RESEARCH ARTICLES

Experience of mothers in neonatal intensive care unit

Laurita da Silva CartaxoI; Jamili Anbar TorquatoII; Glenda AgraIII; Maria Andréa FernandesIV;

Indiara Carvalho dos Santos PlatelV; Maria Eliane Moreira FreireVI

ABSTRACT: This study aimed at assessing the experience of mothers of premature newborns staying in neonatal intensive care unit. Descriptive, quantitative and qualitative study with 20 mothers experiencing the hospitalization of their premature newborns. Data were collected from November to December, 2010, by means of interview technique, analyzed in light of the collective subject discourse. Results showed that mothering premature newborns is a very difficult experience, causing a stressful and fragile emotional state to the mother, enhanced by her fear of losing her child, despite acknowledging the need for treatment. Therefore, establishment of bond between mother and child with baby holding are essential to enhance affection, care, and acceptance. Mothers of premature babies become increasingly more confident and able to overcome difficulties and fear when they realize they can provide care for the child, even in hospital.

Keywords: Life experience; mothers; premature babies; neonatal intensive care units.

INTRODUCTION

A premature child proves to be a stressful experience to the family, having to cope with an unpredictable anxiety-generating event. On account of the baby’s organic instability and its resulting need for specialized medical care at Intensive Care Units (ICU) the mother experiences the separation from her premature baby, unsure of its clinical evolution and survival. The family starts to build upon a distorted ideal image of the newborn, a fact that adds difficulties to the frame, for that image shall always differ from the premature baby’s real image. Therefore, the family reorganizes their imaginary frame so that it fits the image of a fragile and small newborn2.

Hospitalization levels at ICUs are regarded as high, in view of the abnormal birth conditions, as that of prematurity, low birth weight, anoxia, malformation, and other clinic conditions that predispose newborns to specialized treatment to ensure their survival. This condition causes parents high impact, suffering, high anxiety levels, depression, hostility, sadness, melancholy, psychosocial problems, with special emphasis on mothers, in addition to a wide spectrum of expectations as to the child’s treatment3,4.

At the ICU, the newborn undergoes a number of procedures and interventions, such as aspiration, intubation, catheterization, vein puncture, among others, which permeates the entire treatment during hospitalization. Thus, the mother experiences moments of pain and strong conflicts, in face of her expectations about a healthy baby while pregnant. The birth of an unhealthy baby undoes that dream and brings about disappointment, feelings of failure, guilt, and fear of loss5.

A number of further problems to be faced by the mother are added to that condition, among which fear of the disease, of the unknown, of high-tech and machine-equipped hospital environment, and the realization of the child’s condition, which, in most cases, culminates in emotional crisis6.

As for the child’s hospitalization, transformations in neonatal assistance have been observed, as for instance, the insertion of the family in that context, with the mother’s company during her child’s hospitalization, a right consolidated in the Child and Adolescent’s Statute7.

Granted that mothers of hospitalized newborns at ICU require special care, aspects of their emotional and social frames must be assessed as well as support must be available to the exercise of their maternal role, in view of the need to enhance mother-child bond at that moment.

A study conducted in that area portrays different responses by mothers to their children’s hospitalization at ICU, where reception and communication among professionals might not take place as expected, as well as mothers’ emotional vulnerability, in special, might be disregarded. Moreover, in the art of caring, communication is essential and works as a therapy option8.

In that context, the ICU team must develop an emphatic relation to mothers, in order to assist both those special beings and their families in coping with disease and suffering, so that they can infer positive meaning out of that experience, whenever possible9.

In that perspective, to understand how mothers of premature newborns hospitalized at ICUs experience that condition, this study aimed at assessing the experience of mothers of premature newborns hospitalized in that unit.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Separation from a newborn as a result of its hospitalization brings about sadness, fear, and stress to parents; they feel sensitive and unsure about their child’s life, experience mixed feelings such as guilt, take on responsibility for their child’s suffering and, at the same time, show hope and acceptance10.

The hospitalization of a premature newborn at an ICU turns out to be a critical situation to the entire family, especially to the mother. That is a strange and frightening environment, in addition to the fact that real baby is different from the imagined one, and the guilt feelings about the child’s problems act as inhibiting factors to spontaneous contact between parents and babies11.

To the mother, staying at the ICU with her child, while she should be in charge of caregiving at home, brings about loss to the maternal role, and problems with identifying herself as a mother, and many a time, with identifying her baby, because there is a team in charge of the caregiving that should be on her12.

Maternal feelings in relation to a premature baby can be attenuated or aggravated according to the opportunities that mother is given to somehow participate in her child’s caregiving. The usual deprivation of mother’s childcare during hospitalization mixes up expectations about her role during that time13.

Lack of opportunities for affective interaction between mother and her hospitalized child may cause a loss to their bond and generate disorders in their future relationship. Evidence has been found in scholarly studies that affective bonds develop since intra-uterine life, and that early contact in post-natal life is essential14.

Thus, planning interventions is decisive to stimulate parent-child bonds, as well as to favor their adaptation to neonatal units, as for instance, the parents’ free access and stay at the neonatal unit, incentive to physical contact and early care, implantation and structuring of groups, parental and family support network with the cooperation of multi professional team, as well as shared decision-making on the assistance to the premature newborn15.

To make those actions come to a term, professionals must develop affective interaction, understand parents’ experience at that stage in life, be able to open up legitimate room for the expression of their feelings, and offer concrete and facilitating elements to provoke transformations, to overcome barriers to their transit where their child is16.

METHODOLOGY

This is a descriptive piece of research with quantitative and qualitative approach. In the descriptive study, facts are observed, registered, analyzed, classified, and interpreted, with no interference by the researcher17.

The study was conducted from November to December, 2010, with the participation of 20 mothers of premature newborns hospitalized at ICU of a state-owned maternity, in the municipality of João Pessoa-PB, Brazil. Participants’ selection was based on accessibility, according to inclusion criterion established, as for instance, being of age and staying with the child at the ICU during data collection. Data was obtained on the basis of interview techniques conducted in a maternity hospital room, on a semi-structured script, including questions related to the objectives formulated.

Social and demographic data as well as obstetric background were submitted to statistics analysis after calculation of absolute and percentage frequency.

Data were organized and analyzed on the basis of the collective subjective discourse (CSD). That technique sheds light onto the set of representations that can confirm an imaginary datum18. Analysis procedures were started with comprehensive readings of the material until primary ideas of the analysis plan could be identified. Key expressions were then selected out of each discourse piece to allow for the identification of the central idea in each one of the pieces, and thus representing the contents synthesis of those expressions comprehending the collective subject discourse. This research met the requirements provided for in Resolution # 196/96, by the National Committee for Research Ethics (CONEP). Data were collected after publication of a favorable opinion by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Faculdade Santa Emília de Rodat (051/2010) upon participants’ approval and signing of the Informed Consent, which ensured anonymity, exclusive use of data in this study, and the right to withdraw consent in their discretion.

RESULTS ND DISCUSSION

Subjects’ profile

Out of the 20 (100%) women having recently given birth participating in the study, 13 (65%) aged 18 to 29 years old and 7 (35%), aged 30 to 39 years old. As for their marital status, 9 (45%) interviewees were married, 6 (30%) had stable union, and 5 (25%) stated they were single. As for schooling, 11 (55%) mothers had attended high school; 7 (35%) had elementary education; 1 (5%) had college education and 1 (5%) had not had any formal education.

As for the obstetric background of those participants, 9 (45%) were found to be primiparous, whereas 11 (55%) were multiparous. During pregnancy, 11 (55%) of those mothers had four to six pre-natal medical visits; 4 (20%) had from one to three visits; 3 (15%) had over seven visits within that period, and 2 (10%) had no such information on their record. As for the mode of delivery, records showed that 12 (60%) mothers had C-section, and that eight (40%) had normal birth. On gestational age, 10 (50%) of the mothers had their newborns between 24-30 weeks and 30-36 weeks, the remaining 10 (50%) correspond to the total of pre-term pregnancies.

Collective subject discourse (CSD)

The elaboration of this part of the study disclosed questioning and synthesis-discourse, which gave rise to their respective central ideas, spread out in figures.

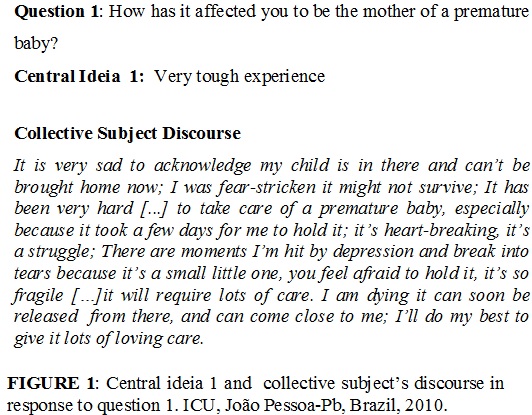

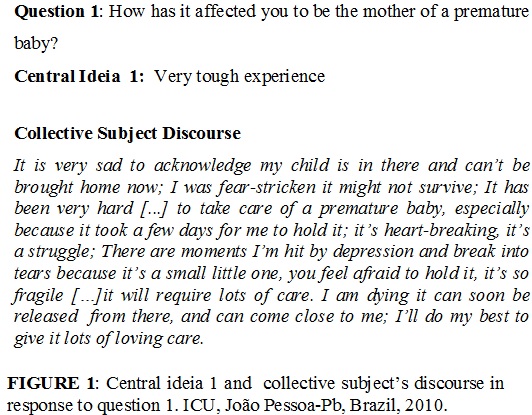

In face of the question, the CSD was expressed in central idea 1; it discloses feelings and wishes by the participants, endowed with sadness, suffering, and fear, considering their inexperience and failure to give maternal care in view of fragile and sensitive condition brought about by prematurity. See Figure 1.

A premature birth cause mothers a shock response resulting from unexpected birth, and more frequently, from the fragile look of the baby. That perception makes family and mother, in special, unsure19.

Experiencing a child’s hospitalization at ICU, mothers go into a new dimension of reality, usually struck by hard moments in sadness, pain, and hopelessness20.

That experience throws mothers off balance emotionally, some of them unable or lacking the opportunity to voice their suffering and keeping quiet and lonely about it. That phase can last few days or can stretch out for months in a row, given their expectation that might reach an end12.

Thus, understanding mothers’ feelings at that moment can prove to be relevant support to planning welcome actions by the multi professional team at the ICU, and to help out coping.

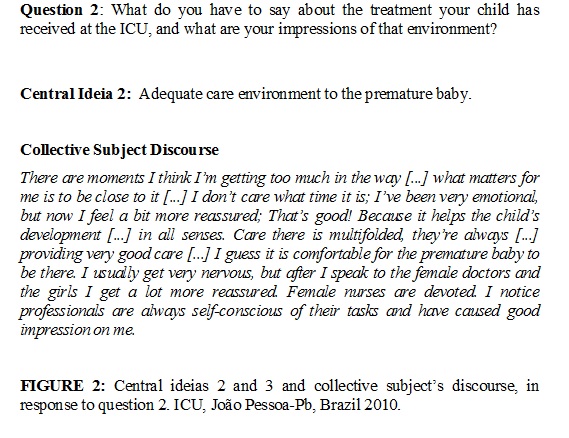

In view of question 2, CSD disclosed central idea 1, which expresses mothers’ opinion on their child’s treatment at ICU. Although they find technologies used in that environment frightening and stressful, they found treatment necessary in view of improvement expectations. See Figure 2.

As for technological resources used in the premature newborns’ treatment, the interviewees’ discourse expressed affliction caused by the realization of their newborns’ condition: on machines, catheters, incubators, phototherapy, infusion plump, nasogastric tube, umbilical catheter, nasal catheter, wrist oxymeter, among other therapeutic resources necessary to preserving their lives and recovering their health12.

The frequent manipulation of the newborn as well as the mechanical and technical conduction of the ICU routine procedures, show little regard towards comfort, sleep, and rest needs of that being in development. In addition to the intensive care routine the premature newborn undergoes, technology prevails over humanized care2.

Mothers’ testimonies show in between the lines there is symbolic fracture between giving birth and not holding the child, as a result of the separation imposed by a wide range of equipment and therapeutic processes the premature newborns undergo; such impressions were equally identified in research on mothers’ representations of premature child’s hospitalization14.

In this respect, the CSD unveils how hard it is for a mother to see her child on machines and exposed to painful procedures, a situation in which they feel powerless and helpless; they must therefore, receive emotional support by both the professionals involved and their close family members.

Central idea 2 in question 2, emerging out of CSD analysis, discloses that mothers show they understand it is an adequate care environment to premature child and that they feel confident and reassured, despite moments of fear and tension, for they count on attention from the ICU professionals, who alleviate their anxiety and affliction. See Figure 2.

Such discourses evince ambivalence in signifying the ICU, enhanced both with feelings of pain and suffering for the child’s hospitalization, on the one hand, and with feelings of reassurance about the treatment they are receiving at that unit.

It is worthy highlighting that the process of mother’s adaptation to child’s hospitalization seems to be influenced by external factors on the social, cultural, and family fronts. Different life histories and experience mirror different feelings and attitudes among people13.

The type of assistance provided by the team can lead mothers to express their feelings, affliction, fear, and anxiety; it can attenuate family suffering in relation to the child and enhance mother-baby bond5.

Thus, mother and family must be included in the ICU environment. An effective communication channel among professionals and parents must be set up so that experience can be less painful, and affective bonds and maternal trust can become allies in the process of assisting the premature baby.

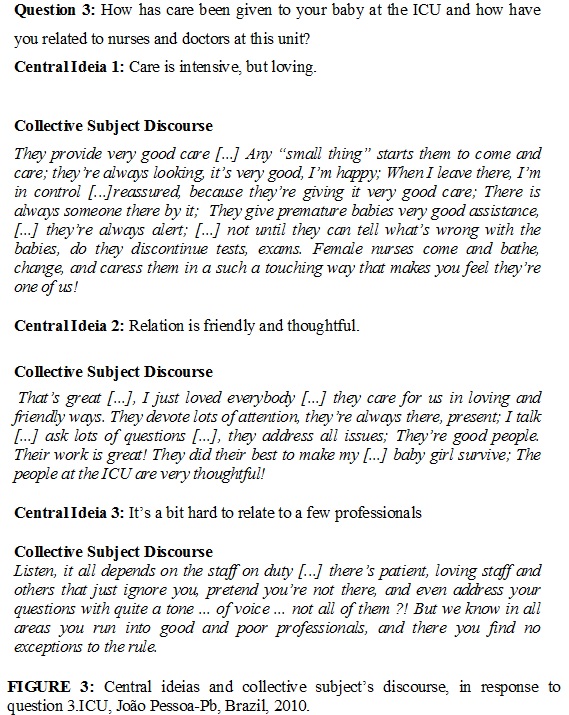

In question 3, the emerging central idea 1out of CSD, unveils that mothers value intensive care given to their children and that they highlight the team showed devotion, affection, and love, in addition to competence.

The truth of the matter is assistance focus at the ICU lies on the premature newborn4. To promote humanized mother-child centered assistance, the nursing team must value the potential of those women experiencing motherhood and must reflect on their anxiety and helplessness condition caused by the intensive treatment their premature child is undergoing. This way assistance can meet the need of the real mother being10.

The nurse must acknowledge the mother as an active participant in the care given to the child, must allow her free access to her child, training her to take care of the baby and giving her freedom to express her vision of the world-life. The nurse must still be sensitive to acknowledge the mother’s moments of affliction, in order to motivate her with an optimist regard towards a better understanding of her experience. It is meeting real maternal needs that team and mother favor inter subjectivity and sharing in order to attain understanding of child care.

Still on question 3, CSD on central idea 2 essentially shows mothers’ satisfaction with the relation established with the professional team at the ICU. See Figure 3.

Man’s living is characterized by constantly being with others and with things that take part in the world around. Thus, relating to others is part of human existence, and it makes it possible for the being to be able to touch and to be touched by others21.

Difficulties in the process of communication between family and the team have been disclosed in studies conducted with mothers accompanying their premature children15. However, it is evident in the testimonies of those participating in this study that empathic interaction and conviviality with the professionals can enhance coping strategies, helping mothers to overcome fear. Harmonious and supportive conviviality stimulates bond in such a way that mothers feel relatively at home in the child’s hospitalization environment. On the other hand, CSD in central idea 3, related to question 3, signals to dissatisfaction on the part of some participants with a few staff members. In between the lines of their testimonies, one can read a few professionals in the unit have little regard for the mothers’ presence, giving exclusive assistance to the child. Such assistance means to work with their parents too, because they are immediate representatives of the baby, the mothers in special, for the child stands for an extension of her being.

Studies along that line of attention disclose that professionals must be trained to cope with everyday situations, receiving psychological assistance and learning to manage feelings experienced in assistance practice20. Team encouragement and enhancement of professionals are essential because whenever they feel respected and motivated they can establish more meaningful and healthier interpersonal relations with patients, family, and multi professional team.

It comes in time to think over the way we conduct our assistance in order to contemplate not only practical and technical activities but also to ensure a warm and humanized welcome to both mother and newborn, integrating a bio psychosocial set.

CONCLUSION

Discourse analysis of mothers of premature newborns hospitalized at ICU allowed for the understanding the phenomenon under investigation. They disclosed that environment intensifies emotions and causes pain, and is directly related to factors and influences that affect mother-child relation, breaking bond formation between them.

In the mothers’ ambivalent discourses, neonatal ICU paradoxical aspects are highlighted, as life and death, fear, helplessness, pain, suffering, separation, and death risk to the newborn, in simultaneous opposition to life-saving values. Thus, the ICU was portrayed as a frightening, yet necessary environment. Participating mothers prompted expectations for improvement of the child’s condition, despite hospitalization, prematurity, and conflicts generated by the process experienced.

By expressing a good relation with the health team at the ICU, mothers maintained a trust-based relation with those professionals, reporting self-assurance and confidence about caregiving to their children, which attenuated their anxiety.

Understanding the feelings of those mothers implies restoring their own moral value while beings in the world, as their needs are met on the basis of affection and assurance about their hospitalized child.

Those results call for a new regard over neonatal assistance, in which not just the psycho biological needs of the premature newborn are met, but specifically, the emotional and socio economical dimensions of the mothers in fragile conditions on account of their children’s premature condition.

REFERENCES

1. Araújo BBM. Vivenciando a internação do filho prematuro na UTIN: (re)conhecendo as perspectivas maternas diante das demandas neonatais [dissertação de mestrado]. [Internet] Rio de Janeiro: Faculdade de Enfermagem UERJ, 2007. [citado em 07 abr 2014]. Available at: http: //www.dominiopublico.gov.br/pesquisa/DetalheObraForm.do?select_action=&co_obra=89337

2. Araújo BBM, Rodrigues BMRD. O alojamento de mães de recém-nascidos prematuros: uma contribuição para a ação da enfermagem. Esc Anna Nery. [Internet]. 2010. [citado em 07 mar 2014]; 14: 284-92. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ean/v14n2/10.pdf

3. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas. Atenção à saúde do recém-nascido: guia para profissionais de saúde. 2011. [citado em 20 mar 2014]. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/atencao_recem_nascido_%20guia_profissionais_saude_v4.pdf

4. Martinez JG, Fonseca LMM, Scochi CGS. Participação das mães/pais no cuidado ao filho prematuro em unidade neonatal: significados atribuídos pela equipe de saúde. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. [Internet]. 2007. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 15: 239-46. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v15n2/pt_v15n2a08.pdf

5. Baldissarella L, Dell’Aglio DD. No limite entre a vida e a morte: um estudo de caso sobre a relação pais/bebê em uma UTI neonatal.Estilos da clínica. [Internet]. 2009. [citado em 07 set 2014]; 14(26):68-89. Available at: http://www.revistasusp.sibi.usp.br/pdf/estic/v14n26/05.pdf

6. Gorgulho FR, Pacheco STA. Amamentação de prematuros em uma unidade neonatal: vivência materna. Esc Anna Nery. [Internet]. 2008. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 12:19-24. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ean/v12n1/v12n1a03.pdf

7. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. 2008. [citado em 10 mar 2014]. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/estatuto_crianca_adolescente_3ed.pdf

8. Leopardi MT. Teoria e método em assistência de enfermagem. Florianópolis (SC): Soldasoft; 2006.

9. Coelho LP, Rodrigues BMRD. O cuidar da criança na perspectiva da bioética. Rev enferm UERJ. [Internet]. 2009; 17: 188-93. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; Available at: http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v17n2/v17n2a08.pdf.

10. Moreira JO. A ruptura do continuar a ser: o trauma do nascimento. Revista Mental.[Internet]. 2007. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 5(8): 91-106. Available at: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php

11. Araújo BBM, Rodrigues BMRD, Rodrigues EC. O diálogo entre a equipe de saúde e mães de bebês prematuros: uma análise freireana. Rev enferm UERJ. [Internet]. 2008; [citado em 10 mar 2014] 16:180-6. Available at: http://www.facenf.uerj.br/v16n2/v16n2a07.pdf

12. Ramalho MAM, Kochla KRA, Nascimento MEB, Peterlini O. A mãe vivenciando o risco de vida do recém-nascido prematuro na unidade de terapia intensiva neonatal. Rev Soc Bras Enferm Ped. [Internet]. 2010. [citado em 12 out 2014]; 10(1):7-14. Available at: http://www.sobep.org.br/revista/images/stories/pdf-revista/vol10-n1/v.10_n.1-art1.pesq-a-mae-vivenciando-o-risco-de-vida.pdf

13. Barradas AMCR, Ramos N. Parentalidade na relação com o recém nascido prematuro: vivências, necessidades e estratégias de intervenção. [dissertação de mestrado]. [Internet]. Portugal, Lisboa: Universidade Aberta de Portugal, 2008. [citado em 10 mar 2014]. Available at: http://repositorioaberto.uab.pt/handle/10400.2/735

14. Arivabene JC, Tyrrell MAR. Método mãe canguru: vivências maternas e contribuições para a enfermagem. Rev Lat-Am Enferm. [Internet]. 2010. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 18:130-6. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v18n2/pt_18.pdf

15. Gomes ALH, Quayle J, Neder M, Leone CR, Zugaib M. Mãe-bebê pré-termo: As especificidades de um vínculo e suas implicações para a intervenção multiprofissional. Rev Ginecol Obstet. [Internet]. 2007. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 8:205-8. Available at: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php

16. Oliveira BRG, Lopes TA, Vieira CS, Collet N. O processo de trabalho da equipe de enfermagem na UTI neonatal e o cuidar humanizado. Texto contexto enferm [Internet]. 2006. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 15(Esp):105-13. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tce/v15nspe/v15nspea12.pdf

17. Chizzotti A. Pesquisas em ciências humanas e sociais. São Paulo: Cortez; 2005.

18. Lefèvre F, Lefèvre ANC. O sujeito que fala. Interface – Comunic, Saude, Educ. [Internet]. 2006. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 10: 517-24. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/v10n20/17.pdf

19. Silva RV, Silva IAA. Vivência de mães de recém-nascidos prematuros no processo de lactação e amamentação. Esc Anna Nery. [Internet]. 2009. [citado em 20 mar 2014]; 13:108-15. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ean/v13n1/v13n1a15.pdf

20. Cruz DCS, Suman NS, Spíndola T. Os cuidados imediatos prestados ao recém-nascido e a promoção do vínculo mãe-bebê. Rev esc enferm USP. [Internet]. 2007. [citado em 10 mar 2014]; 41:690-7. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/reeusp/v41n4/20.pdf

21. Heidegger M. Ser e tempo. 5ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes; 1997.