(*) SD = Standard deviation (**)LTIE = Long-Term Institutions for the Elderly

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Older adults with intellectual disabilities: sociodemographic characteristics, clinical conditions and functional dependence

Juliana Balbinot Reis GirondiI; Fernanda FelizolaII; Jordelina SchierIII; Karina Silveira de Almeida HammerschimdtIV; Luciara Fabiane SeboldV; José Luis Guedes dos SantosVI

I

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Brazil.

E-mail: juliana.balbinot@ufsc.br

II

Physiotherapist. Specialist in Health Care for the Elderly. Association of

Parents and Friends of Persons with Special Needs of Florianópolis. Brazil.

Email:

fernanda_felizola@hotmail.com

III

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Brazil.

E-mail: nina.schier@gmail.com

IV

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Brazil.

E-mail: karina.h@ufsc.br

V

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Brasil.

E-mail: fabiane.sebold@ufsc.br

VI

Nurse. PhD in Nursing. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Brasil.

E-mail: jose.santos@ufsc.br

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2018.22781

ABSTRACT

Objective: to describe the sociodemographic characteristics, clinical conditions and level of functional dependency of adults aging with intellectual disabilities (IDs). Method: this descriptive study, conducted in 2015 at a living-in center of an institution in south Brazil, was approved by the research ethics committee of Santa Catarina Federal University. Data were collected by assessment form and the Modified Barthel Index (MBI), and analyzed using descriptive statistics. Results: the participants were 54 people with IDs aged 45 years or more, 77.8% with moderate DIs, of average age 48.19 years and 57.4% female. The MBI reported 83.3% as mildly dependent, although requiring command or some type of support and supervision. Conclusion: care for persons aging with DIs requires technologies implemented on an inter-professional approach and respecting their individualities, so as to maintain their autonomy and independence.

Descriptors: Intellectual deficiency; aging; frail elderly; nursing.

INTRODUCTION

Demographic aging is a global reality that affects people with disabilities as well. In Brazil, 23.9% of the population has some type of disability or impairment, which represents about 45.6 million people. As for the type of impairment, the visual one reaches 35,774,392 people, the hearing - 9,717,318 people, the motor disabilities - 13,265.99 and 2,611,536 people have intellectual/mental disability1.

People with intellectual disabilities are those with lower than average intellectual functioning and with limitations in adaptive functioning in at least two instrumental abilities: self-care, communication, sociability, use of community resources, academic life, professional life, health, safety and leisure2.

Since aging with physical and social independence is already a challenge, disabled aging becomes an even more complex process3.

Thus, adequate care for the aging intellectually disabled persons is an important issue to be debated among health professionals. In this sense, despite the growth in the number of scientific studies on aging, in the last decades, there are still few published studies on the aging process among elderly people with disabilities. Therefore, there is a lack of information about the health conditions of intellectually disabled persons, which end up favoring the continuity of various social problems4 . Studies regarding the identification and health-disease characteristics of people with intellectual disabilities are important both for advancement in this area of knowledge and for the production of evidence for best care practices5.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to describe the sociodemographic characteristics, clinical conditions and level of functional dependence of people with aging intellectually disabled people.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The major health-related challenges arising from population aging are prevention, health maintenance, independence and autonomy, and delaying diseases and frailty. The organization of the Brazilian health system needs to be adjusted for the different demographic and epidemiological profiles resulting from this increase, since the magnitude of the increased health spending with the elderly population will depend, above all, of those remaining years to be healthy or free of illnesses and dependencies. Thus, functional capacity emerges as the most appropriate health concept to qualify and operationalize a health care policy for the elderly. This policy should therefore aim to maintain the maximum functional capacity of the aging individual for as long as possible6.

In this context, it is crucial to consider that independence and autonomy involve social and economic aspects and, more markedly, the physical and mental abilities necessary to carry out the activities of daily living (ADL) adequately and without the need for help4-6.

People with disabilities, often due to limitations arising from physical, sensory or intellectual disabilities, have some degree of dependence. Such limitations may lead to restrictions on functional capacity, thus requiring adaptations in the environment and provision of support to maintain this autonomy4,5.

Although technological advances in the health area and the social inclusion process have contributed decisively to increasing the quality of life and the longevity of people with disabilities, the aging process has taken place earlier. However, there is no consensus regarding the chronological age from which a disabled person should be considered elderly, since each pathology presents particularities and a specific life expectancy. There is national and international scientific evidence that people with intellectual disabilities, especially those with Down Syndrome, present early aging7.

Literature sources have indicated that among people with intellectual disabilities signs of aging appear around the age of 30 due to prolonged use of medications, mainly neuroleptics and anticonvulsants. These medications cause secondary health problems, such as demineralization, osteoporosis, and movement disorders, which compromise mobility and decrease muscle strength8. For legal purposes, in Brazil, the Law Project No. 1118, of 2011, establishes that the person with a disability is considered elderly when he or she is 45 years of age or older. This change takes into account that the life expectancy of these people is not the same as those without disabilities9.

In view of this situation, the need to know and recognize the clinical and functional characteristics of intellectual disability is contemporary and extremely important, since it is necessary to understand the symptoms to explore the mechanisms and dynamics that interfere with behavior and conduct of disabled persons4.

METHODOLOGY

This is a descriptive, quantitative approach developed in a community center of an Association of Parents and Friends of Persons with Special Needs (APAE) in southern Brazil.

The selected population for the study was composed of 60 aging intellectually disabled persons of the APAE Social Center. The following inclusion criteria were men and women aged 45 years and older and diagnosed according to ICD-10 for intellectual disability (F70-F79), associated or not with another disability, which are also the main eligibility criteria for participation of the activities in the said institution. Individuals who had consecutive absences that made it difficult and/or impossible the application of the instruments during the period of data collection were excluded. Thus, the study sample consisted of 54 participants, equivalent to 90% of the population accessed.

Data collection was performed from January 1 to April 31, 2015, at the facilities of APAE. For the data collection, we used non-participatory observation, consultation in medical records; the clinical evaluation form developed by one of the researchers and the application of the Modified Barthel Index (MBI).

At first, people were observed in their daily activities at the institution by one of the researchers, who analyzed their initiatives, decisions, motor conditions, cognitive conditions and limitations, recording the findings in the clinical assessment form, in line with MBI. In the second stage, the researcher analyzed documents (patient records and online registration system used in the investigated institution) to obtain sociodemographic characteristics. The variables selected were: gender, age, schooling, marital status, occupation, time and reasons for institutionalization, as well as social support.

In the third stage, for the clinical characterization of the sample, we collected the anthropometric variables: height, mass, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference. Next, the MBI evaluation was performed. During the evaluation of the parameters of basic activities assessed by this index, people were asked to perform tasks, receiving constant commands and guidelines to perform such activities.

The MBI uses a scoring system ranging from 10 to 50, with a response scale of one to five points for each item, increasing sensitivity in detecting changes. This instrument assesses 10 basic activities of daily living: feeding, grooming, toilet use, bathing, bowel control, bladder control, dressing, bed-chair transfer, stairs, walking or wheelchair handling (alternative for walking). For this analysis, we used the absolute values (from 1 to 5) of each domain (1 corresponds to totally dependent for the given domain, 5 corresponds to totally independent for the given domain). The classification is according to the obtained scores, as follows: totally independent (score 100), mild dependence (score 99 to 76), moderate dependence (score 75 to 51), severe dependence (score 50 to 26) and totally dependent (score ≤ 25)10.

The results were processed and tabulated in the Statistic Package for Social Science, version 20.0. For the treatment of the data, we chose the descriptive statistics, with relative and absolute numbers, and the results are presented in table form.

The study is linked to the macroproject entitled The health care and social support network for elderly people with disabilities in the greater Florianópolis area and the care technologies , approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research with Human Beings of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, under number 24410513.5.0000.0121. All the ethical principles established by Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council were respected.

RESULTS

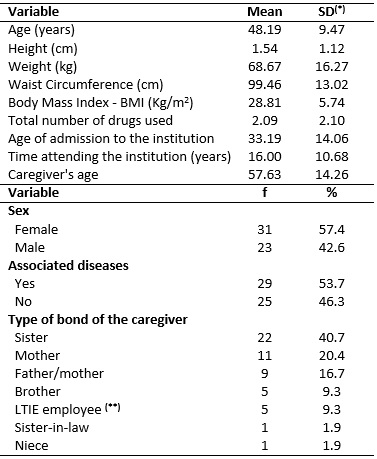

Fifty-four people with intellectual disabilities and experiencing the aging process participated in the study; most (57.4%) were women and with an average age of 48 years. Regarding the time of bonding with the institution, the age of admission was around 33 years and they had been attending it for 16 years. In addition to intellectual disability, 57.4% of the participants also had other associated diseases. Regarding the care provided to the aging person, women were the majority among the caregivers, especially sisters (40.7%) and mothers (20.4%). Table 1 shows all parameters analyzed in relation to the sociodemographic and health profile of the research members.

TABLE 1:

Sociodemographic and health profile of participants. Florianópolis/SC,

Brazil, 2015. (N=54)

(*)

SD = Standard deviation (**)LTIE = Long-Term Institutions for the Elderly

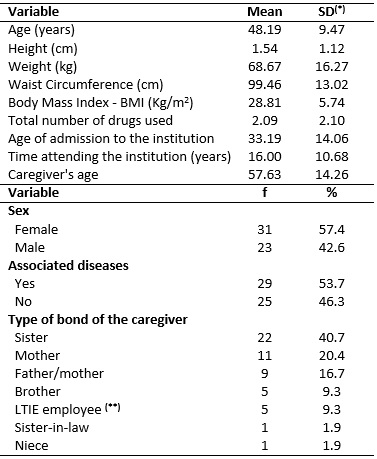

Table 2 shows the results related to the diagnostic investigation and the MBI. We highlight the prevalence of individuals with diagnosis of moderate intellectual disability (77.8%) and with undetermined etiology (51.9%). Visual impairment (20.4%), hearing impairment (14.8%) and arterial hypertension (13%) were the main associated diseases. The evaluation of the basic activities of daily living, through MBI, showed that 83.3% of the participants presented mild dependence according to Table 2.

TABLE 2:

Clinical Variables and Modified Barthel Index. Florianópolis/SC, Brazil,

2015. (N=54)

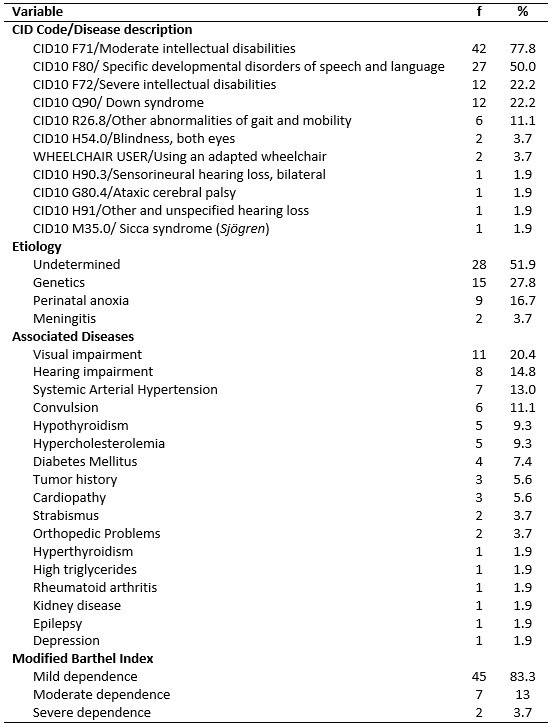

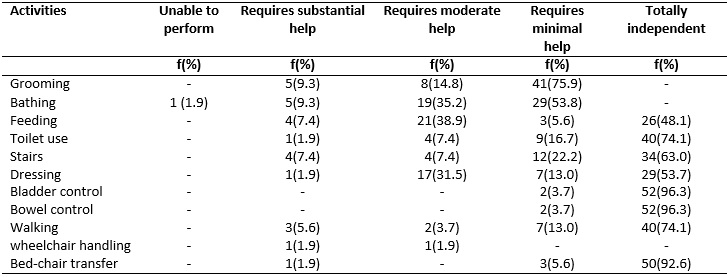

Table 3 describes the results regarding the basic activities measured by MBI. In the item independence, the activity with the highest prevalence was the bladder and bowel control (96.3%). Grooming was the activity in which the majority demanded minimal help (75.95%). Feeding (38.9%) demanded the most moderate help. Still, grooming and bathing (9.3%) demanded more substantial help, according to Table 3.

TABLE 3:

Basic activities measured by MBI. Florianópolis/SC, Brazil, 2015. (N=54)

DISCUSSION

In this study, there was prevalence of elderly female participants (57.4%), a result also registered in other studies with institutionalized elderly 11-14. In relation to age, there was an average of 48 years, which indicates an early aging process among the studied population.

Regarding the care provided to the aging person, it was predominantly performed by the sister (40.7%) or mother (20.4%) of the study participants. Regarding the age of the caregiver, the average was 57 years. These findings are corroborated by a study in which the caregivers were mostly women (83.3%), mothers (56.1%), and the mean age was above 50 years 7. International research studied Colombian families with adults with intellectual disabilities and aged between 23 and 55 years, and also identified the prevalence of women as primary caregivers (93%), mainly mothers (65.2%)13.

Care provided to a person born with an intellectual disability extends throughout life and is mainly performed by the parents, with a view to long-term dedication. These permanent and prolonged care become more difficult to perform because, over the years, the caregiver also ages and experiences physical and mental exhaustion7. Thus, as they grow older, the needs of the individual and their family members change. In most cases, parents are no longer able to provide adequate care, and it is often difficult to distinguish who cares for whom12. However, as parents grow older and become dependent or die, the support of siblings or other relatives remains3.

The family was and continues to be the nucleus of intergenerational solidarity par excellence, playing an essential role in restoring and maintaining the health and well-being of its members by providing support in situations of dependence and need for care14. Thus, in order to seek a comprehensive and humanized care, one must consider the particularities and complexities of the person in question, and structure, reflect and use in a cohesive way the knowledge developed in order to offer adequate care with assistance strategies for the needs of the person through the implementation of appropriate care technologies for this clientele.

Regarding the clinical conditions, there was an average BMI of 28.81, indicating that the participants are above their ideal weight. The values and meanings of BMI (kg/m2) are: <18.5 for low weight; 18.5 to 24.9 for normal weight; 25 to 29.9 for overweight and> 29.9 for obesity15. BMI is one of the nutritional status indicators most used in population studies, associated or not to other anthropometric variables, obtained from weight and height16. Obesity is a public health problem in more developed countries and adult individuals with intellectual disabilities appear to have a higher obesity rates than the general population, especially women17.

The average waist circumference of the participants was 99.46 cm, which is considered high for females. Waist circumference was obtained using a non-extensible measuring tape, positioned immediately above the umbilical scar, and reading was done at the time of participants' expiration. For classification, we used the cut-off points proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program, which indicates cardiovascular risk for values ≥ 102 cm for men and ≥88 cm for women18.

Similar results regarding BMI and overweight were described in a study with institutionalized elderly in Fortaleza/CE. Problems associated with the nutritional status of the elderly can accelerate the appearance of fragilities and vulnerabilities, making it difficult for the elderly to recover and significantly reducing their life span, especially in the presence of chronic diseases19.

Systematic review of early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities has shown that the life expectancy of people with intellectual disabilities is 20 years lower than the general population in high-income countries. Respiratory and circulatory diseases are the most common underlying causes of death and are probably preventable in some cases5. Chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and cancers are risk factors since childhood among intellectually disabled persons due to the high prevalence of sedentary lifestyle20-22. Thus, such anthropometric findings can be related to the life habits of this population, highlighting the prolonged idle time, as observed in the daily routine of care of these people.

Another aspect evidenced in the present study is that 53.7% of the participants had some associated disease, with emphasis on visual impairment (20.4%) and hearing impairment (14.8%). Of all senses, vision and hearing are the most affected, since they decrease their acuity, which influences, among other aspects, the postural control and the balance, constituting a barrier for the relationship of the elderly with their environment23, 24.

Regarding the clinical diagnosis, there was a predominance of moderate intellectual disability (77.8%) among the people evaluated in this study. However, despite the differentiation between levels of dependency, in general, all participants are totally dependent on commands and guidance for the activities performed.

The presence of functional disabilities in the elderly has become an important public health problem, considering the impact they have on the life of the individual, the family and health services. Therefore, it is the health professionals' responsibility to identify early functional disabilities and the factors associated with them, and therefore, the overall evaluation of the elderly should be routine in health services, from primary care to the most complex levels of care25,26.

Regarding functional dependence, the present study found a high number of people with mild dependence (83.3%). This data is directly associated not only with the performance of the person in accomplishing such task, but with the command and orientation carried out in first place. The evaluation of the functional capacity of the elderly makes it possible to intervene, through health promotion, with specific actions that contribute to prevent disabilities, allowing nurses and other health professionals to draw up a specific care plan for each elderly person, based on the results of the instruments used to measure functional capacity27.

Therefore, the participants of this study presented greater difficulty in performing more complex activities, which require greater coordination and reasoning, showing better performance in global activities. In this context, their dependence seems to be tied to the behaviors of those around them, which often end up aggravating dependence rather than promoting/encouraging autonomy. In general, there is a mismatch between the capacities and demands of the context in which people with intellectual disabilities are inserted. Thus, the main barrier seems to be the lack of adequate stimuli. Impatience with teaching and self-care skills training stems from lack of information and inadequate structuring of clinical, therapeutic, pedagogical and family strategies for loss prevention and maintenance of acquired skills. After all, these skills are crucial when it comes to people with intellectual disabilities and experiencing the aging process because the requests made to them demand more waiting time so that the answers happen7.

The importance of understanding the needs, demands, abilities and potentialities of each person with intellectual disability and undergoing the aging process is relevant, not only by the professionals who work with them, but also by the families. This can contribute to the reduction of socio-environmental adversities and enable the investment in new technologies of care to improve health conditions and reduce the level of dependence.

In this context, there must be focus on programs and services aimed at promoting health, quality of life and development of autonomy and independence. Such devices must be permeated with manual and occupational activities, periodical physical exercises, artistic and entertainment activities. These actions comprise the prevention and maintenance of skills and will contribute to the empowerment of the person with intellectual disability experiencing the aging process7.

The nature of the support systems is varied and influenced by the individual, family, friends, informal network and specialized services provided by public health policies, social assistance or organizations that deal with intellectually disabled persons28. In this sense, health professionals should be qualified to provide care for the elderly, aiming at healthy and quality aging29. In this perspective, they may find support in resources and strategies to promote the development, education, interests and social well-being of people with disabilities, including people with intellectual disabilities, also contributing to the process of self-determination and social inclusion.

CONCLUSION

The sociodemographic and clinical profile of the study participants is characterized mainly by women, with moderate intellectual disability and other associated diseases, being assisted by female caregivers.

Although the MBI final score was predominantly of mild dependence, these people are totally dependent on commands, guidance, or some oversight to perform the activities. These difficulties focus, to a greater degree, in the execution of complex activities, which require greater coordination and reasoning.

This research fosters reflections on the need to develop care strategies based on the potential of these people, highlighting the importance of the multidimensional approach, focused on changes in the evaluation process. This perspective provides a comprehensive vision of care, outlined in individual and environmental needs and in different dimensions correlated with appropriate levels of support.

The application of the MBI assessment can be useful to detect the most disabling limitations of aging intellectually disabled people, associated or not with other disabilities. However, it is necessary to develop other instruments for a more reliable detection of the limitations of these people.

The convenience sample and the link of the participants to a specific care setting were the limitations of the present study. Thus, there is the need of further studies to elucidate the subjective issues involved in the health and disease process of this population group and to provide subsidies for improving the work of health and nursing professionals.

REFERENCES

1. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics IBGE. Demographic Census of 2010. [cited in May 14, 2017] Available from: http://www.censo2010.ibge.gov.br

2.Santos FHS, Dota FP. Professional inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities: a matter of autonomy. In: Guilhoto L, Organizadores. Aging and intellectual disability: a silent emergency. 2nd ed. São Paulo: São Paulo APAE Institute; 2013. p. 117-32.

3.Marin MJS, Lorenzetti D, Chacon MCM, Polo MC, Martins VS, Moreira SAC. The living and health conditions of disabled people over 50 and their caregivers in a municipality of São Paulo. Rev. bras. geriatr. gerontol. 2013; 16(2):365-74.

4.Girardi M, Portella MR, Colussi EL. Aging in the intellectual disabled persons. RBCEH. 2012; 9(Supl. 1):79-89.

5.O'Leary L, Cooper S‐A, Hughes‐McCormack L. Early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect Disabil. 2018;31:325-42.

6.Veras RP. Strategies for coping with chronic diseases: a win-win model. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2011; 14(4):779-86.

7.Hayar MA. Aging and intellectual disability: the family caregiver as protagonist in the care of the elderly. Fed. Nac. das Apaes- Fenapaes. 2015;2(2):40-52.

8.Pimenta RA, Rodrigues LA, Greguol M. Evaluation of quality of life and overload of caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities. Rev. Bras. Ciên. Saúde. 2010;14(3):69-76.

9. Federal Senate (Br). Law Project No. 1118, of 2011. It establishes that the person with a disability is considered elderly when he is 45 years of age or over. [cited in May 14, 2017] Available from: https://legis.senado.leg.br/sdleg-getter/documento?dm=4451474

10.Cincura C, Pontes-Neto OM, Neville IS et al. Validation of the national institutes of health stroke scale, modified ranking scale and Barthel index in Brazil: the role of cultural adaptation and structured interviewing. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2009; 27(2):119-22.

11.Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA, Schwartz JB. Age and sex variation in prevalence of chronic medical conditions in older residents of U.S. Nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012;60(4):756-64.

12.Aguilella AR, Alonso MV, Gómez CS. Family quality of life and supports for parents of ageing people with intellectual disabilities. Siglo Cero. 2008;39(3):19-34.

13.Córdoba L. Families of adults with intellectual disability in Cali, Colombia, using the model of quality of life. Psykhe. 2007;16(2):29-42.

14.Sebastião C, Albuquerque C. Aging and dependence: a study on the impact of dependence of an elderly member in the family and in the primary caregiver. Revista Kairós Gerontologia. 2011;14(4):25-49.

15.Calazans FDCF, Guandalini VR, Petarli GB, Moraes RAG, Cuzzuol JT, Cruz RP. Nutritional screening in surgical patients at a university hospital in Vitória, ES, Brazil. Nutr. Clín. Diet. Hosp. 2015;35(3):34-41.

16.Menezes TN, Brito MT, Araújo TBP, Silva CCM, Nolasco RRN, Fische MATS. Anthropometric profile of elderly residents in Campina Grande-PB. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2013;16(1):19-27.

17.Sousa GR, Pinto MG, Seeber JR, Silva DAS. Association between nutritional status and health-related physical fitness in adults with intellectual disability. Rev. Bras. Educ. Fís. Esporte. 2015;29(4):543-50.

18.Cardoso AS, Gonzaga NC, Medeiros C, Carvalho DFD. Relationship between uric acid and components of metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis in overweight or obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2013;89(4):412-8.

19.Borges CL, Silva MJ, Clares JWB, Nogueira JM, Freitas MC. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of institutionalized elderly: contributions to nursing care. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2015;23(3):381-7.

20.Rimmer JH, Yamaki K, Davis BM., Wang E, Vogel LC. Obesity and overweight prevalence among adolescents with disabilities. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2011; 8(2):1-6.

21.Mendonça GV, Pereira FD, Fernahall B. Effects of combined aerobic and resistance exercise training in adults with and without Down syndrome. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011;92(1):37-45.

22.Frey GC, Temple VA. Health promotion for Latin Americans with intellectual disabilities. Salud Publ. Mex. 2008; 50(2):167-77.

23.Azeredo Z. Individual aging. In: Azeredo Z, organizer. Elderly as a whole. Viseu(Pt): Psicosoma; 2011. p. 45-76.

24.Sequeira C. Providing care for the elderly with physical and mental dependence. Lisboa(Pt): Lidel; 2010.

25.Brito KQD, Menezes TN, Olinda RA. Functional disability and socioeconomic and demographic factors in elderly. Rev. bras. enferm. 2015; 68(4):633-41.

26.Bitencourt GR, Felippe NHMD, Santana RF. Nursing diagnosis impaired urinary elimination in the elderly in the postoperative period: a cross-sectional study. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2016; 24(3): e16629.

27.Santos GS, Cunha ICKO. Functional capacity and its measurement in the elderly: an integrative review. REFACS (online). 2014; 2(3):269-78.

28.Verdugo MA, Gómez LE, Arias B, Navas P, Schalock RL. Measuring quality of life in people with intellectual and multiple disabilities: validation of the San Martín Scale. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014;35(1):75-86.

29.Rigon E; Dalazen JVC, Busnello GF, Kolhs M,Olschowsky A, Kempfer SS. Experiences of the elderly and health professionals related to care by the family health strategy. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2016; 24(5):e17030.