RESEARCH ARTICLES

Medication reconciliation at a university hospital

Fernanda FrizonI, Andreia Hirt SantosII, Luciane de Fátima CaldeiraIII, Poliana Vieira da Silva MenolliIV

IResident Pharmacist at the Hospital Universitário do Oeste do Paraná (University Hospital of West Paraná), Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (State University of West Paraná), Cascavel, Paraná, Brazil. E-mail: nandafrizon@hotmail.com.ABSTRACT: Prescribing and administration errors account for more than 75% of medication errors in hospitals. Medication reconciliation provides an alternative for reducing this occurrence. In Brazil, research on medication reconciliation is in its incipiency; thus, this study aimed to present a profile of patients and the results of medication reconciliation at a hospital. This was a prospective cross-sectional study conducted of the West of Paraná, Brazil, in 2011, where 58 patients were interviewed: 27 (46.5%) had at least one chronic disease, 24 (41.3%) were using drugs at home, 15 (62.5%) of whom showed at least one type of medication error, with errors most involving the antihypertensive pharmacological group, 24 times (32%). Of 61 discrepancies found, 49 (80%) were not justified. Pharmaceutical interventions were accepted in 87% cases. Patients who underwent the process of medication reconciliation were aged above 50 years and were using more than 3 continuous medications at home.

Keywords: Medication reconciliation; medication errors; patient safety; drug prescription.

INTRODUCTION

The Medication errors, considering prescription more administration, account for over 75% of drug-related errors in the hospital, and each patient experiences at least one medication error per day in a hospital in the United States of America (USA)1. Patient safety is the focus and priority of the work of governments, organizations, and health institutions aiming to decrease the risks and costs related health services use2-5.

In Brazil, studies on implanting medication reconciliation into existing health services are still incipient6. More such studies are needed to ensure the adequacy of this important process, which contributes to the prevention of medication errors and decreases hospital readmissions7,8, for the reality of Brazilian medical institutions.

This article aimed to find out the profile of patients admitted to a hospitalization unit at a university hospital, and reports the results of the medication reconciliations performed during their admission to the unit.

LITERATURA REVIEW

Medication reconciliation is defined as the process of obtaining a complete, precise, and updated list of medications that each patient uses at home (including the name, dose, frequency and form of administration) and compared with the medical prescriptions made during admission, transfer, outpatient consultations with other doctors, and hospital discharge. This list is used to improve medication use across all of the patient’s transition points in the health system and primarily aims to decrease the occurrence of errors with medications when patients change their level of health care assistance1,9.

The reconciliation was proposed to avoid or minimize errors in transcription, omission, therapeutic duplication, and drug interactions. When discrepancies in medical orders are identified, medical assistants are informed and, if necessary, the prescriptions are corrected and documented10. The process includes double-checking the medications being used; an interview with the patient, the family, or their caretakers; comparison with the medical orders; and a case discussion with the clinical team11. The patients or their caretakers have a fundamental role in this process, supplying information to prepare a list of medications that are used. For this assessment, it is necessary to inform the patient, family and/or caretaker about the procedure involved and obtain authorization to do so12.

Medication reconciliation is an important tool that systematizes procedures aimed at making the therapy of patients who pass through transition points during their assistance more compatible. Thus, The Joint Commission, the largest accreditation agency in the United States that acts in more than 40 countries, along with other organizations that aim to promote patient safety within the health services4,9,13, recognizes the need to develop protocols for preparing complete lists of medications that patients use frequently, acquired with or without a medical prescription, placing medication reconciliation on the list of national objectives for patient safety in order for hospitals in the USA to gain accreditation.

To implant medication reconciliation into health care services, various steps, with an emphasis on multidisciplinary teams that include nurses, pharmacists, and doctors, are necessary14.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)10 recommends that medication reconciliation be done in three stages. The first stage involves verification, which consists of collection and elaboration of a list of medications that the patient used before being admitted, their transfer or discharge; the second is confirmation, a stage that aims at assuring that the medications and the prescribed doses are appropriate for the patient; and the third stage is the reconciliation, which consists of identifying discrepancies between the prescribed medications at each level of health care or transition point, in the documentation of communications made to the prescriber and the correction of prescriptions along with the doctor.

Data from previous studies10,15 demonstrate that reconciliation results in greater safety for patients by means of identification, investigation and correction of errors in medication, and that such a practice is able to attenuate the readmission of the accompanied patients.

METHODOLOGY

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted at the Hospital Universitário do Oeste do Paraná (University Hospital of West Paraná) (HUOP), in the city of Cascavel, in Western Paraná, Brazil, in a hospitalization unit that includes neurology, orthopedics and vascular clinics. The unit has 26 hospital beds, all serviced by the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde or SUS). All of the patients hospitalized at the unit coming from outside the institution from 12 September to 12 October 2011 were a part of the intentional sample. The data were collected daily, by means of an interview and chart analysis, at the time of hospitalization, with the objective of performing medication reconciliation at the time when patients are admitted. Patients who were transferred to other hospitalization units or who had stayed for more than 48 hours in first aid at the hospital were not included, as these procedures were considered as transfers between units.

Standardized instruments for medication reconciliation were used for collecting data, based on the guidelines issued by The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2007)10 and adapted for the HUOP by means of a pilot study.

The study consisted of three stages:

Patient medical history wasobtained, as well as information on when the terms of consent for research were explained and data about the presence of chronic illnesses were extracted, patient history of allergies, and whether patients continuously used medications before being hospitalized. Medication reconciliation was the time when information was collected about the medications brought in by the patient and those that they reported using before being hospitalized, and when comparisons were made between the hospital’s medical prescription and information on the medications brought by the patient and those used sporadically, such as teas, stimulants, appetite suppressants, and food supplements.

The main medications involved in medication reconciliation problems were identified, as well as their characteristics, and discrepancies were then classified as those associated with either previously used medication or justified/unjustified medical prescriptions16.

Justified discrepancies were when a medication prescription was justified by the clinical situation; medical decisions to not prescribe a medication or alter the dosage, frequency or form of administration according to the protocols; and therapeutic substitutions according to medication standards of the hospital.

Unjustified discrepancies were when there was an omission of a necessary medication; addition of an unjustified medication for the patient’s clinical situation; substitution without clinical justification or for reasons of product availability; a difference in the dosage, form of administration, frequency, time or method of administration; and duplication or drug interaction.

The third stage involved the pharmaceutical intervention, during which the prescribing doctor was informed in writing about the discrepancies found in the medication reconciliation of the admitted patients. Later, the chart for each patient was checked to see if the intervention had been accepted by the doctor. A standard of 72 hours from the registration of interventions on the chart was set to determine if doctors had accepted these interventions. If doctors did not accept these interventions within this period of time, the interventions were considered not accepted.

The data were tabulated and analyzed with the Epi Data and Excel for Windows programs, by means of averages and frequencies.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Regulations for Research on Human Beings, according to Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Health Advisory17, and was submitted to the Research and Ethics Committee (CEP) at the Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (State University of West Paraná), with favorable opinion number 148/2011-CEP.

RESULTS

In the first stage, the Medical History, 58 patients were interviewed. Of these, 34 (58.6%) were male. The average age was 52 years (range: 17–92 years) and the average duration of hospitalization was 6 days. The clinic that attended most patients was orthopedics 34 (58.6%), followed by neurology 13 (22.4%) and vascular 11 (18.9%).

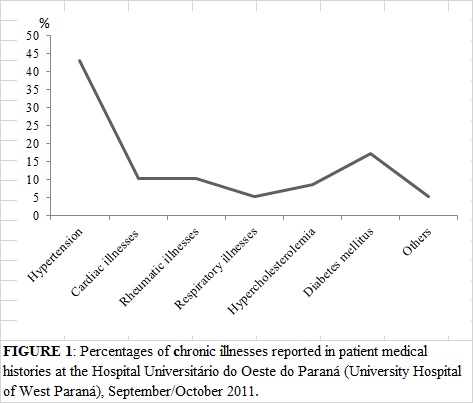

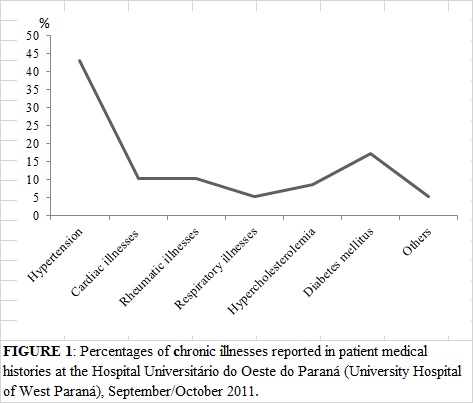

Regarding the presence of chronic illnesses, 27 (46.5%) of the patients reported having at least one chronic illness; arterial hypertension and Diabetes Mellitus were the diseases most cited, with 25 (43.1%) and 10 (17.2%) cases each. The report of illnesses cited by the patients is presented in Figure 1.

Regarding hypersensitivity to medications, 10 (17.2%) of the patients reported already having had allergic reactions, and the most cited medications were dipyrone 3 (30%) and penicillin 2 (20%) times.

Of the 58 patients interviewed, 24 (41.3%) reported having use medications at home, and only in this patients were applied the medication reconciliation. Thirty-five medications in the reconciliation were cited by the patients as having been used at home for previous treatment of other pathologies, and only 9 (37.5%) of the patients brought their medications to the hospital. The average age of these patients was 70 years (49–92), and they used, on average, 3.2 (1–6) medications continuously.

Of the medications cited 28 (80%) were standardized at the hospital. Of these, 1 (2.8%) showed an expired date of validity. In this case, pharmaceutical guidance was given on the correct storage of medication and the importance of not using expired medications.

All patients were also informed that there was no need for them to use their own medication since, after contact with their attending physician, the patient would use the medication from the hospital during the hospitalization period if necessary.

Of the 24 patients who needed medication reconciliation, 15 (62.5%) showed at least one type of error related to their medication, making pharmaceutical intervention necessary. Sixty-one discrepancies were detected between previous medications used and hospital prescriptions, of which 41 (67.2%) were related to the omission of medications and 18 (29.5%), to unnecessary additional medications. On average, there were 4.6 discrepancies per patient. Of the discrepancies detected, 49 (80%) were classified as being unjustified, since, after the intervention, the medications were included in the prescription by the doctor, while 12 (20%) were classified as being justified. Among the justified discrepancies, 5 (41.6%) were due to the metformin use, which, according to the attending physician´s orientation, was not suitable for the hospital environment. The profile of the discrepancies found is shown in Figure 2.

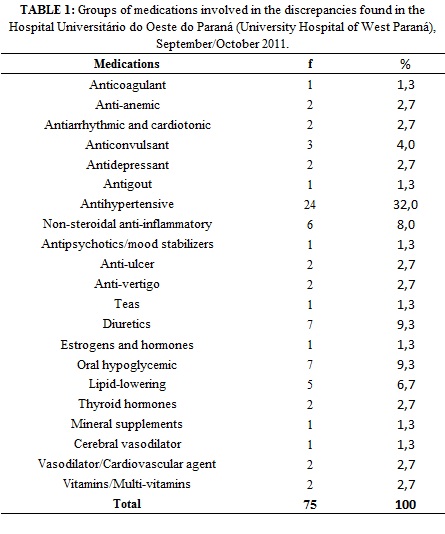

The pharmacological groups most involved in the discrepancies were antihypertensives 24 (32%) times, diuretics and oral hypoglycemics 7 (9.3%) times each, and lipid-lowering medicines - 5 (6.6%) times. The medications involved in discrepancies with hospital medical prescriptions are shown in Table I.

There were 15 pharmaceutical interventions conducted that were accepted in 13 (87%) cases. In the cases where pharmaceutical interventions were not accepted, it was not possible to contact the doctor responsible for the prescription and the doctor did not accept the pharmaceutical intervention written on the chart.

I

DISCUSSION

The HUOP is a general hospital; however, the data obtained in the present study reflect only the reality of the unit studied (orthopedics, neurology, and vascular). The predominance of male patients is justified because the hospital is the reference in attending to traumas by the SUS which are more common in males18,19 and differ from the profile of patients hospitalized in the United Health System, the majority of whom are female20.

The variation in the ages of patients, 17–92 years, also reflects the characteristic of the unit, which receives patients with neurological and vascular problems of advanced age and young patients who are recuperating from traumas (after orthopedic surgeries or transfer from intensive care units). However, the average age of the patients who needed medication reconciliation was higher than the general average; furthermore, medication reconciliation was related to continuous medication use for chronic illnesses, which was more prevalent from age 40 and in those who needed to use various medications for the control and treatment of their conditions21-23.

Among the chronic illnesses most cited by the patients were systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus are the main risk factors for cardiovascular illnesses in the population, and their consequences are important causes of hospitalizations in SUS22. Common problems associated with the worsening of these conditions constitute thrombus-embolic problems, vascular cerebral accidents, amputations and revascularizations in diabetic neuropathy, and renal problems,24,25 all of which are commonly attended to in the unit for vascular, neurological and orthopedic treatment. A Spanish study found similar values for diabetes and lower values for the frequency of arterial hypertension in hospitalized orthopedic patients16.

Chronic illnesses, by presenting the need for treatment with multiple medications, represent a challenge for medication reconciliation26. During hospitalization, many patients do not report, for having forgotten or even due to embarrassment, the illnesses that they have and all the treatments they use. Beyond medications, many teas and food supplements are also used in treating chronic illnesses, which could be omitted by patients who frequently do not think of these types of treatment as being relevant to pharmacotherapy.

At the time of hospitalization, a lack of complete information could lead to an interruption or inadequacy in the medication therapy, or result in the failure to detect problems related to medications as a cause for hospital admission, capable of causing damage to the patient26. The difficulties that patients have in understanding the therapy chosen by the outpatient doctor and the lack of communication with patients while preparing their medical history at the time of hospitalization could lead to prescription errors during hospital stays27.

This study found that 62.5% of the patients interviewed showed at least one error between the medications used at home and hospital prescriptions. Prescription errors are common for adult patients at the time of admission to hospital units, and at least 60% of patients hospitalized will have at least one discrepancy in their admission history10,26,27,28. The lack of communication about medical orders upon admitting the patient and at other transition points in the health unit is responsible for more than 50% of all errors in medication that occur in hospitals27.

In the HUOP prescriptions, there were 61 discrepancies identified, with the error of omitting medications being the most frequent, which is similar to that found in other studies11,26,29. The discrepancies between medications that patients use at home before hospitalization and those listed at the time of admission can vary 30–70%. The occurrence of a significant number of errors at admission could be caused by admissions occurring on the weekends or at night, when patients often report the use of eight or more medications, or when there are service overloads26.

Unjustified discrepancies, which were found in the majority (80%) of the patients studied, are also most commonly observed in other studies11,26. Such events are considered medication errors and could have clinical consequences with the potential to cause harm or harm the patients themselves28.

The groups of medications most frequently detected in this study were primarily those involved in discrepancies between hospital prescriptions and medications used at home, which was also observed in other hospitals10,26. Only one study showed vitamins and electrolytes as the main class29.

Medication reconciliation has the ability to intercept and correct 75% of clinically important discrepancies before harm is done to the patient28. In this study, even without evaluating the capacity of discrepancies detected to cause harm to patients, pharmaceutical interventions were widely accepted (87%) by doctors and applied. Similar results were observed in two studies— 71.1%30 and 88.7%10—and were lower in two others—40%29 and 46%28.

Dialogue and decisions of a multidisciplinary team are fundamental for medication reconciliation and the reduction of potential damage to patients. Pharmacists, doctors, and nursing staff are indispensable in the selection, prescription, and administration of medications, and in monitoring and patient education during hospitalizations.

In Brazil, the roles of the medical team and nurses in the multi-professional teams are clear; however, the inclusion of other professionals is still in the works. One should consider that pharmacists are especially suited to the task of obtaining more complete histories of medicines and reconciling discrepancies due to their training, experience, familiarity with, and knowledge about the medications27,31. To guarantee the safety of patients, it is necessary to implement systemic strategies to improve the performance of this service, and this aim needs to be institutional and individual for each professional involved32.

Other results of medication reconciliation, not evaluated in this study, but relevant and reported by other authors, are cost reduction and a decrease in hospital readmissions7,8.

Problems related to medications entail complaints associated with negligence, which could generate legal problems for the health institutions involved. To sum up the general costs of problems with medications, it is crucial to note that such problems are considered to be the greatest source of hospital expenses, greater than any other type of injury caused by procedures, reaching US$47 billion annually, with costs related to patient morbidity and mortality33.

Besides decreasing costs due to complaints about negligence, reductions of 16%6 and 30%7 have also been found in the rates of re-hospitalization of patients who go through medication reconciliation while being hospitalized. A systematic revision published in 2013 did not find evidence that medication reconciliation decreased the mortality of patients being monitored, but found a decrease of 35% in attendance of these patients by the emergency sector15,34. Medication reconciliation could improve the care provided to patients in transitions between levels of health care34.

CONCLUSION

Patients attended to in the unit were, for the most part, men, with ages at both extremes of adult life, youth recuperating from traumas, and adults over 50. Further, the clinic that most received patients was the orthopedics clinic. Practically half of the patients reported having a chronic illness and continuously used medications. These patients underwent the medication reconciliation process. Medication reconciliation found medication errors among more than half of the patients being monitored and was able to resolve discrepancies between hospital prescriptions and the home use of medications by the patients attended, with the medical team showing good acceptance of the interventions employed.

REFERENCES

1. Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman JL, Cronenwett LR editors. Preventing medication errors. Quality chasm series. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2007.

2. Silva LD. Segurança e qualidade nos hospitais brasileiros. Rev enferm UERJ. 2013; 21:425-6.

3. Souza RFF, Silva LD. Estudo exploratório acerca da segurança dos pacientes em hospitais do Rio de Janeiro. Rev enferm UERJ. 2014; 22:22-8.

4. World Health Organization. Assuring medication accuracy at transitions in care. Standard operating protocol fact sheet. [cited in 2014 Apr 20] Available in: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/ps_medication_reconciliation_fs_2010_en.pdf

5. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Portaria nº 529, de 1º de abril de 2013. Institui o Programa Nacional de Segurança do Paciente. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2013.

6. Anacleto TA, Rosa MB, Neiva HM, Martins MAP. Erros de medicação. Pharmacia Brasileira. 2010; 74:1–24.

7. Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H, et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:894-900.

8. Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfield K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The Care Transitions Intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1232-7.

9. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in medication reconciliation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2013; 70:453–6.

10. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 5 Million Lives Campaign. How-to guide: prevent adverse drug events (medication reconciliation). [cited in 2014 Mar 20] Available in:

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventAdverseDrugEvents.aspx

11. Manno MS, Hayes DD. Beste-practice interventions: how medication reconciliation saves lives. Nursing. 2006; 36:63-4.

12. Pronovost P, Weast B, Schwarz M, Wyskiel RM, Prow D, Milanovich SN, et al. Medication reconciliation: a practical tool to reduce the risk of medication errors. J Crit Care. 2003; 18:201-5.

13. The Joint Comission. Hospital Accreditation Program 2009. Chapter : National Patient Safety Goals. [cited in 2014 Mar 20] Available in: https://www.unchealthcare.org/site/Nursing/servicelines/aircare/additionaldocuments/2009npsg

14. Ketchum K, Grass CA, Padwojski A. Medication reconciliation: verifying medication orders and clarifying discrepancies should be standard practice. Am J Nurs. 2005; 105:78-85.

15. Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 [cited in 2014 Mar 20] Available in: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008986.pub2/pdf

16. Moriel MC, Pardo J, Catalá RM, Segura M. Estudio prospectivo de conciliación de medicación en pacientes de traumatología. Farm Hosp. 2008; 32:65-70.

17. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Resolução nº 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Brasília (DF): CNS; 2012.

18. Freitas IA, Nóra EA. Serviço de atendimento movel de urgência: perfil epidemiológico dos acidentes de trânsito com vitimas motociclistas. Revista Enfermagem Integrada. 2012; 5:1008-17.

19. Cabral APS, Souza WV, Lima MLC. Serviço de atendimento móvel de urgência : um observatório dos acidentes de transportes terrestre em nível local. Rev Bras epidemiol. 2011; 14:3-14.

20. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Datasus - Sistema de Informações Hospitalares do SUS - SIH/SUS[site de internet]. Internações por sexo segundo faixa etária, 2002. [cited in 2014 mar 2014] Available in: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?idb2003/d13.def

21. Pinelli LAP, Mantadon AAB, Boschi A, Fais LMG. Prevalência de doenças crônicas em pacientes geriátricos. Rev odonto ciênc. 2005; 20:69-74.

22. Ministério da Saúde (Br). Secretaria de Políticas de Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estrategicas. Plano de reorganização da atenção à hipertensão arterial e ao diabetes mellitus: hipertensão arterial e diabetes mellitus. Brasilia (DF): Ministério da Saúde; 2001.

23. Lyra Júnior DP, Amaral RT, Veiga EV, Cárnio EC, Nogueira MS, Pelá IR. A farmacoterapia no idoso: revisao sobre a abordagem multiprofissional no controle da hipertensao arterial sistêmica. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2006; 14:435-41.

24. Rio Grande do Sul. Conselho Estadual do Idoso. Os idosos do Rio Grande do Sul: estudo multidimensional de suas condiçoes de vida: relatório de pesquisa. Porto Alegre (RS); 1997.

25. Lerário AC. Peculiaridades do tratamento no idoso com diabetes. In: Albuquerque R, Netto AP, editores. Diabetes na prática clínica. Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes; 2011. p.221.

26. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, Tam V, Shadowitz S, Juurlink DN, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:424-9.

27. Galvin M, Jago-Byrne MC, Fitzsimons M, Grimes T. Clinical pharmacist's contribution to medication reconciliation on admission to hospital in Ireland. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013; 35:14–21.

28. Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006; 15:122-6.

29. Lessard S, Deyoung J, Vazzana N. Medication discrepancies affecting senior patients at hospital admission. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006; 63:740-3.

30. Gleason KM, Groszek JM, Sullivan C, Rooney D, Barnard C, Noskin GA. Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004; 61:1689-95.

31. Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, Wahlstrom SA, Brown BA, Tarvin E, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:565-71.

32. Silva LD, Carvalho MF. Revisão integrativa da produção científica de enfermeiros acerca de erros com medicamentos. Rev enferm UERJ. 2013; 20:519-25.

33. Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, Burdick E, Laird N, Petersen LA, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1997; 277:307-11.

34. Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M, Shojania KG. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158:397-403.