RESEARCH ARTICLES

Maternal mortality from hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes: epidemiologic analysis over one decade

Deise Maria do Nascimento SousaI; Igor Cordeiro MendesII; Erison Tavares de OliveiraIII; Ana Carolina Maria de Araújo ChagasIV; Hellen Lívia Oliveira CatundaV; Mônica Oliveira Batista OriáVI

INurse. Master's Program of Graduate Studies in the Department of the Federal University of Ceará Nursing. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: deisemnascimento@yahoo.com.br

IIEnfermeiro. Master's Program of Graduate Studies in the Department of the Federal University of Ceará Nursing. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: igormendesufc@yahoo.com.br

IIINursing Student the Federal University of Ceará. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: erison_8@hotmail.com

IVEnfermeira. Master in Nursing from the Federal University of Ceará. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: aninhaaraujoc@hotmail.com

VEnfermeira. Master's Program of Graduate Studies in the Department of the Federal University of Ceará Nursing. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: hellen_enfermagem@yahoo.com.br

VIEnfermeira. Post-PhD in Nursing from the University of Virginia, United States. Associate Professor, University of Nursing Department Federal do Ceará. Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E-mail: oriaremon@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

This study identifies social and demographic profiles and analyzes Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) from hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes in Ceará, Brazil. Epidemiologic and documentary study. It was conducted on the Information System of Maternal Mortality database at the Secretary of Health of the state of Ceará, Brazil, and encompassed the years 2001 to 2010, with 356 records of maternal deaths. Most women who died from hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes aged between 20-34 years, had 1-7 years of formal education, were mulatto, single, and resided in the backlands of the state. Death occurred predominantly during pregnancy. MMR moved up from 2001 to 2010. Maternal mortality from hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes is a serious public health problem and the decrease of existing levels is required to improve health indicators.Keywords: Maternal mortality; pregnancy-induced hypertension; hemorrhage; epidemiology.

INTRODUCTION

Maternal mortality is a health problem that can be avoided in most cases by qualified health care services, and is considered a good indicator of health to verify the quality and conditions of life of the female population, the access to adequate obstetrical care and the public policies responsible for these actions1.

In 2006, in Brazil, the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), which is given by the expression that estimates the risk of death from pregnancy due to complications of pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, divided by the number of live births in the period, was 53 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. In addition, the corrected MMR was 74 per 100,000 live births, corresponding to 1,623 maternal deaths. It is noteworthy that the Northeast, North and Midwest had the highest MMR2.

In the year of 2008, the MMR was 58 deaths per 100,000 live births, which represents 1,800 deaths and the possibility of maternal death every 860 pregnancies. However, according to the Mortality Information System (MIS) of the Ministry of Health (MH), during the same year there were 1,691 maternal deaths1.

Given these considerations, it is relevant to verify the incidence of maternal mortality from direct obstetric causes in Ceará, more specifically hypertension and bleeding, which are the most prevalent in Brazil.

The objectives were to describe the sociodemographic profile of maternal death, as well as analyze epidemiologically the rate of maternal mortality by causes of hypertension and bleeding in the state of Ceará.

LITERATURE'S REVISION

In the state of Ceará, the MMR ranged from 93.3 / 100,000 live births in 1998 to 85.9 in 2002. It was also verified a lack of information of variables such as income, prenatal care and education in a high percentage of deaths3.

The main triggering causes of maternal death can be classified as direct obstetric, which are complications that result uniquely from pregnancy, indirect obstetric, resulting from pre-existing conditions, but aggravated by pregnancy, or not obstetric or unrelated, coming from other accidental or incidental causes that occurred during pregnancy, but unrelated to it3.

In the country, the predominant maternal deaths are from direct obstetric causes, excelling hypertensive diseases and hemorrhagic syndromes, and among the direct causes, the specific hypertension disease of pregnancy, eclampsia and preeclampsia, represented the first cause of maternal death year 2003 4.

There are two forms of hypertension which may complicate pregnancy: pre-existing hypertension (chronic) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (pre-eclampsia/eclampsia), which may occur alone or in association. The pre-eclampsia/eclampsia determines the largest number of perinatal deaths in Brazil, besides the increase in the number of newborns with sequels when survive the damage of cerebral hypoxia3.

It is worth mentioning that between 10-15% of pregnancies have bleeding, and that the most important hemorrhagic situations in pregnancy in the first half of pregnancy are abortion, ectopic pregnancy, benign gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (hydatidiform mole) and amniochorion detachment. In the second half of pregnancy, the most common are placenta previa, abruptio placentae, uterine rupture and vasa prior1,3.

The higher maternal age, lower education level, type of occupation, fewer prenatal consultations, lack of partner and health preconditions are considered risk factors for maternal mortality. However, maternal death from direct causes presents, nowadays, as another expression of the social question, relating to the socioeconomic conditions of women as well as access to education and qualified health services, which need to be solved in the context of social, health and education in the country5.

METHODOLOGY

This study presents epidemiological, descriptive, documentary and transverse lineation and quantitative approach. The study was conducted in the Coordination of Health Promotion and Protection (COPROM), more specifically in the Nucleus of Health Information and Analysis (NUIAS) of the Secretariat of Health of Ceará (SESA), place responsible for processing and storing data on the Mortality Information System (SIM).

This database is powered by completing the Death Certificate (DO). In addition to its legal function, death data are used to know the health status of the population and generate actions aimed at improvement. To do so, must be reliable and reflect reality. Mortality statistics are produced based on the DO issued by the doctor5. The population was represented by the cases of maternal death by hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes reported in the SIM between 2001 and 2010 and available in NUIAS, constituting 244 cases of maternal deaths due to hypertensive causes and 112 due to hemorrhagic causes. These causes were thus categorized according to the determination of the Maternal Mortality Committee to direct and indirect maternal deaths, according to the designation given in ICD-103.

Data collection was conducted in July 2012 through the state bank available in SESA. From this, the researchers selected the data needed to achieve the objectives of this research, being used records related to the DO, referring to maternal death due to hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes. In the data analysis were performed simple statistical calculations, with absolute and relative frequencies, as well as calculation of maternal mortality's ratio for specific causes in question. The study was submitted to the Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal do Ceará, being approved by protocol Nº 66/12.

RESULTS

It can be observed the demographic profile of the women who had mortality outcomes during pregnancy, childbirth or in the postpartum under the period of the study. All women who died due to hypertensive or bleeding causes were aged between 13 and 49 years, with the highest rates in the age group between 20-34 years, corresponding to 58.20% (n = 142) due to hypertensive diseases and 58.93% (n = 66) due to bleeding causes.

As for education, it was found that the highest proportion of women who died from hypertensive causes had 4-7 years of education (13.93%), and those who died of hemorrhagic causes had only 1-3 years of study.

About the race, it was noted higher prevalence of brown in the groups of hypertensive and hemorrhagic diseases, corresponding to 65.57% (n = 160) and 62.50% (n = 70), respectively. Regarding marital status, the highest prevalence was single, in both groups.

It can be observed significant differences between the place of residence of the woman and the place of occurrence of death in both groups of conditions studied in this research. Note that, in both groups of pathologies, more than 80% of women were living in the countryside of Ceará. However, it appears that many of these women who lived in the countryside died in the state capital.

This can be seen by comparing the variables place of occurrence and place of residence, it notes a rise in the number of women who died in the capital against those who actually lived in this county. In the group of hypertensive disease, 111 (45.49%) women died in the capital, while 48 (19.67%) lived in Fortaleza. Regarding hemorrhagic diseases, 31 (27.68%) women died in the capital, but only 12 (10.71%) lived truly in this city.

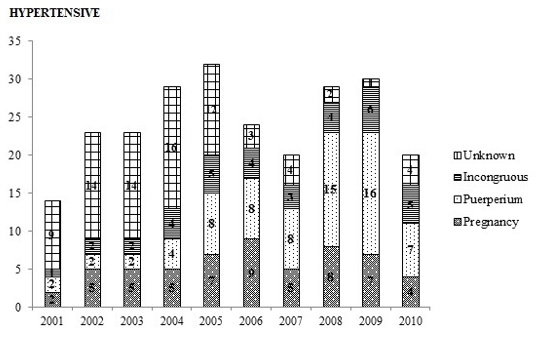

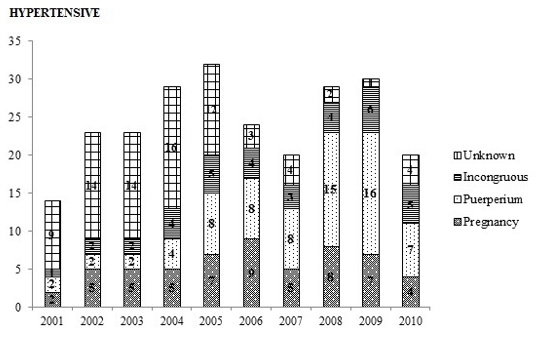

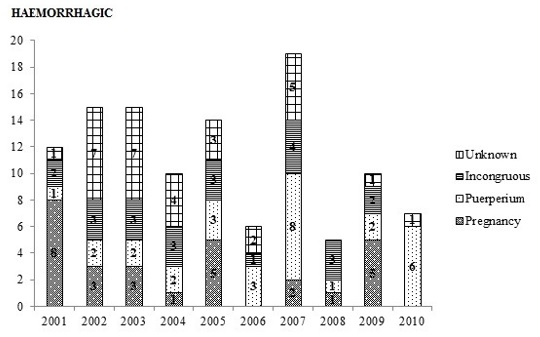

Regarding the time of maternal deaths from the causes outlined, the data were categorized by evaluating two existing questions on Death Certificates (DO) that refer to the period of occurrence of maternal death, divided into: death occurred in pregnancy / childbirth / miscarriage or postpartum. However, it has been verified that in many cases these data were inadequately filled, stating that the death had occurred in both pregnancy and puerperium, being considered, therefore, an incongruous information. Moreover, on several occasions, the record of this item was ignored, characterizing undercount. The data not notified, either mismatch or data dropped was approximately 48% for both cases.

Among duly recorded, prevailed maternal death during the postpartum period (55% for the hypertensive causes and 51.72% for hemorrhagic causes). Throughout the series, the year 2009 was the one with the most deaths during the postpartum period. But the death occurring during pregnancy was more prevalent between 2005 and 2009. The cases classified as incongruent were noticed in all the years and they obtained significant numbers, being the apex of registered cases in 2009. With regard to deaths from hemorrhagic causes, we realize that the number of ignored cases were those who had higher expression in the historical series from the questions presented. The deaths that occurred during pregnancy were the most frequent, followed by those that occurred in the postpartum period. The data showed inconsistency in the information provided were responsible for a significant number of cases, with a value close to those that occurred in the postpartum period, relative to Picture 1.

Regarding Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) due to hemorrhagic and hypertensive causes, it was observed that the one related to hypertensive diseases, showed higher numbers than the hemorrhagic ones, over the decade studied. The MMR by hypertension grew from 2001 to 2005, with considerable decline in the subsequent years, the largest and most significant of them, reported in 2007. When maternal mortality decreased from 22.89 to 14.95 deaths per live births, the lowest rate in the time series analyzed. In 2008 and 2009, the ratio was found to be increasing again and in 2010, it suffered a considerable decrease, with the ratio number similar to the one in 2007, which registered the lowest rate. The MMR by hemorrhagic causes, from 2001 to 2003 showed a steady increase, but with similar values in each of these years.

In 2004 and 2005, the rate for each year ranged between increases and decreases, until in 2007, showed a greater increase in relation to others. In the following years the MMR, continued oscillating, but in 2008 fell by nearly 75% compared to the previous year. In 2009 and 2010, it had a small increase and the ratio remained stable, as it has shown on Picture 2.

DISCUSSION

With regard to age, it was found that between 20 and 34 occurs the highest number of maternal deaths from hypertensive and hemorrhagic diseases, corroborating by study conducted in the state of Paraíba in which were analyzed 116 maternal deaths certificates of women living in the period 2000-2004. In this study, it was found that 84.4% of maternal deaths were due to direct obstetric causes and 59.7% were aged 20-34 years, i.e., in the reproductive age6. In another study in the period 2000-2009, it was found that the highest prevalence of maternal deaths in Brazil was in the age group 20-29 years (41.85%), followed by the group between 30 to 39 years7.

It can be seen that the main age-related to maternal deaths occurs in the age corresponding to the period of greatest fertility, where it is recommended that there is no risk to the woman. However, this fact may be reporting to a prenatal, childbirth and puerperium care of poor quality, where there isn't early diagnosis of these diseases, effective treatment and necessary care, especially in high-risk pregnancies.

Regarding education, it is emphasized that this variable was undervalued by finding high levels of underreporting. It is a fact that the underreporting hampers the assessment of the problem's trend of maternal mortality and, consequently, the development of preventive and corrective actions for the situation. Although it is difficult to assess the information with reliability due to underreporting, it was found that maternal deaths by hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes were more prevalent in women with fewer years of study, which was observed8.

Thus, it can be noted a close relationship between maternal mortality and socioeconomic conditions, where the low education of women can negatively interfere in obtaining information about contraceptive methods and adherence to the guidelines provided in the prenatal period. Therefore, the guarantee of more schooling for the female population could be an important way to contribute in reducing unwanted pregnancies and the risk of maternal death.

Reporting to the variable color/race, in this study the predominant was brown when compared to others, which was expected due to the higher concentration of this color/race in the state. In Brazil, from 2000 to 2009, it was observed that 7,064 cases were reported in women of color/race brown, representing 42.74% of maternal deaths in Brazil7.

In 2005 in Rio Grande do Sul, the largest mortality ratio were also observed in women classified as brown, 129.7 per 100 thousand live births, corresponding to the data of the present study8.

According to the Ministry of Health, the causes of maternal death in black women are related to their biological predisposition to diseases such as hypertension, besides social factors and difficulty in accessing health services3.

Therefore, it should draw the attention of health professionals to social inequalities, sensitizing them and training them about the importance of health care quality, which needs to be ensured for all, including black women.

Regarding marital status, it was concluded that there was a predominance of death of unmarried women, mostly from hypertensive causes, entering into agreement with the study conducted in São Luís do Maranhão between the years 1999 and 2005, where it was observed a higher percentage (66.3%) in single women9.

The highest percentage of maternal mortality among unmarried women may reflect the early onset of sexual activity dissociated with marriage, lack of family planning or the disruption of the family. As is common the consequent breaking of ties between the mother and the baby's father and/or decision-making difficulties in discovering a pregnancy, contributing to the increase of maternal deaths in single mothers9.

In view of this, it is worth reflecting on marital relations, the contribution affective, emotional, social and financial support of women and encouragement to self-care to the mother by the baby's father and the family in order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. It is noteworthy that the presence of a partner and family during pregnancy and childbirth becomes an important protective factor in this process.

According to Table 2, it verifies the spatial pattern of Maternal Mortality in the State of Ceará, indicating the place of residence of the woman and the place where death occurred. This issue deserves attention, especially within the health planning, as it allows an analysis of the distribution, the geographic space, services and their clientele. The lack of information and analysis on the origin of service's customer difficult: the investigation of flows of people who require such services, connecting residence and place of care; identifying the networks established by such flows, and the delineation of catchment areas of public units based on their actual use10.

This table shows that most of the women resided in the countryside of the State of Ceará, however, many of these women died in the state capital. This fact leads us to infer that pregnant women sought specialized care in the capital and didn't achieved the desired success. A similar trend was observed in a study conducted in the state of Paraná, where it was found that 40% of women living in Curitiba and 60% in the countryside cities of this state, who were referred to the service of a reference hospital in that capital. This variable is considered relevant because of the strong relationship between place of residence and the social and cultural characteristics of individuals11.

Regarding the time of death from hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes, it was noted that most of them occurred during the postpartum period. This is corroborated by a study conducted in Santa Catarina, which showed that the majority of women who died due to a hypertensive cause were in the postpartum period12. However, in the South, a research shows that overall maternal mortality, including both causes presented, showed that 43.4% of the deaths occurred in pregnancy and childbirth2. Thus, we can infer that the pregnancy as is a period of physiological changes in the maternal organism so it can maintain the viability of the fetus, is the moment that inspires more care for these women. Thus, it should focus on health education strategies which has the aim to advise on disease prevention and encourage healthy lifestyle habits to avoid comorbidities that worsen your health. The ideal time to perform these activities is during the prenatal care, by allowing a group and individual approach about the living habits of the users. It is worth stressing that the investigation of the time of death showed that a considerable number of cases had been ignored or incongruous, setting up a problem of underreporting and undercount. This is a problem that directly affects the epidemiological analysis of mortality from specific causes in the panorama of the State of Ceará, since makes impossible to have the exact statement of these numbers. In a similar study, conducted in Paraná, evaluating Maternal Mortality between the years 2003-2005, it was noted that in 30.7% of the statements, these fields, for the period in which the death occurred, were filled incorrectly. In some cases, the record keeper dismissed maternal death, to tick no in the two fields in the DO to sort the timing of maternal death (pregnancy / childbirth / miscarriage or postpartum), when in fact this was maternal death13.

The leading cause of maternal death occurs due to complications caused by hypertension during pregnancy and childbirth, and consequences from hemorrhagic disorders that affect pregnant women between the second and third week of pregnancy and during the postpartum period, which characterizes the context of severe maternal morbidity14. Study conducted in São Paulo, which aimed to evaluate maternal deaths due to hypertension, obtained MMR of 13.2 / 100,000 live births15.This finding is consistent with the results here revealed, that each year showed higher numbers of hypertensive diseases than those related to bleeding, a fact that consolidated that one as the main cause of death among pregnant women. In research conducted in the city of Quixadá, to assess the main pathologies related to pregnant women attending prenatal visits showed that 86.6% of patients had hypertension16 .This information allows us to infer that measures should be taken for effective prevention and treatment of this disease in order to prevent maternal death. As for the hemorrhagic, they appear as the second most frequent cause of death linked to motherhood, highlighting abortion as a major trigger of this health problem15,17. Given its influence in the maternal mortality ratio by bleeding causes, it is noteworthy that the MMR by abortion, in western Santa Catarina, was 5,148.

Both diseases have variances that tend to increase over the years, however in 2007, they showed a different behavior when the MMR by hypertensive causes showed considerable decline and MMR by hemorrhagic causes was strongly increased. This phenomenon is due to the fact that it has been deployed in the state of Ceará, the form of Investigation of Death with Undefined Cause. Which uses data from the investigation records related to Primary Care Unit of the Family Health Program, Registry, Information Systems of Notifiable Diseases (SINAN), Institute of Forensic Medicine (IML), Service of Deaths Verification (SVO) and data from the National Health Foundation (FUNASA). When consulting all those databases referred to deaths was possible that there was an improvement of information on mortality in SIM, allowing greater reliability in recording and quantifying the cause of death18. Thus, it is believed that during the year 2007 maternal deaths were best identified, which justifies the change in patterns of RMM's presented. However, in consecutive years from 2008 to 2010, it was observed that the numbers returned to oscillate with a tendency to increase. It is believed that this may be explained by errors that occur during the filling of the death certificate (DO). Study on the Paraná undercounts and underreporting the number of maternal deaths, says the incorrect filling of DO implies on the analysis result to obtain and count the causa mortis, which directly affects the presentation of the epidemiological picture of maternal deaths, resulting in difficult strategic actions of public policies to eradicate general and specific maternal mortality13. Such underreporting and undercounts are common in other diseases, it is important to conduct further studies that demonstrate the reasons for the failure19,20.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Maternal mortality by hypertensive and hemorrhagic causes are in the Brazilian and global framework as public health problems that affect thousands of people. Despite the existence of public policies aimed at reducing the incidence of these diseases, this study allows us to say that they need to be the focus of attention of health professionals to carriers as well as be vigilant in order to prevent its incidence.

Finally, it is clear that maternal mortality in Ceará for such causes still has high coefficients. Therefore, it is necessary to reinforce public policies of assistance to women throughout the pregnancy cycle, as well as ensuring proper treatment for those who are suffering from such diseases that endanger her life. Thus, it is expected to be possible having a significant decrease in rates of obstetric death until they reach the numbers recommended by WHO, and public health in Brazil to be known as effective and of great quality for all Brazilians.

One limitation of this study is the underreported some information contained in the notification form of maternal mortality which made hard to build a more comprehensive profile of this population. Thus, we recommend that the professional acting directly on surveillance to be careful to complete each item of the questionnaire.

REFERENCES

1.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Guia de vigilância epidemiológica do óbito materno. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2009.

2.Sombrio SN, Simões PW, Medeiros LR, Silva FR, Silva BR, Rosa MI, Farias BF. Razão de mortalidade materna na região sul do Brasil no período de 1996 a 2005. ACM Arq Catarin Med. 2011; 40(3): 56-62.

3.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Políticas de Saúde. Área Técnica de Saúde da Mulher. Manual dos Comitês de Mortalidade Materna. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2007.

4.Leite RMB, Araújo TVB, Albuquerque RM, Andrade ARS, Duarte Neto PJ. Fatores de risco para mortalidade materna em área urbana do Nordeste do Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2011; 27(10): 1977-85.

5.Ministério da Saúde (Br). A declaração de óbito: documento necessário e importante. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2009.

6.Marinho ACN, Paes NA. Mortalidade materna no estado da Paraíba: associação entre variáveis. Rev esc enferm USP. 2010; 44: 732-8.

7.Bordignon LFM. Mortalidade materna no Brasil: uma realidade que precisa melhorar. Rev baiana saúde pública. 2012; 36: 527-38.

8.Carreno I, Bonilha ALL, Costa JSD. Perfil epidemiológico das mortes maternas ocorridas no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: 2004-2007. Rev bras epidemiol. 2012; 15: 396-406.

9.Trabulsi ALS, Mochel EG, Chein MBC, Brito LMO, Santos AM, Ribeiro IGS, Pinheiro GL. Mortalidade materna em São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil: 1999-2005. Revista do Hospital Universitário/UFMA. 2009; 10(2): 62-8.

10.Melo ECP, Knupp VMAO. Mortalidade materna no Município do Rio de Janeiro: magnitude e distribuição. Esc Anna Nery. 2008; 12: 773-9.

11.Kefler K, Souza SRRK, Wall ML, Martins M, Moreira, SD. Características sociodemográficas e mortalidade materna em um hospital de referência na cidade de Curitiba-Paraná. Cogitare Enferm. 2010; 15: 500-5.

12.Saviato B, Knobel R, Moraes CA, Tonon D. A Morte materna por hipertensão no Estado de Santa Catarina. ACM arq catarin med. 2008. 37(4): 16-9.

13.Soares VMN, Azevedo EMM, Watanabe TL. Subnotificação da mortalidade materna no Estado do Paraná, Brasil: 1991-2005. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008; 24: 2418-26.

14.Luz AG, Tiago DB, Silva JCG, Amaral E. Morbidade materna grave em um hospital universitário de referência municipal em Campinas, Estado de São Paulo. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2008; 30: 281-6.

15.Vega CEP, Kahhale S, Zugaib M. Maternal mortality dueto arterial hypertension in São Paulo City (1995-1999). Clinics. 2007; 62: 679-84.

16.Barros MEO, Lima LHO, Oliveira EKB. Prenatal care in the city of quixadá: a descriptive study. Online braz j nurs. 2012; 11: 319-30.

17.Souza ML, Ferreira LAP, Burgardt D, Monticelli M, Bub MBC. Mortalidade por aborto no Estado de Santa Catarina - 1996 a 2005. Esc Anna Nery. 2008; 12: 735-40.

18.Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise de Situação em Saúde. Manual para investigação do óbito com causa mal definida. Brasília (DF): Editora MS; 2009.

19.Abreu AMM, Jomar RT, Thomaz RGF, Guimarães RM, Lima JMB, Figueirò RFS. Impacto da Lei seca na mortalidade por acidentes de trânsito. Rev enferm UERJ. 2012; 20: 21-6.

20.Alves H, Domingos LMG. Manejo de eventos adversos pós-vacinação pela equipe de enfermagem: desafios para o cuidado. Rev enferm UERJ. 2013; [citado em 12 mar 2014] 21: 502-7. Disponível em: http://www.facenf.uerj.br/revista/v21n4/v21n4a14.pdf.