left deep marks. The transplantation experience for adolescents represents a new chance to live and change their way of seeing the world and life, even though there might be some time of isolation from family and their social relationships.

As we have noticed how much being deprived of contact with their beloved ones and the external environment impacts on these adolescents, this research suggests a search for feasible coping strategies to help adolescents during such a unique moment, such as establishing support groups made up of adolescents, with periodical meetings, experience exchange, conversation, and interaction, aiming to contribute to treatment evolution, since the way how an adolescent faces their lifeworld may directly influence their decisions and conduct throughout the treatment.

The study leads to a multidisciplinary professional action from the perspective of "us", that is, the adolescent-family-healthcare team, where everyone is part of it as an active component of this process.

This study contributes to reflections on precautions and actions aiming to improve the quality of the assistance dispensed to adolescents undergoing the transplantation. By getting to know these adolescents' life expectations, we can adapt the assistance so as to help them throughout this process, allowing them to acknowledge their new condition after the transplantation and then rebuild their daily life routine.

REFERENCES

1. Inca - Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva. Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Estimativa 2014: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2014.

2. Silva DS. Câncer da infância e da adolescência: tendência de mortalidade em menores de 20 anos no Brasil. [Master's thesis]. Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca; 2012.

3. Ministry of Health (BR). Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva [website]. Tipos de câncer: infantil 2013 [mentioned on May 01, 2015]. Available at: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/infantil

4. Ministry of Health (BR). Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Ações de enfermagem para o controle do câncer: uma proposta de integração ensino-serviço. 3rd. Ed. reviewed, updated, and extended. Rio de Janeiro; 2008a.

5. Capalbo C. Fenomenologia e ciências sociais. São Paulo: Idéias e Letras; 2008.

6. Silva JMO, Lopes RLM, Diniz NMF. Fenomenologia. Rev Bras enferm. 2008; 61(2):254-7.

7. Schütz A. Collected papers I: the problem of social reality. Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1962.

8. Wagner H. Sobre fenomenologia e relações sociais: Alfred Schutz. Petrópolis(RJ): Vozes; 2012.

9. Nunes MGS, Rodrigues BMRD. Tratamento paliativo: perspectiva da família. UERJ nursing magazine. 2012; 20(3):338-43.

10. Brazil. Children and Adolescents Statute (BR). Law No. 8069, dated July 13, 1990, Law No. 8242, dated October 12, 1991. 3rd ed. Brasília (DF): House of Representatives, Coordenação de Publicações; 2001.

11. Brazil. National Council of Health (BR). Resolution No. 466, dated December 12, 2012. To approve standards for regulating research involving human beings. [mentioned on May 11, 2015] Available at: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf

12. Jesus MCP, Capalbo C, Merighi MAB, Oliveira DM, Tocantins FR, Rodrigues BMRD, et al. A fenomenologia social de Alfred Schütz e sua contribuição para a enfermagem. USP nursing school magazine. 2013; 47(3): 736-41.

13. Schütz A. Fenomenologia del mundo social: introducción a la sociología compresiva. Buenos Aires(Ar): Paidós; 1972.

14. Ribeiro IB, Rodrigues BMRD. Cuidando de adolescentes com câncer: contribuições para o cuidar em enfermagem. UERJ nursing magazine. 2005; 13(3): 340-6.

15. Cicogna EC, Nascimento LC, Lima RAG. Children and adolescents with cancer: experiences with chemotherapy. Latino-Am Enfermagem magazine. 2010; 18(5): 864-72.

16. Schutz A. Bases da fenomenologia. In: Wagner H, (Organizador). Fenomenologia e relações sociais: textos escolhidos de Alfred Schutz. Rio de janeiro: Zahar; 1979.

17. Stepanikova I, Powroznik K, Cook KS, Tierney K, Laport GG. Exploring long-term cancer survivors' experiences in the career and financial domains: interviews with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2016;34(1-2):2-27.

18. Whitaker MCO, Nascimento LC, Bousso, RS, Lima RAG. A vida após o tratamento do câncer infanto-juvenil: experiências de sobreviventes. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2013; 66(6): 873-8.

19. Hammond C, Abrams JR, Syrjala, KL. Fertility and risk factors for elevated infertility concern in 10-year hematopoietic cell transplant survivors and case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:3511–7.

20. Jadoul P, Anckaert E, Dewandeleer A, Steffens M, Dolmans, MM, Vermylen C, et al. Clinical and biologic evaluation of ovarian function in women treated by bone marrow transplantation for various indications during childhood or adolescence. Fertil. Steril. 2011; 96: 126–33.e3.

21. Lahaye M, Aujoulat I , Vermylen C, Brichard B. Long-term effects of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation after pediatric cancer: a qualitative analysis of life experiences and adaptation strategies. Front Psychol. 2017; 8:704.