Note: More than one response was given by each interviewee.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Women with breast cancer in adjuvant chemotherapy: assessment of quality of life

Laís de Andrade Martins CordeiroI; Denismar Alves NogueiraII; Clícia Valim Côrtes GradimIII

I

Nurse. Master in Nursing, Federal University of Alfenas. Minas Gerais

Brazil. E-mail: laandradema@yahoo.com.br

II

Statistician. PhD in Statistics and Agricultural Experimentation. Adjunct

Professor, Federal University of Alfenas. Minas Gerais Brazil. E-mail:

denismar@unifal-mg.edu.br

III

Nurse. Post-doctor. Full Professor, Federal University of Alfenas. Minas

Gerais Brazil. E-mail: cliciagradim@gmail.com

IV

Excerpt from the dissertation:

"Women with breast cancer under chemotherapy or hormone therapy:

quality of life assessment".

V

Acknowledgements to the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Level

Personnel, for granting of financial support to the study.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12957/reuerj.2018.17948

ABSTRACT

Objective: to evaluate the quality of life of women with breast cancer in adjuvant chemotherapy. Method: this descriptive, quantitative, cross-sectional study examined 25 women undergoing treatment at a High Complexity Oncology Unit in a Brazilian city, in 2012, using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Breast plus Arm Morbidity (FACT B +4) questionnaire. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Alfenas Federal University (UNIFAL-MG), under Protocol 208/2011. Results: by and large, good quality of life was found in the domains and for Total FACT B. Lower mean scores were observed in the additional concerns with breast cancer (22.68 ± 4.96/36) and functional well-being (16.92 ± 4.60/28) domains. Conclusion: the findings highlighted the need for care relating to changes in body image, disease-related stress and anxiety that a family member may come to have cancer.

Descriptors: Quality of life; breast neoplasms; drug therapy; women's health.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical manifestations resulting from the therapeutics of breast cancer determine the conduct adopted by health professionals, in order to prevent negative impacts to patients, promote health and humanize the provision of care.

Actions developed by nurses stand out as acts of responsibility in the incessant search for harmony in the quality of life (QoL) of women. The World Health Organization, defines quality of life as "the individuals' perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns"1:1405.

The measurement of this construct is characterized as a relevant instrument favorable to the evaluation of the impact of diseases on patients and allows the creation of indicators of severity and evolution of a disease 2.

In order to provide public health care, the analysis of patients' QoL is important to a better targeting of services in order to benefit the population3. Thus, QoL assessment allows professionals to analyze the different aspects of the patients which may or may not have been modified before the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

In this context, in order to help health professionals to identify patients with breast cancer and which are the dimensions of life that may be negatively affected by chemotherapy (CT), the present studyIV aimed to evaluate the QoL of women with this pathology undergoing adjuvant chemotherapeutic treatment in a city in the countryside of southern Minas Gerais, Brazil.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The experience of breast neoplasia is surrounded by a situation that encompasses the tendency to develop low self-esteem, to feel discrimination and stigmatization by society, and also the need for a redefinition of life projects4.

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer have repercussions throughout the patients' body and this causes a permanent or transient change of certain social roles and activities5. Thus, it is known that the triggering of CT-related adverse events is intertwined with subjectivities that describe the patients' profile and the clinical picture of the disease.

After a long postoperative period, care is still needed due to physical, social, economic, psychological and spiritual changes experienced by women. Such care aims at positive actions to promote QoL6.

In face of the changes imposed by breast cancer and CT, there is an imperative need for care to prevent damage, in order to allow the achievement of well-being favorable to all the contexts that delineate the holistic being of the patients. To this end, QoL assessment has approved to be a strategy to raise reflections about the interventions that must be planned and executed to reach a better coping with the obstacles that the women start to face.

METHODOLOGY

A descriptive, cross-sectional study with a quantitative approach was developed with breast cancer patients under adjuvant CT in a High Complexity Oncology Care Unit (UNACON) located in a city in the countryside of southern Minas Gerais, Brazil.

The sample consisted of 25 women selected who met the inclusion criteria pre-determined in the study: women undergoing breast surgery for treatment of cancer; being under CT at the UNACON; cancer stage 0, I, II or III; being oriented in time, space and, ability to communicate verbally. Patients with breast reconstruction, undergoing radiotherapy, with metastases in other parts of the body, or with a history of cancer other parts of the body were excluded.

The women attended UNACON to undergo CT or for consultations with subsequent scheduling of the therapeutic session. The interviews were performed at the unit while the patients awaited the start of the chemotherapy session. In order to avoid sample losses, in the case of patients who performed the session in other days than that of the medical consultation, the instrument for patient identification was applied in the first contact, and the instrument for QoL assessment was applied on the day scheduled for the CT session as well as the measurement of the arm circumference.

We used interviews for identification of participants with questions addressing socio-demographic, clinical and therapeutic data. After the interviews, the clinical and therapeutic characteristics were confirmed by consulting the results of exams and consultation and follow-up reports attached to the women's medical chart.

The variables collected in this study were: age group; presence of companion; active sex life; presence of children; religious belief; schooling; type of surgery; time elapsed after surgical treatment; laterality; histological grade; tumor staging; axillary lymphatic involvement; lymphedema; quantity of prescribed chemotherapy cycles; number of cycles performed; adverse events of chemotherapy.

The measurement of arm circumference was performed in both limbs to verify the presence of lymphedema in the limb homolateral to the surgery. A metric tape was used for measurements, with accuracy of 0.1 centimeter and use of eight reference points in each upper limb, for later comparison of values. The points were demarcated as follows: cubital fossa (considered the point zero); two points in the supine position, with intervals of seven centimeters and one point to the height of the axillary line. In the forearm, the point zero was taken as a reference and, from that point, two points with intervals of seven centimeters were marked. Wrist and hand measurements were also used.

In the measurement of the arm circumference, the presence of lymphedema was indicated when there was a difference of at least two centimeters between the arms at one or more evaluation points7.

QoL was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Breast plus Arm Morbidity questionnaire (FACT B+4) (version 4.0), which has been translated into Portuguese and subjected to validation and reproducibility analysis in Portuguese (Brazil)8,9. After authorization of the FACIT System, the version of the questionnaire was provided for use in the present research. Authorization was also requested from the authors responsible for validation and reproducibility of the instrument in the Portuguese language (Brazil).

The FACT B+4 is composed of 40 questions distributed in six areas: physical well-being (seven items); social/family well-being (seven items); emotional well-being (six items); functional well-being (seven items) and additional concerns (additional concerns with breast cancer and additional concerns with the arm) (13 items). The instrument has questions related to the last seven days prior to the interview and presents a Likert-type scale with responses varying from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much)8.

A database was prepared in an electronic spreadsheet and was validated through double typing. The SPSS statistical program (version 17.0) was used for analyses. Sociodemographic, clinical and therapeutic variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

QoL was analyzed according to the guidelines of the FACT B + 4, provided by the FACIT System. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the scores of each domain and the score for the FACT B Total, using measures of position, i.e. mean, variance, and minimum and maximum values. It is noteworthy that the Guidelines do not determine a cutoff point for scores; high levels of responses are indicated by high scores, which determines a better QoL.

In the description of QoL results, the mean scores of each domain and of the FACT B Total are compared to the maximum possible values. Thus, the closer to the maximum allowable score, the better is the QoL.

The study was evaluated and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Alfenas (UNIFAL-MG) under Protocol: 208/2011. Informed Consent Forms (ICF) were signed by patients prior to the data collection and a copy was kept with them.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In the sample of 25 women, the age groups from 40 to 49 years and from 50 to 59 years predominated, both with the same frequency: 7 (28%). As for social characteristics, 19 (76%) women reported having a partner, 16 (64%) reported having active sexual life, 21 (84%) had children, and 20 (80%) declared to be Catholic.

A low level of education was the case of 11 (44%) women who had incomplete primary education. This indicates the need to establish a communication strategy that makes connections with the patient's limitations/strengths in order to facilitate self-care.

We observed that the sample had a sociodemographic profile typical of women with breast cancer and users of the Unified Health System (SUS) of the region where the study was carried out. The staging of the cancer shows that screening has been carried out with a lower frequency in the municipality.

As for surgery, all patients had undergone the procedure less than one year ago and 13 (52%) had operated the left breast. Regarding the most frequent surgical procedures, 11 (44%) patients had undergone conservative surgery and sentinel node biopsy and 10 (40%) modified radical mastectomy and lymphadenectomy.

In the arm circumference evaluation, 6 (24%) patient presented lymphedema. This morbidity is related to the developmental impairment of some actions: sports; home/work activities and activities that would increase the general knowledge10.

As to the histological grade of the tumor, grade II was predominant in 17 (68%) women. As for staging, 4 (16%) women presented stage I; 11 (44%) stage II; 4 (16%) stage III; and 6 (24%) presented no information regarding this variable. Still, 10 (40%) women had axillary lymphatic involvement.

Regarding the treatment, it was verified that in the case of 23 (92%) women, eight CT cycles were prescribed, and 6 (24%) women had gone through the third cycle.

The symptomatology of CT-related adverse events may present degrees of intensity that vary according to the health-disease process and the subjectivity of the patients. The triggering of these events is a problem that can be contextualized as a factor with a negative impact on the women's QoL.

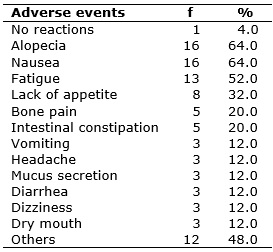

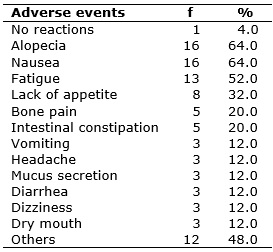

Regarding the CT-related adverse events, there was more than one response per interviewee. The patients cited alopecia, nausea and fatigue more frequently, mentioned by 16 (64%), 16 (64%) and 13 (52%) patients, respectively, as shown in Table 1. Only one patient denied feeling any symptom triggered by this therapy.

TABLE 1:

Adverse events of CT among patients in the countryside of southern Minas

Gerais, 2012. (N = 25)

Note: More than one response was given by each interviewee.

Other adverse events were reported: 2 (8%) patients reported numbness; 2 (8%) bad taste/bitter mouth; 1 (4%) burning in the nasal cavity; 1 (4%) burning at bladder and intestinal elimination; 1 (4%) face flushing and redness; 1 (4%) decreased body resistance; 1 (4%) weight gain; 1 (4%) edema throughout the body; 1 (4%) tremors; and 1 (4%) nasal congestion.

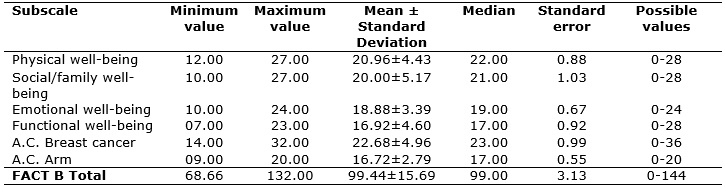

In the perspective that involves the aspects of the disease and of the therapeutics, in relation to the QoL assessment, patients presented, in general, good results in each domain and in the FACT B Total, as shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2:

Descriptive analysis of the responses to the subscales of the FACT B + 4

and of the FACT B Total. Countryside of southern Minas Gerais, 2012. (N =

25)

Note: A.C. Breast cancer = additional concerns with breast cancer; A.C. Arm

= additional concerns with the arm.

However, it is important to note the need to recognize the domains that had the lower and higher scores, for this knowledge is intertwined with the interpretations that health professionals can organize in order to determine the care. In the sample studied, the lowest mean scores were obtained in the additional concerns with breast cancer (22.68 ± 4.96/36) and functional well-being (16.92 ± 4.60/28), as seen in Table 2. On the other hand, the best mean scores were obtained in the domains additional concerns with the arm (16.72 ± 2.79/20) and emotional well-being (18.88 ± 3.39/24).

A study used the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-BR23 questionnaires to investigate the QoL of 39 women with breast cancer undergoing CT. In the first instrument, there was indication of a good QoL according to the scores of cognitive, social, and physical functions and role performance. However, a possible emotional fragility was indicated by the score in the emotional aspect11.

Still, the same authors found through EORTC QLQ-BR23 good results in the aspects of body image and future perspective. However, low scores were observed in sexual function and satisfaction, which explained an interference of the disease in these issues11.

Although overall good QoL results were found among the women investigated in the present study, it is relevant to discuss how each questioning was delineated in the domain that obtained the lowest score: Additional concerns with breast cancer. The objective is to understand the concerns regarding breast cancer, in order to favor a better identification of the patient' needs under CT and, consequently, allow the achievement of a better health care planning.

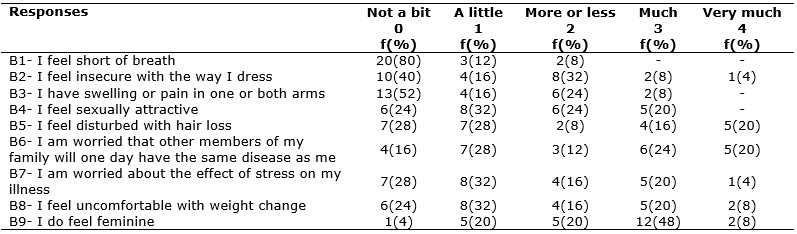

In the context of the domain additional concerns with breast cancer, it was noticed that the questions B2, B4, B5, B8, B9 allude to body image before the therapy, and these are factors that may influence women's QoL, as shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3:

Responses in the domain additional concerns with breast cancer. Countryside

of Minas Gerais, 2012. (N = 25)

The body changes imposed by breast cancer are related to the way the patient feels and perceives herself12. The therapeutic processes of mastectomy and CT may imply a breakdown in self-perception of sexual attractiveness of the female body. In the item I feel sexually attractive, only 5 (20%) participants opted for the answer very much, as shown in Table 3.

The shame related to mastectomy before society involves the meanings of mutilation of an organ interconnected with beauty, sensuality and femininity13. A research with a group of 90 women with breast cancer and another control group of 77 women without the disease showed that breast surgery and CT negatively affect the perception of the female self-image, with an unfavorable effect on the emotional and social aspects of women14.

In this context, the extirpation of the breast entails embarrassment for women to get undressed to partners, a decrease in nipple sensitivity and of the desire for sexual practice13. Still, in the experience of undergoing CT, unease acts as a triggering factor for the decrease in the exercise of sexuality15. Adverse events such as alopecia and weight changes that lead to changes in body aesthetics may be also a contributing factor for the women start feeling less sexually attractive.

The predominant age groups in the sample coincide with the climacteric period of the women's life cycle. The experience of this physiological process triggers changes with repercussions in different areas, including discomfort with the body modifications16. There was therefore a possibility of the interviewees having experienced characteristics of physiological changes peculiar of this period of life, which imply the imaginary of their being sexually attractive.

In terms of body changes, alopecia represented different degrees of discomfort among the interviewees, and only 7 (28%) said to feel not a bit uncomfortable, as shown in Table 3.

Alopecia is a characteristic that lead to the identification of a diagnosis of a disease stigmatized as lethal and becomes an obstacle to social relationships17. In this sense, hair loss brings anguish and social isolation to women, as they fear the curiosity or feelings of pity on the part of other individuals18.

Intrinsic to the contexts of CT-related adverse events, weight changes are evident in the discourses of women with breast cancer undergoing CT. In the investigated sample, 19 (76%) women showed some degree of discomfort with the weight changes, as shown in Table 3.

In the approach of chemotherapy, it is known that weight loss is probably related to gastrointestinal symptoms that cause difficulty to eat. On the other hand, there is weight gain associated with changes in taste and increased appetite19.

In the item I feel insecure with the way I dress, 10 (40%) women responded not a bit and 4 (16%) a little insecure. And in the item I do feel feminine, it was seen that 12 (48%) responded much and 2 (8%) answered very much, as shown in Table 3.

Accepting a new body image is a process that must be experienced by the women, their families and the surrounding environment. The naturalness in the way neighbors see these women ends up being promoting a welcoming feeling and a reduction of embarrassing feelings20.

It is worth mentioning that good results for emotional well-being and social/family well-being were evident in the sample investigated. In view of this, we suggest that these domains influence the preservation of ego in the way of dressing and feeling feminine. Researchers also recognize that family support is a positive factor and favors the search for life and assists in the coping with the course of the diagnosis and treatment 21.

With respect to the surgical process, it is necessary to emphasize the patients' arm as a determining limb used in daily activities22. In this sense, there is concern about the development of lymphedema, which can cause physical, emotional and social damage to women22.

As for the presence of swelling or pain in one or both arms, there was a low percentage of women who claimed to have a high degree of this morbidity, and 2 (8%) opted for the response a lot, as shown in Table 3. We understand that, although the majority - 13 (52%) women - did not present this complaint at all, awareness about self-care with this body part should be reinforced by the health professionals in order to avoid further decrease in QoL.

In the question I am concerned that other members of my family may one day have the same disease as me , 4 (16%) stated not a bit, according to Table 3.

In a study that sought to know the experience of families in the face of the discovery of cancer in one of their members, it was observed the projection of the diagnosis of cancer as a possible repetition of previous losses of relatives caused by this disease. Moreover, the study found that the meanings attributed to cancer and the way they are socially and culturally viewed can interfere with the way the patient and the family receive, interpret, and project the news about the disease23.

We suggest that women who have concerns with their relatives about the possibility of diagnosis of neoplasia make reflections about these explicit evidences in social circles, mainly valuing them. However, the prevention of this disease should involve care with other risk factors that are also associated with the occurrence of the breast cancer, such as early menarche, nulliparity, late menopause, diet, obesity, urban housing, absence of sexually active life and others24.

Living with the treatment of neoplasia requires a reversal of time and dedication: the time previously directed to leisure, family and work needs now to be allocated to other things12. In this sense, there is a risk of frustration in the management of time, since health care starts to demand time more intensely12.

In this perspective, it is worth mentioning the need to include in the care planning of cancer patients the structuring of means favorable to coping with the whole disease process. When asked about the effects of stress on the disease, 18 (72%) women reported having some degree of concern, as shown in Table 3.

Social support has proved to be an important factor for physical and emotional well-being of cancer patients25. In the present study, 21 (84%) women had children, and this suggests a favorable aspect for better coping with the obstacles posed by the new life perspective imposed by cancer.

Good results were obtained in the item I feel short of breath, because no patient chose the answers much or very much, according to Table 3.

In general, fear, nervousness and concern become present in the daily lives of people who come to experience situations that trigger the idea of danger to health26. Thus, it is essential to establish an interactive support network, in which family, religious and professional entities are included, in the search for humanized care26. In this context, nurses assume a prominent role in the diagnosis, treatment and coping with the disease, mainly through the implementation of the systematization of nursing care (SNC), whose strategies aim at embracement, qualified listening and shared consultations aimed at reducing the stressors coming from the disease process20.

CONCLUSION

An overall satisfactory result was found in the QoL assessment of the interviewees. The domains Additional concerns with the arm and Emotional well-being represented the ones with the best mean scores. On the other hand, the lower mean score was found in the domain Additional concerns with breast cancer.

A reflection on the way the factors in the domain Additional concerns with breast cancer were expressed by the women indicated the need to allude, in the care planning, to actions directed to a better coping with body image modifications, and with the effect of the stress caused by the disease and by the possibility of another members of the family being affected by cancer.

The role of nurses is fundamental to develop strategies to enable women under chemotherapy to reach a satisfactory and constant QoL throughout the disease process. Thus, based on the structuring of SNC actions, highlight must be given to health education, support groups and a holistic approach to patients.

Cross-sectional studies have limitations because this design makes it impossible to assess the QoL throughout the entire chemotherapy course. Therefore, we suggest the development of further studies aiming to evaluate this construct of women with breast cancer in the period prior to the first chemotherapy session until the end of this treatment.

REFERENCES

1.The Whoqol Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995; 41(10):1403-9.

2.Frenzel AP, Pastore CA, González MC. The influence of body composition on quality of life of patients with breast cancer. Nutr. hosp. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2013 [cited in 2017 Oct 29]; 28(5): 1475-82. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24160203

3.Simeão SFAP, Landro ICR, Conti MHS, Gatti MAN, Delgallo WD, Vitta A. Quality of life of groups of women who suffer from breast cancer. Ciênc. saúde coletiva [Scielo-Scientific Electronic Library Online] 2013 [cited in 2017 Sep 10]; 18(3): 779-88. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232013000300024

4.Machado MX, Soares DA, Oliveira SB. Significados do câncer de mama para mulheres no contexto do tratamento quimioterápico. Physis: revista de saúde coletiva [Scielo-Scientific Electronic Library Online] 2017 [citado em 12 de out 2017]; 27(3): 433-51. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-73312017000300433&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt

5.Kamińska M, Ciszewski T, Kukiełka-Budny B, Kubiatowski T, Baczewska B, Makara-Studzińska M, et al. Life quality of women with breast cancer after mastectomy or breast conserving therapy treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. agric. environ. med. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2015 [cited in 2017 Oct 29]; 22(4): 724-30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26706986

6.Gomes NS, Silva SR. Women's quality of life after breast cancer surgery. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2016; 24(3):e7634.

7. Ministéiro da Saúde (Br). Controle do câncer de mama: documento consenso 2004. Rio

de Janeiro: Inca; 2004.

8.Michels FAS, Latorre MRDO, Maciel MS. Validity and reliability of the FACT-B+4 quality of life questionnaire specific for breast cancer and comparison of IBCSG, EORTC-BR23 and FACT-B+4 questionnaires. Cadernos de Saúde Coletiva. 2012; 20(3): 321-8.

9.Silva FA. Validação e reprodutibilidade de questionários de qualidade de vida específicos para câncer de mama [dissertação de mestrado]. São Paulo: Fundação Antônio Prudente; 2008.

10.Panobianco MS, Campacci N, Fangel LMV, Prado MAS, Almeida AM, Gozzo TO. Quality of life of women with lymphedema after surgery for breast câncer. Rev Rene [Biblioteca virtual em saúde] 2014 [cited in 2017 Oct 30]; 15(2): 206-13. Available from: http://bases.bireme.br/cgi-bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&src=google&base=BDENF&lang=p&nextAction=lnk&exprSearch=26475&indexSearch=ID

11.Bushatsky M, Silva RA, Lima MTC, Barros MBSC, Neto JEVB, Ramos YTM. Qualidade de vida em mulheres com câncer de mama em tratamento quimioterápico. Ciênc. cuid. saúde. 2017; 16(3).

12.Milagres MAS, Mafra SCT, Silva EP. Repercussões do câncer sobre o cotidiano da mulher no núcleo familiar. Ciênc. cuid. saúde. 2016; 15(4):738-45.

13.Rocha JFD, Cruz PKR, Vieira MA, Costa FM, Lima CA. Mastectomy: scars in female sexuality. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line 2016 [cited in 2017 Oct 15]; 10(5): 4255-63. Available from: http://pesquisa.bvs.br/brasil/resource/pt/bde-29999

14. Prates ACL, Freitas-Junior R, Prates MFO, Veloso MF, Barros NM. Influence of body image in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Rev. bras. ginecol. obstet. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2017 [cited in 2017 Oct 29]; 39(4): 175-83. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28359110

15.Ferreira SMA, Panobianco MS, Gozzo TO, Almeida AM. A sexualidade da mulher com câncer de mama: análise da produção científica de enfermagem. Texto & contexto enferm. [Scielo-Scientific Electronic Library Online] 2013 [citado em 10 set 2017]; 22(3): 835-42. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v22n3/v22n3a33.pdf

16.Fonseca TC, Giron MN, Berardinelli LMM, Penna LHG. Quality of life on climacteric nursing professional. Rev Rene. 2014; 15(2): 214-23.

17.Jayde V, Boughton M. Blomfield P. The experience of chemotherapy-induced alopecia for Australian women with ovarian câncer. Eur. j. cancer care. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2013 [cited in 2017 Oct 29]; 22(4): 503-12.

18.Reis APA, Gradim CVC. Alopecia in breast câncer. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line. 2018; 12(2): 447-55.

19.Vargens OMC, Brasil TA, Cardozo IR, Silva CM. Young women with breast cancer: fighting cancer and the mirror. Enfermagem Obstétrica. 2017; 4: e109:1-7.

20.Batista KA, Merces MC, Santana AIC, Pinheiro SL, Lua I, Oliveira DS. Feelings of women with breast cancer after mastectomy. J Nurs UFPE on line. 2017 [cited in 2017 Oct 12];11(7): 2788-94. Available from: https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/viewFile/23454/19167

21.Sant'Ana RSE, Santos ADSS, Bity ABS, Matos RM. Interferences of cancer treatments in women's sexual performance. Rev. eletrônica enferm. 2013; 15(2):471-8.

22.Assis MR, Marx AG, Magna LA, Ferrigno ISV. Late morbidity in upper limb function and quality of life in women after breast cancer surgery. Braz. j. phys. ther. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2013 [cited in 2017 Oct 29]; 17(3): 236-43. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23966141

23.Karkow MC, Girardon-Perlini NMO, Stamm B, Camponogara S, Terra MG, Viero V. Experience of families facing the revelation of the cancer diagnosis in one of its integrants. REME rev. min. enferm. [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2015 [cited in 2017 Oct 28]; 19(3): 741-6. Available from: http://bases.bireme.br/cgi-bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&src=google&base=BDENF&lang=p&nextAction=lnk&exprSearch=28190&indexSearch=ID

24.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Falando sobre câncer de mama. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Inca; 2002.

25.Ng CG, Mohamed S, See MH, Harun F, Dahlui M, Sulaiman AH, et al. Anxiety, depression, perceived social support and quality of life in Malaysian breast cancer patients: a 1-year prospective study. Health qual. life outocomes [US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health] 2015 [cited in 2017 Oct 28]; 13(205): 1-9. Available from: https://uitm.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/anxiety-depression-perceived-social-support-and-quality-of-life-i

26.Nascimento KTS, Fonsêca LCT, Andrade SSC, Leite KNS, Costa TF, Oliveira SHS. Feelings and sources of emotional support for women in pre-operative mastectomy in a teaching hospital. Rev. enferm. UERJ. 2015; 23(1):108-14.