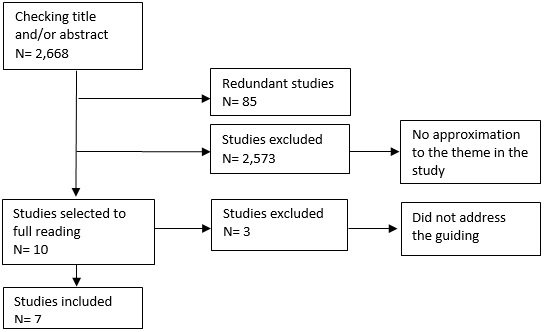

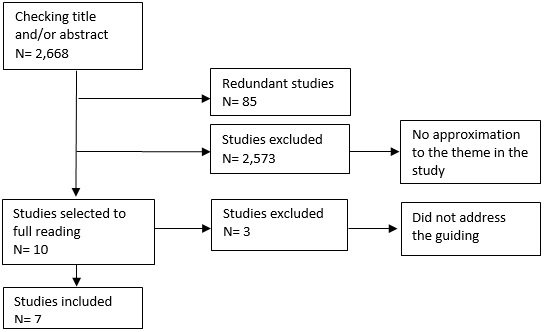

Figure 1: Selection process flow for reality-based review. Source: The writers (2016)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Educating to humanize: the transformer role of permanent education in the primary care humanization

Maria Tereza Soares Rezende LopesI; Célia Maria Gomes LabegaliniII; Vanessa Denardi Antoniassi BaldisseraIII

I

Nurse. Specialist. M.Sc. candidate in Nursing. Universidade Estadual de

Maringá, Paraná, Brazil. Nursing Department. E-mail: mterezalopes@hotmail.com

II

Nurse. M.Sc. Ph.D. candidate in Nursing. Universidade Estadual de Maringá,

Paraná, Brasil. Nursing Department. E-mail:

celia-labegalini-@hotmail.com

III

Nurse, Ph.D. in Sciences. Professor on the Graduate Course in Nursing at

Universidade. Estadual de Maringá, Paraná, Brasil. Nursing Department.

E-mail: vanessadenardi@hotmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2017.26278

ABSTRACT

Objective: to develop the theoretical principles of continuing education in health practices for deployment and use of the provisions of Brazil's National Humanization Policy in primary care. Method: realistic review of literature from 2003 to 2016, guided by the study question: what continuing health education practices have been used to deploy and organize National Humanization Policy provisions in the primary care context? Results: active learning methodologies and grouping were significant educational interventions used to deploy and use humanization provisions. On this evidence, two theories were identified to explain continuing education processes applied in primary care to deploy and use these provisions. Conclusion: continuing education practices are important to deploy and organize these provisions in primary care, and the theoretical principles developed can make primary health care workers receptive to their introduction, and facilitate this process.

Keywords: Continuing education; humanization of assistance; primary health care; public health policy.

INTRODUCTION

The National Policy for Permanent Education in Health (NPPEH) lies among the major articulators between education and practice. Implemented in 2004, it searched strategies in education and development of workers at the Single Health System (SHS) in face of the consolidation of the sanitary reform in Brazil1. The NPPEH aims at transforming work in the health area, stimulating critical, engaged, and technically efficient action, as well as the respect both to regional characteristics and the specific needs in the workers' education2.

Transformation and development in critical health education went on and in 2014 new guidelines were out for the implementation of NPPEH, among which the promotion of significant learning by means of active and critical methodologies. 3.

Simultaneously to the establishment of the NPPEH in 2003, the Health Department set forth the National Humanization Policy (NHP), aiming at strengthening the public health system by means of improving attention and management quality4. In face of both the ongoing social process of the SHS and the major role played by health professionals in it, the role of Permanent Health Education (PHE) must be enhanced as a relevant tool to ensure work force required for both humanized care5 and for integrating health practice.

The main scenario concerning transformations in Brazilian health has been translated as Primary Care (PC), regarded as the path to the universalization of actions country wide 6, in face of its major role on the Health Care Web.

METHODOLOGY

This is a reality-based review study, operating as a synthesis of qualitative research for the development of models and theories, as well as the establishment of intervention practices and policies in socially complex contexts. To conduct this study, we have gone through the six-step reality-based review7.

The first step comprised the definition of the review scope. The study question was formulated on the basis of the objectives set up, namely: What practices in PHE have been used for the implantation and organization of NHP devices in PC?

To that end, interventions concerning this study were spelled out on the basis of the reality-based review, granting that that term suggests interference over a process or over a phenomenon belonging in a certain context7.

The second step was related to the search for evidence. Literature search held the following inclusion criteria: full text articles published in Portuguese, English or Spanish from 2003 to 2016. Time limits were set up on the basis that the NHP was implanted in Brazil in 2003. Search was conducted on the basis of the combination of descriptors on nationwide and worldwide webs, by means of boolean operators "and" and " or".

On the first search combination of descriptors was as follows: ("health staff's attitude" or "health staff") and ("health education" or "permanent education") and ("assistance humanization" or "primary health care" or "public health policies" or "health family strategy" or "public health" or "single health system"), on the bases Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS), Base de Dados da Enfermagem (BDENF), Índice Bibliográfico Espanhol em Ciências da Saúde (IBECS) and Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO). Descriptors in English were used on the bases Publisher Medline (Pub Med), Web of Science and current Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), namely: ("Health Education" or "Education, Public Health Professional") and ("Primary Health Care" or "Public Health" or "Public Health Practice" or "Family Health" or "National Health Programs" or "Health Policy") and ("Health Personnel" or "Attitude of Health Personnel" or "Allied Health Personnel"). This search method gave out 2,046 publications.

However, no research result came out of this first search, which addressed this study question. A second search was conducted on the Nationwide webs LILACS and BDENF, with combinations of two descriptors in Portuguese, separated by the boolean operator "and": assistance humanization and permanent education; assistance humanization and primary health care; permanent education and primary health care; assistance humanization and health staff; assistance humanization and health education. On the basis of this search 622 pieces came out, which, added to the results of the first search, reached 2,668 articles found.

After the reading of title and abstract, redundancies as well as those pieces not addressing the guiding question in this study were eliminated. Seven pieces came out, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Selection process flow for reality-based review. Source:

The writers (2016)

Evaluation of evidence quality comprisded the third step. To that end, articles found were evaluated, according to their quality in relation to the study question. Their science nature was not questioned granting their publication in scientific indexed journals with a classification treatment on the Brazilian periodicals evaluation system Qualis ensured inherent scientific nature7.

The fourth step translated data extraction. To that end, articles were read in full and organized on figures and tables, listing the following items: title, year, objective, type of study, context, intervention strategies, and main results7.

That organization was relevant to the synthesis of findings, the fifth step. It ensured identification of intervention strategies as well as7 .

The sixth step, dissemination of findings, shall be ensured on the basis of the dissemination of this article to managers and health workers within the scientific community after publication7.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

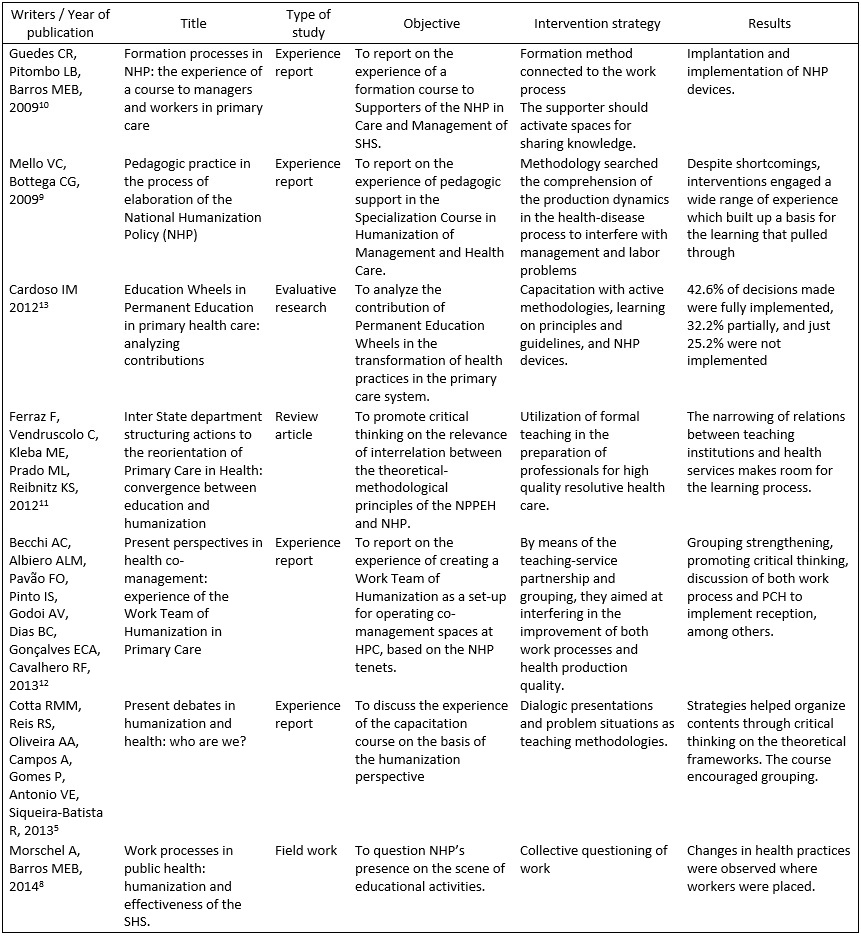

Concerning the study type, experience reports prevailed, showing the vicinity of the theme to health service practices and scholarship. They were published from 2009 to 2013, showing updating of publications on the issue, according to Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Context, intervention strategies and results achieved. . Brazil, 2016. Source: The writers (2016).

Concerning contents, six studies5,8-12 presented experience by professionals after humanization-related courses. Three out of those reported on experience related to the Institutional Supporters Formation Course5,9-10. The other three8,12-13 described experience of education actions with workers at health units. Just one publication11 promoted critical analysis on the structuring of Programs implanted by both the Health and the Education Departments, aiming at enhancing preparation of health professionals at PC (Figure 2).

In face of that analysis-based material (Figure 2), we were able to break down the syntheses of findings, listing intervention strategies ensuring both the NHP tenets and the definition of theories inherent to the theme later on.

Intervention strategies

Active learning methodologies as well as grouping in the articles5,8-10,12-13 were evinced in all articles of the study5,8-12 as relevant education interventions to implant and use NHP devices in PC.

Articles showed educational actions with active learning methodologies among professionals as interventions needed to the building up of humanized care.

Those studies showed dialogues and/or questioning practices as favoring tools on the active educational process, incorporating learning to the service routine, in such a way that problems experienced became background to discussions.

That was relevant to shed light on concrete practices by workers as well as to set up collective strategies to face daily challenges, anchoring the so-called significant learning, one of the principles at PHE14. The basis presumably sustaining that experience takes it as granted that the major challenge about the use of active methodologies lies in ensuring the student's self-reliance, in such a way that he/she can actively take part in the teaching-learning process, not just as an information duplicator, but rather as a critical individual, who can build up knowledge 15, as we have been discussing here.

In fact, effective educational processes must enhance participants' commitment to a practice fitted to user's needs, driven by the active pedagogic approaches. It is by critically going over yesterday's practice one can improve on the forthcoming one15.

Concerning grouping, articles enhanced it as a crucial intervention to the setting up of new labor arrangements which can allow for humanized management and care. It was possible to observe that individuals' participation in collective spaces within their action territory makes them co-accountable by an articulated and sound work process, a producer of assertive results over the health of the population assisted. Those were the major issues permeating discussions in the publications selected.

In that sense, there are a few dialogic territories suggested by the NHP, included in the co-management guidelines. Among them, the Work Team for Humanization is quoted in one of those experience reports12. It acts as a tool in subject constitution and organization, allowing for transformation and discontinuation into new possible modes and capable of critical engagement in the health realm10. The Wheel Method, quoted in a publication5, came out as an additional environment encouraging grouping. It is defined as a collective space of "supplies and demands" which, subject to daily analysis, turn into projects, tasks, and actions13.

Thus, a way to widen humanized practices consists of effective subjects' participation in decision making in health services17. Implementation of those co-management processes, like PHE, adds to the creation of a favorable design to humanization18. Thus, individuals' participation in discussion environment allows for their leading roles formulating new practices. For the condition that allows the move from a passive to a leading stand in the building up of their own knowledge is ensured by the exercise of participation, stimulated by active methodologies and enhancement of reality2 inherent to grouping processes.

In spite of that, a humanization concept based on principles of subjects' self-reliance and leadership has stood as one of the challenges of the NHP ever since its creation19.

Although the focus to this research has lain on the workers' participation in the construction of the NHP, it is granted that all those engaged in the process of health production must take active part to ensure the SHS effectiveness3. Two pieces of experience in this study 5,12 showed there was no significant participation by either management or users within the collective discussion territories. That runs contrary to the premise all subjects must exercise leading roles, as provided for by the NHP guidelines, which presupposes democratic management on the scenery of practices 20. Lack of engagement by those actors has constituted a major barrier to the building up of a care model concerned with the interest of those involved in the process, for that process must be guided by self-reliance and leadership values concerning the subjects involved, as well as by users' rights and collective participation in the management process21.

That observation, however, does not disqualify the assertions in the studies concerning the educational strategies in the implantation and strengthening of the NHP in PC. It just enhances the shortcomings to interest management among different leaders in the SHS.

There is an additional aspect to be highlighted about the publications here examined. Workers' participation in the building up of new practices runs contrary to the discussion elsewhere claiming local management is often characterized by lack of workers' self-reliance and participation in decision making as well as management verticalization22. On account of their participating and critical nature, the PHE processes this analysis examined might refute the usual characterization of local management exactly because they sustain a practice opposing passivity and blind obedience.

Leadership and self-reliance, therefore, are crucial to decision making based on active methodologies and collective knowledge as interventions capable of transforming professional practices, as set forth in the PHE guidelines3.

It is sustained that a fragile co-management and evaluation system of labor processes, which hold workers as the only ones accountable for either poor or good system operations does not enhance self-reliance and leadership in health production and gets in the way of implanting and ensuring new policies, actions, and practices10. Such fragility, still in the studies analyzed that left out additional SHS actors other than workers, has not been a reality we have taken in.

Theoretical framework

In face of those findings, it was possible to define theoretical frameworks that spell out PHE processes existing in PC for the implantation and use of NHP devices.

The first one was calledScholarship-Service Integration Favors Humanization in PC. It has been grasped that effective partnership between scholarship and services, tended by dialogic learning, turns out to be a possible and fit strategy to the implantation of NHP. All of the studies selected report on experience out of those partnerships, showing that the coming together of teaching institutions and health assistance can stimulate the production of a practice ripened by critical exercise.

All publications analyzed also evinced the several formative initiatives as well as educational actions set forth by the Health Department, teaching institutions and managers, in search for transformation of professionals' practices.

Those initiatives proved relevant because, as discussed in a few publications5,10-11, the health professional's education has been expressively concerned with the biomedical model, which encourages a fragmented process in health production, brought down to the binary opposition complaint-conduct and which cannot make professionals prepared to promote humanized care.

Therefore, there are shortcomings along academic formation which are topped by the lack of professionals with a profile to act in PC. From the learning and work stand, education deficiencies within the very health system, especially on the local level, are also concrete situations that reinforce distancing from more strongly humanized practices6.

Conversely, the very scholarly institutions that have educated unprepared professionals to the present demand for health services can help now with new perspectives in education, for the counter-mainstream nature in education and health has been assiduous to scholarship.

Therefore, the articulation between teaching institutions and health systems at specific moments helps professionals both with refreshing their knowledge and with the development of critical thinking as well as of their capacity to take social reality into account to improve health care2 It finally clarifies it is a partnership which favors humanization of PC.

As it attempts to maintain its curriculum structure, formal education has been able just to pass on information to students. It is just with professional practice that that educational process comes effectively into being from the PHE stand because it brings together concepts to be exercised in professional acting23, such as it is found in the reality-based synthesis under discussion.

This evidence allows us to highlight that formation must get to be managed collectively, and must get to be guided by the real health needs in our country, by means of effective articulation between teaching institutions and health system24. Such inference is especially timely in the context of education and professional formation in PC humanization, for teams' work processes undergo positive changes when they plunge in the significant learning realm, mediated by the approximation between service and scholarship25.

Entitled Dialoguing and Enhancement of the Participants Favors Humanization in PC, the second theory is based on the opening up of dialogic spaces at health units. It finds that the participation of social subjects of the formation square – workers, users, managers, and teaching institutions11, in those spaces, facilitates the implantation of the NHP devices in PC.

Regarded as a process mediated by interactive language, dialogue requires horizontal-like relations between those social subjects, by means of which interventions validity is directly related to the argumentative capacity to interact, and not to the political positions they occupy26. Along this way, dialogue favors learning, in the sense that it transforms usual practices.

Dialogic meetings presuppose the creation of possibilities to both produce and endow new meanings to the participants' experience, who engage as critical historic and social actors before reality27. It is within that exchange arena where the teaching-learning process occurs because people's diversity can prove to be an element of cultural wealth which helps with learning and transformation processes28. In critical education all have active participation in the teaching-learning process29.

Therefore, in face of the range of different knowledge by professionals in PC, by population, and by management, dialogic spaces are context-oriented learning spaces and turn PHE into a possible tool for critical analysis of daily problems and the search for solutions.

CONCLUSION

We have enhanced two relevant theoretical frameworks which suggest the positive relation between PHE and humanization in PC: the first entitled Scholarship-Service Integration Favors Humanization in PC, which highlights the partnership of teaching institutions and PC for the materialization of NHP; and the second, Dialoguing and Enhancement of the Participants Favors Humanization in PC , which highlights the enhancement of dialogue spaces as a major scenario for the development of that Policy.

We have argued that with those two theoretical frameworks workers at PC are accessible to the implantation of NHP devices. Leading roles and self-reliance have permeated discussions in the publications analyzed in this study and can be identified as core factors to the materialization and success of interventions.

Thus, we can suggest that to make PHE and humanization in PC effective, there must be a constant challenge about encouraging teams into critical thinking as well as a structuring of a local health policy anchored in collective participation and construction. That shall certainly affect the strengthening of PHE and other health policies which require changes in work process.

As a limitation to this study, the restricted number of research pieces found in the literature on the theme stands out, a shortcoming to the broadening of discussions.

REFERENCES

1.Celedônio RM, Jorge MSB, Santos DCM, Freitas CHA, Aquino FOTP. Políticas de educação permanente e formação em saúde: uma análise documental. Rev da Rede Enferm do Nord [Internet]. 2012; 13(5): 1100–10. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.revistarene.ufc.br/revista/index.php/revista/article/view/1165

2.Amestoy SC, Milbrath VM, Cestari ME, Thofehrn MB. Educação permanente e sua inserção no trabalho da enfermagem. Ciência, Cuid e Saúde. 2008; 7(1): 83–8.

3.Brasil. Educação permanente em saúde: um movimento instituinte de novas práticas no Ministério da Saúde [Internet]. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria-Executiva. Subsecretaria de Assuntos Administrativos. Brasília; 2014. 120 p. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/educacao_permanente_saudemovimento_instituinte.pdf

4.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Cadernos HumanizaSUS [Internet]. Caderno Humanizasus. 2010. 242 p. p. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cadernos_humanizaSUS.pdf

5.Cotta RMM, Reis RS, Campos AO, Gomes AP, Antonio VE, Siqueira-Batista R. Debates atuais em humanização e saúde: quem somos nós? Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2013; 18(1): 171-9. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/csc/v18n1/18.pdf

6.Silva LA, Casotti CA, Chaves SCL. A produção científica brasileira sobre a Estratégia Saúde da Família e a mudança no modelo de atenção. Cienc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2013; 18(1): 221-32. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v18n1/23.pdf

7.Tractenberg L, Struchiner M. Revisão realista: uma abordagem de síntese de pesquisas para fundamentar a teorização e a prática baseada em evidências. Cienc da Inf. 2011; 40(3): 425-38.

8.Morschel A, Barros MEB. Processos de trabalho na saúde pública: humanização e efetivação do Sistema Único de Saúde. Saude soc. [Internet]. 2014 [access on Oct 20 2016]; 23(3):928-941. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-12902014000300928&lng=en

9.Mello VC, Bottega CG. A prática pedagógica no processo de formação da Política Nacional de Humanização (PNH). Interface (Botucatu) [Internet]. 2009 [access on Oct 20 2016]; 13(suppl 1): 739-745. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-32832009000500025&lng=en

10.Guedes CR, Pitombo LB, Barros MEB. Os processos de formação na política nacional de humanização: A experiência de um curso para gestores e trabalhadores da atenção básica em saúde. Physis [Internet]. 2009; 19(4): 1087–109. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/physis/v19n4/v19n4a10.pdf

11.Ferraz F, Vendruscolo C, Kleba ME, Prado ML, Reibnitz KS. Ações estruturantes interministeriais para reorientação da atenção básica em saúde: Convergência entre educação e humanização. Mundo da Saude [Internet]. 2012; 36(3): 482–93. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/artigos/mundo_saude/acoes_estruturantes_interministeriais_reorientacao_atencao.pdf

12.Becchi AC, Albiero ALM, Pavão FO, Pinto IS, Godoi AV, Dias BC, Gonçalves ECA, Cavalhero RF. Perspectivas atuais de cogestão em saúde: vivências do Grupo de Trabalho de Humanização na atenção primária à saúde. Saude soc. [Internet]. 2013 [access on Oct 20 2016]; 22(2): 653-660. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-12902013000200032&lng=en

13.Cardoso IM. Rodas de Educação Permanente na atenção básica de Saúde: analisando contribuições. Saúde soc. 2012; 21(1):18–28.

14.Sampaio J, Pinho IPM, Miranda TTL, Silva MA. Contribuições do Pet – Saúde, eixo Educação Permanente (EP) para os processos de trabalho do Centro de Atenção Integral à Saúde do Idoso em João Pessoa. Rev Bras Ciências da Saúde [Internet]. 2014; 18(Supl1): 69–76. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs2/index.php/rbcs/article/view/20944/11847

15.Freire P. Pedagogia da Autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. 48ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2014.

16.Paulon SM, Flach GA, Eich M, Coelho DL. Apoiar , intervir e agenciar: dos diferentes usos dos dispositivos da Política Nacional de Humanização na perspectiva dos apoiadores em formação. Saúde e Transform Soc [Internet]. 2014; 5(2):909. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/sts/v5n2/5n2a11.pdf

17.Nora CRD, Junges JR. Politica de humanizacao na atencao basica: revisao sistematica. Rev Saude Publica. 2013; 47(6):1186-200.

18.Cunha PF, Magajewski F. Gestão participativa e valorização dos trabalhadores: avanços no âmbito do SUS. Saude e soc [Internet]. 2012; 21(suppl.1):71–9. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/sausoc/v21s1/06.pdf

19.Verdi M, Finkler M, Matias MCS. A dimensão ético-estético-política da humanização do SUS: estudo avaliativo da formação de apoiadores de Santa Catarina (2012-2014). Epidemiol e Serviços Saúde [Internet]. 2015; 24(3): 363-72. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-96222015000300363&lang=pt

20.Nobre MT, Melo LE, Souza KO, Santana, LRO, Ribeiro LTA. Política Nacional de Humanizaçao na rede estadual de saúde pública de Sergipe. Rev Extensão Univ da UFS. 2013; 1(2):171–82.

21.Amarante DS, Cerqueira MA, Castelar M. Humanização da saúde pública no Brasil. Discurso ou recurso? Rev Psicol Divers e Saúde. 2014; 2(1): 6873.

22.Schimith, MD, Brêtas ACP, Budó MLD, Alberti GF, Beck CLC. Gestão do trabalho: implicações para o cuidado na atenção primária à saúde. Enfermería Glob [Internet]. 2015; (38):190–204. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/viewFile/194371/174091

23.Merhy EE. Educação permanente em movimento - uma política de reconhecimento e cooperação, ativando os encontros do cotidiano no mundo do trabalho em saúde , questões para os gestores, trabalhadores e quem mais quiser se ver nisso. Saúde em Redes [Internet]. 2015;1(1):7-14 [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://revista.redeunida.org.br/ojs/index.php/rede-unida/article/view/309

24.Azevedo BMS, Ferigato S, Souza TP, Carvalho SR. A formação médica em debate: Perspectivas a partir do encontro entre instituição de ensino e rede pública de saúde. Interface- Comunic. Saúde, Educ. [Internet]. 2013; 17(44): 187–99. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/2012nahead/aop5412.pdf

25.Brehmer LCF, Ramos FRS. Experiências de integração ensino-serviço no processo de formação profissional em saúde: Revisão integrativa. Rev. Eletr. Enf. 2014; 16(1): 228–37.

26.Rojas HL. Educación dialógica. UCV - Sci. 2010; 2(1): 69-77.

27.Silva MA, Santos MLM, Bonilha LAS. Limites e potencialidades das rodas de conversa no cuidado em saúde: uma experiência com jovens no sertão pernambucano. Interface Commun Heal Educ [Internet]. 2014; 18(48): 75-86. [access on Oct 20 2016]. Avaliable from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/v18s2/1807-5762-icse-18-s2-1299.pdf

28.Jiménez BR. Nuevos movimientos sociales en el estado español: una visión desde los principios del aprendizaje dialógico. Rev Int y Multidiscip en ciencias Soc. 2014; 2(3): 273–96.

29.Viana MRP, Moura MEB, Nunes BMVT, Monteiro CFS, Lago EC. Formação do enfermeiro para prevenção do câncer de colo uterino. Rev. enferm. UERJ, 2013; 21(esp.1): 624-30.